So you’ve decided that you want income. Maybe you’re approaching that time in your life when you’re ready to start living off your nest egg. Maybe you’re not there yet – but you’ve had enough “fun” in the risky tech stocks that rose to the moon over the past 14 years… until they didn’t.

Whatever your reason, you probably appreciate the risk reduction of income investing: Unlike here-today-and-maybe-gone-tomorrow capital gains, once you get paid cash, there’s no taking it back.

Let’s look at some various ways you can invest for income.

How to invest for income

Dividend stocks

Confession: I’m biased here. I’m biased because for 10 years I ran an investment research service called Motley Fool Income Investor (and for 5 years picked dividend stocks for their London office). I was blessed to have good performance, and recently wrote a report called 5 Secrets to Dividend Investing that you can get free of charge here.

Anyway, in addition to the report, I recently penned a comprehensive article on dividend stocks that you can read here, so I’ll be brief in this piece, but broadly speaking, dividend stocks themselves offer a wide range of options for income-seeking investors, from high-yielding real estate investment trusts (REITs) and master limited partnerships (MLPs)

If you’re a US investor, you will pay US tax on dividends (assuming you’re holding the stocks that pay them in a taxable account). This is generally at – you guessed it – the dividend tax rate (see my article for more on this), but for REITs it’s ordinary income; this is why some people hold REITs in an IRA or other tax-deferred account.

For MLPs, which require you to lose your conscious mind to understand, your share of net income is taxed at ordinary income rates, although the actual cash you receive is generally considered a tax-free return of capital – so you tend to not pay tax on the cash you receive, but instead pay tax on a share of income that you don’t receive.

(By the way: Don’t be scared by MLPs. Just avoid them if you’re a beginner.)

“Dividend stocks” is a wonderfully huge category that runs the gamut from barely-into-”income”-category 2% yielders to companies paying 10% or more (be careful with them). WIth dividend stocks, you can diversify across sectors, industry, geography, and financial factors – and because they’re stocks, they’re easy and cheap to buy (in fact, free if you use BBAE).

Dividend stocks tend to be a mainstay of income investing in the US for the reasons above.

Funds of dividend stocks (and other income generators)

In an era when we have more mutual funds (~7,400) than stocks (~6,000) in the US and a smaller-but-still-hefty number of ETFs (~3,000), it’s no surprise dividend-focused mutual funds and ETF abound. There are funds for almost everything – including many of the other income categories below. ETFs tend to be more tax-efficient than mutual funds, and tend to structure their payouts quarterly, whereas mutual funds may pay out at less specific intervals. But there are great options in both categories – just read the details and watch the fees.

Bonds

Bonds were dividend stocks before there were dividend stocks. Or, really, dividends arose as the equity market’s attempt to copy bonds – at least their regular payments, which investors of that era were familiar with.

Even though you “buy” bonds, they’re technically loans – loans to a company (corporate bonds) to a country (sovereign bonds) or to a state or municipality (“muni” bonds). Bonds are actually little contracts (indentures, they’re called), each with its own terms, so although the bond market is larger than the stock market, there’s less standardization: A stock is a stock, but bonds can differ in yield and cadence of payments, maturity, pecking order in the event of a bankruptcy and whether the investment is collateralized or not, and probably few other details that I’m forgetting at the moment. (For those fearful of individual-bond complexity, scores of bond mutual funds and ETFs will happily take your investment.)

Corporate bond payments are taxed at ordinary income rates; US Treasury bonds are taxable on the federal level, but not on the state level (a perk if you live in high-tax state like California or New York, but less thrilling if you live in, say, Alaska or Florida, which don’t levy a state income tax), whereas most muni bonds are exempt from federal and state taxes in the state that issued them.

Note that this is not a comprehensive bond tax explanation, and other taxes (AMT, capital gains, etc.) so don’t you dare think I’m giving tax advice or even tax suggestions: Read up yourself, and/or consult a tax professional before you act on anything.

The real point of bonds is the coupon payment, which is generally fixed for some number of years; at the end, investors get their final coupon payment plus a return of their original principal (often $1,000 per bond, which is the amount you loaned out at the beginning). Another selling “point” is that bonds are often said to move inversely relative to stocks, but this is actually not reliably true.

Back to that fixed coupon payment.

One risk is that you don’t get it. Companies, countries, and municipalities default from time to time. Bond credit rating agencies – Moody’s, Fitch, and S&P in the US – try to assess default risk, though they’re sometimes criticized for being understaffed and slow to bake in current happenings.

Another risk is that the price of your bond goes down. If you’re planning to hold the bond to maturity, part of your brain doesn’t care about this – the same part that doesn’t care what happens to the value of your home as long as you’re living in it — but another part that notices opportunity cost might.

