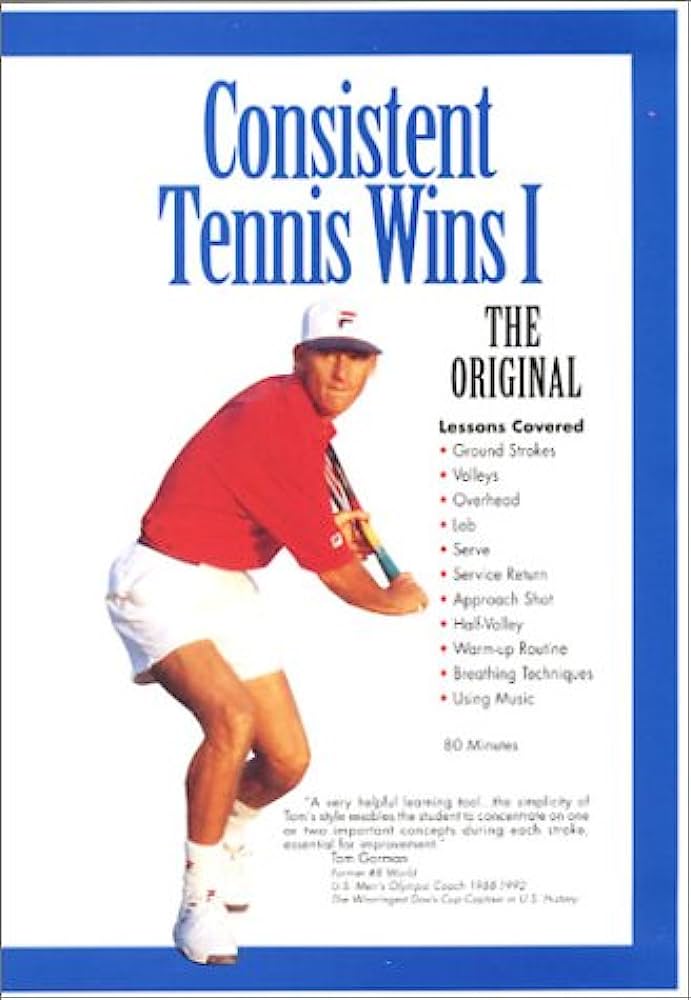

Image credit — and DVD source — here: https://www.amazon.com/Consistent-Tennis-Wins-Tom-Avery/dp/B00008IODZ)

Investing and tennis have a humbling similarity: For most people, more improvement will come from removal of mistakes than from doing something aggressive or proactive.

Play a consistent game and wait for your opponent (the market) to mess up.

Humans will always mess up.

Humanity is constantly creating economic value, so the economy isn’t a zero-sum game. Ditto for a long-term investment in an overall market index fund to capture that broad growth.