Bond prices may decline because the borrower becomes more sketchy, or because new bonds pay higher interest rates. In fact, bond investing is largely about interest rate awareness, and professional bond fund managers tend to be yield curve-watching maniacs.

I’m going to massively oversimplify some math here, so don’t show this to any bond experts, and especially not to any maniacs, but let’s illustrate why a bond investor might feel so strongly about interest rates by pretending you pay $1,000 for a long-term bond paying you $50 per year.

With me? That’s a 5% yield at the time of purchase.

But suddenly – or next year – prevailing interest rates go way up, and new $1,000 bonds of the same ilk are paying $100 per year, or a 10% yield. Who’s going to want your wimpy 5%-yielding bond?

Nobody! Well, nobody unless you agree to a modification.

You cannot modify the $50 coupon; that’s set. But you can drop your asking price to $500. Now your bond yields 10%, in line with new bonds.

This is both an exaggerated and an oversimplified example. But it’s very true that rising interest rates are the enemy of existing bonds.

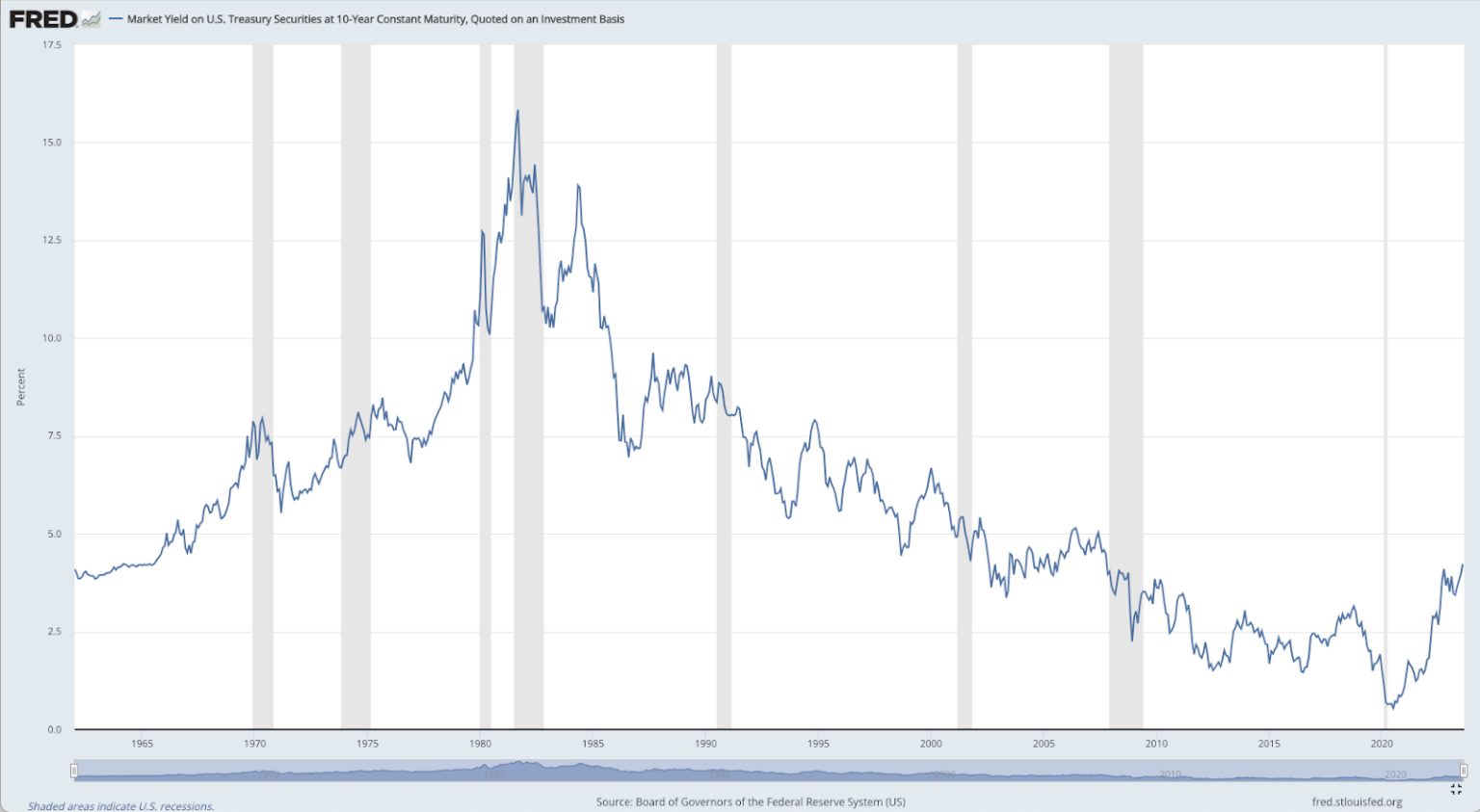

Conversely, falling rates on new bonds make older, higher-yielding bonds look heroic, and if you peek at the chart below showing US interest rates (in this case, 10-year Treasury bond yield, but most other rates would show a similar pattern) from their high point in 1982 ago until now, you can see in one chart why the US has had nearly four decades of a bond bull market – until very recently: Interest rates kept going lower and lower and lower, making all those previously issued higher-yielding bonds more attractive.

Preferred Stocks

Preferred stocks are the ligers – or the Chevy El Caminos, or the Subaru BRATs – of the investing world.

Invented in Maryland in 1836 to sweeten the deal for investors in the B&O Railroad, which really needed money, preferred stock is legally stock but has a lot of bond-like attributes.

Preferreds are either the best of both worlds or the worst of both worlds, depending on whom you ask. The general idea is that preferreds, which tend to be issued by financial companies, give you a higher, safer yield than common shares, but at the price of less capital gain potential.

Preferred stock dividends are paid after bond coupons, but before common stock dividends. Bankruptcy liquidation claims follow the same pattern, although as an income investor, let’s hope you don’t find yourself in too many situations where solvency is an issue.

Like bonds, preferreds are interest-rate sensitive and come with a range of variables like payment, duration (preferreds tend to be either perpetual or 30-year, which is longer than most bonds), and callability (buzzkill alert: most preferreds can be “called” back at the issuer’s discretion after a certain time length or other condition has been met)

Regular preferred stock dividends are taxed at the dividend tax rate, but – and sorry to get confusing – there exist further hybrid categories of securities in between preferred stocks and bonds (picture a liger and a tiger mating to make a interstitial hybrid) whose payouts look and smell enough like bond coupons to be taxed as ordinary income.

Preferred stock usually has a $25 starting “par value” and can be either cumulative (missed dividends must be caught up for by the company when it has more cash) or non-cumulative; convertible preferred stock may be converted into common stock.

I’m not trying to scare anyone away from preferred stock, but would suggest that it’s not the simplest starting point for income investors, even if it can offer opportunities for investors who really want their yield. Just spend some time to make sure you understand the particulars of whatever you’re buying.

Annuities

I don’t like annuities. I don’t like annuities because they violate James Early’s Law of Investing.

The higher the commission paid to someone for selling an investment, the worse that investment tends to be for the buyer.

Early’s Law of Investing

Annuities are often aggressively sold, sometimes through pyramid-ish network marketing cabals that recruit members by boasting about how much money the cabal members are making selling annuities.

Annuities, started by the ancient Roman government to offer retirement plans for its workers, are (these days) contracts with insurance companies. Fixed annuities pay bond-like payments. Variable annuities pass the risk to the customers by paying payments based on whatever funds the money is invested in (like mutual funds) and index annuities combine insurance with a payment tied to the performance of an index like the S&P 500.

I’m not a guru on annuities and annuities have too many variations to cover in a quick segment, but I believe that two points in their favor would be (a) potential tax advantages in certain cases (although Index Universal Life policies are not annuities, they’re similar and often cited in this regard), and (b) a perpetuity “arbitrage” if you’re willing to bet that you’ll live a lot longer than the insurance company paying out a perpetual annuity thinks you will. In fact, now you can buy longevity annuities to specifically hedge longevity “risk.”

Money Market Accounts and CDs

Not long ago, when interest rates were at their bottoms, mentioning money market accounts and CDs in the same breath as “income” would have been a joke. That’s also why they’re not income mainstays; well, CDs let you lock rates in for as much as 10 years (though a few years is more the norm), but money market accounts adjust their yield daily, and are really places to “earn a little something” on money you need to keep very liquid. Neither offers capital appreciation potential, although most investors would consider them effectively risk-free.

All that said, prevailing interest rates are high at the moment, so for as long as that lasts, it’s possible to make a case that money market accounts and CDs are income investments, rather than just cash management tools.

If you’d like more…

As you might guess, I consider dividend stocks the most robust and straightforward way to get income – while also scoring capital gains potential, which is likely attractive to most “income” investors anyway.

Since you’ve taken the time to visit our BBAE site and read my article, I’d like to offer you the opportunity to check out my free report about dividends investing: 5 Secrets to Dividend Investing. In it, I’ll share tips and lessons I learned from 10 years running a dividend research service.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Investing carries inherent risks. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.