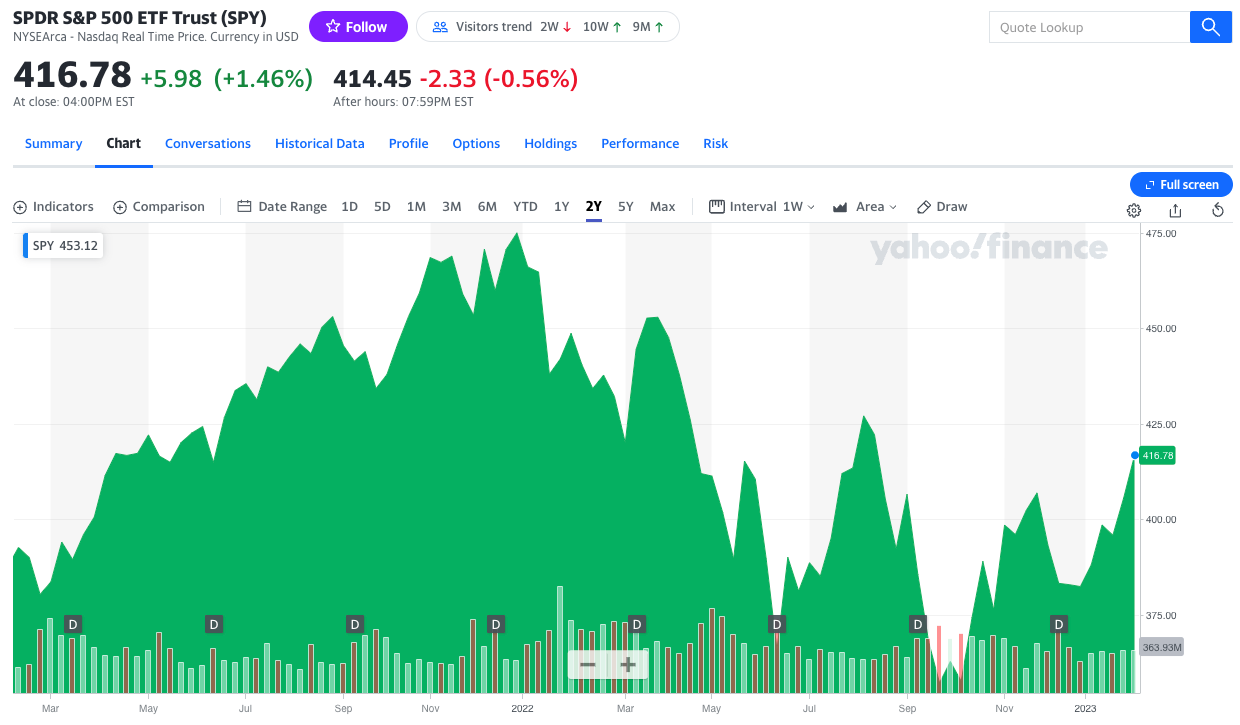

But to beat the market – and just matching the market would be a win for most people; in 2021, for instance, the S&P 500 rose 29%, but the average investor gained just 18% – you need to capitalize on the market’s mistakes.

The good news? The people who make up the market are loaded with cognitive and emotional biases, blind spots, and the like.

The bad news? You are, too.

If you’ve been playing poker for half an hour and you still don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.

Warren Buffett

Our own worst enemies

Academic research has uncovered multiple biases that cause us to underperform.

Here are five of the many mistakes you may be making:

- You’re overtrading. Pablo Picasso said “Action is the foundational key to all success.” Picasso was right about most of life, but a social science like investing is the exception.

- In Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors, professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean found that from 1991 to 1996, the S&P 500 rose 18% annually, yet households that traded the most earned just 11% per year.

- Dalbar Research found that over a 20-year period when stocks rose 7.5% annually, the average investors earned just 2.9% annually.

- Barber and Odean again found that more than 80% of Taiwanese day traders lose money.

- To be fair, as these guys point out, everybody doesn’t overtrade all the time, in the same way, and for the same reasons.

But, mostly, we overtrade.

- You’re holding losers too long. Supposedly, the pain of a loss is something like 2-3 times as strong as the pleasure of an equivalent gain. I say supposedly because the degree is debated. But in Are Investors Reluctant to Realize Their Losses? (hint: yes), Terrance Odean found that investors show a strong preference for realizing gains relative to losses. Embarrassingly, Odean found that when investors finally do sell a stock and buy something else, the replacement stock underperforms the sold stock by nearly 9 percentage points over the next two years.

- You’re chasing winners: Bloomberg reported that fund investors put more new money into equity funds in 2021 than in the previous 19 years combined. Is it a coincidence that 2021 marked the top of a 13-year bull market? I think not.

(Image: Yahoo! Finance)

- You’re anchoring on price paid. In Initiating Salary Discussions With an Extreme Request, Todd Thorsteinson from the University of Idaho found that when a job seeker whose market price was $29,000 yearly (it’s an old study) started the salary discussion by joking: “I’d like $100,000, but really, I’m just looking for something that’s fair,” he or she received a higher offer. The most common investing version of anchoring would be fixating on the price you paid for a stock that’s declined and become unattractive, and either resisting selling because the stock “feels” like it’s worth the price paid, or because you want to wait to break even before selling, as if the stock remembers what price you specifically paid and feels a sense of obligation to return there.

- You’re following the herd (FOMO). This is dangerous because it works sometimes. And as we saw during the recent crypto and meme stock bubble, it can work long enough to make real people real money. Economics is a social science that depends on group buy-in. As Game Stop and AMC shareholders showed, it is possible to create your own reality with enough buy-in. But it’s hard for that reality to last a long time if there aren’t economic underpinnings attached.

These biases are not bad things at all – for cavemen. They’re mental shortcuts that helped our ancestors survive.

What can you do about these biases? Think like an alcoholic

Don’t expect to remove these biases, at least as long as you want to have a human brain.

Rather, investors would be wise to take a page from the Alcoholics Anonymous playbook: Own up to the fact that you’re wired with innate tendencies that pull you astray. And – importantly – acknowledge that you need external guardrails because your feelings can’t be fully trusted to keep you on track.

What guardrails exactly?

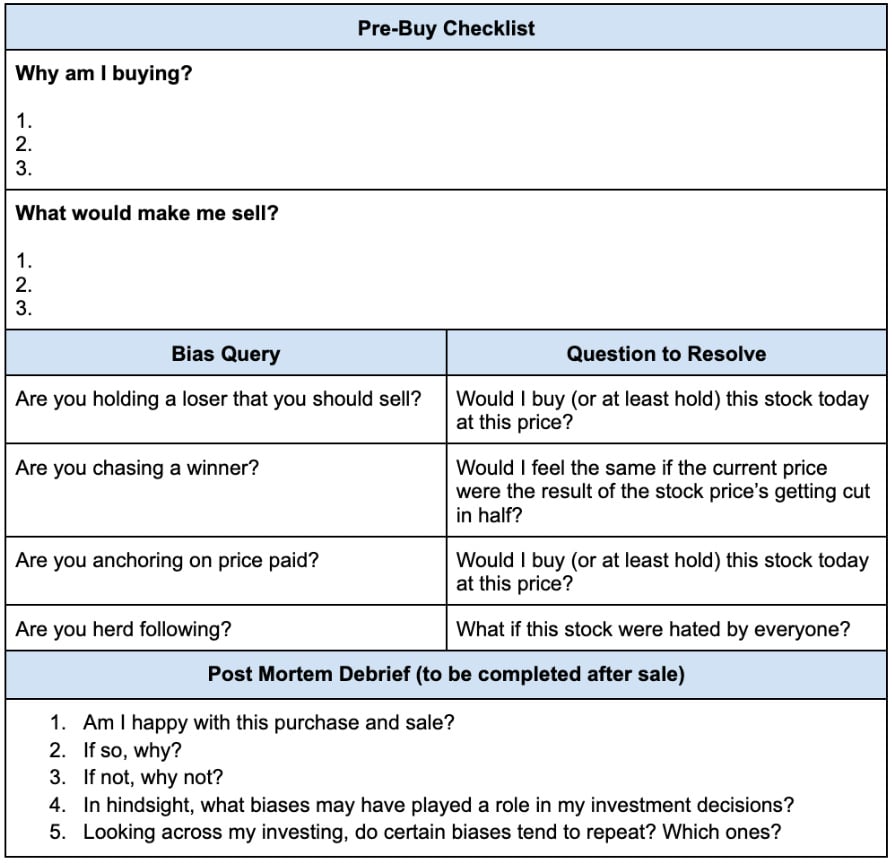

I used to simply advocate writing down a quick summary of your reasons for buying each stock you own. You should do that, but it’s not enough.

Here’s a semi-helpful checklist. It won’t stop full-blown bias. Nothing will. But it keeps bias in mind and might help you flag a lesser case of it.

Again, if you’re drunk with passion for a stock, it’s too late: The biased part of your mind, when revved up, is going to find a way to convince the unbiased part to let it have the keys. For that trade, expect to become sacrificial fodder for the future profits of a more rational investor.

We all pay it forward in investing now and then. But hopefully less frequently after you’ve read this and applied these principles.

Stay consistent and let the market make mistakes. That’s how the pros win.

This post was sponsored by BBAE, a $0-commission broker. BBAE wants you to grow your wealth – and has the resources to help. You can learn more by clicking here.