Are Markets Becoming Less Efficient?

Cliff Asness is a quant investor who does not act like a quant investor.

He has a PhD in Finance from the University of Chicago, where he studied under Ken French and Nobel Laureate Eugene Fama, academics who ushered in the mostly-now-ushered-out Efficient Market Hypothesis – the once-prevailing wisdom that, at its extreme, said that markets priced in information so efficiently that there’s no point in investing in anything apart from an index fund and government bonds.

Cliff is a billionaire whose AQR Capital Management manages $133 billion using quantitative or semi-quantitative strategies.

But contrary to the mathy, steely-eyed quant investor stereotype, Cliff is known for running hot, whether by sending a scathing nastygram to his alma mater or cursing out people he disagrees with on Twitter.

I’ve made a note not to disagree with Cliff on Twitter, but I admire his authenticity.

In a recent paper he penned for The Journal of Portfolio Management – called “The Less-Efficient Market Hypothesis,” and about whether markets are becoming less efficient – one might wonder if Cliff’s feelings are jostling with his analytical mind. I’m certainly not qualified to out-quant Cliff, but because his paper discusses something that’s relevant to individual investors (in fact, he blames them for worsening efficiency), I thought I’d open up this topic.

Are markets less efficient – or just less rational? And should they be the same?

Cliff – whose firm managed more than $226 billion six years ago, before the COVID bubble and before the Magnificent 7 era – notes that it’s hard to measure or proxy efficiency. Cliff’s right, and in acknowledging that his paper is more of an op-ed than a research paper, he gripes that “rational” investing factors aren’t getting much love, and says he thinks the market has gotten less efficient over his career.

I’m not saying he’s wrong. But I think an efficient market and a rational market can be different things.

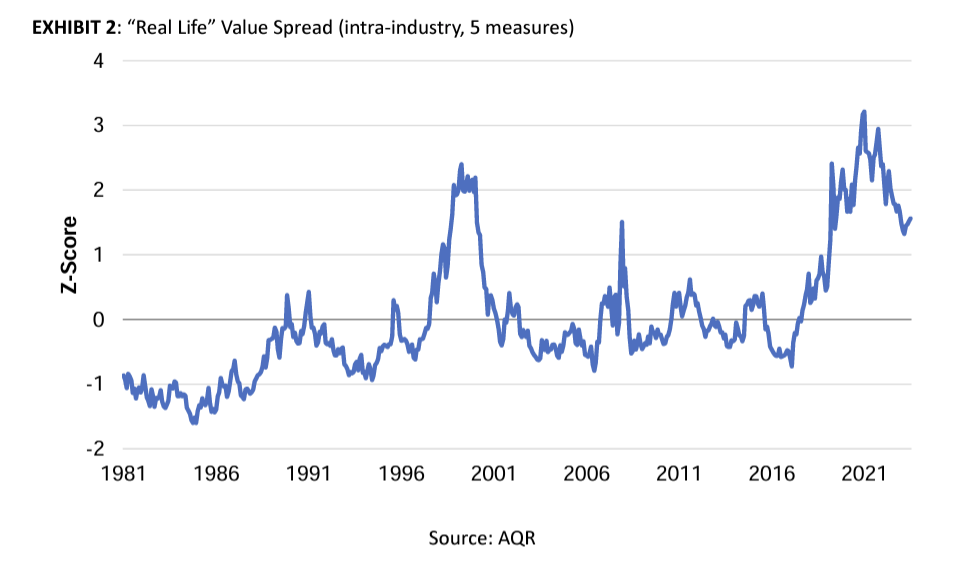

To proxy efficiency, Cliff settles on a five-ingredient “value spread” to show the recently high disparity between the “cheapest” stocks – cheapest by book to price, earnings to price, forward earnings to price, and sales to enterprise value, collectively – and the most expensive ones.

Yes, this spread is absolutely worth noting, and yes, it was recently more extreme than the dot.com era spread, and yes, I’m sure it’s frustrating to have a money management firm whose strategies follow a style that the market hasn’t been appreciating in recent years.

But I tend to think that market efficiency is better defined as the speed and completeness with which the market prices in information, versus what particular information it chooses to price in.

Mine is not necessarily the prevailing view among academics.

Economics is a social science, and humans are herd followers whose preferences bounce around, so the type of information, and the weight the market places on it in setting prices will change with time.

The rub, of course, is mean reversion to economic fundamentals: With what frequency and predictability does it need to happen for markets to be acceptable to non-gamblers?

It may be OK to say the market has been dumber lately, or less rational, because it’s overweighting dumb inputs to price stocks and underweighting smart ones.

But there’s an undiscussed point.

As an investor, I certainly understand the idea of a dumber market. Dumber markets lead to ridiculous highs and ridiculous lows, which are frustrating from one lens but provide investment opportunities if you believe in a forthcoming reversion to “smarter” factors.

But the philosopher in me wants to say there’s a bias in calling the reasons a market is moving stocks “dumber,” because that means there exist some contrasting “smarter” reasons that you think the market should consider when it prices stocks. Should markets be called “less efficient” when they don’t respond to certain factors as much as you want them to?

Again, I’m not against an investor saying the market has something wrong. And it’s OK to blame a market for failing to adequately consider fundamentals, and yes, that could be an inefficiency from a traditional finance perspective.

In fact, like Cliff (but on a much smaller scale), I made much of my investing career doing that, or at least picking individual stocks.

Practically, would anyone say that the AMC “Apes” who pumped a dying move theater stock (which is, now post-bubble, back to being a dying movie theater stock) to its all-time high a few day after a camera fumble revealed that then-CEO Adam Aron was conducting an interview pantless (albeit in his boxers) were smart money?

Yes, it’s “dumb” to buy a stock because you think it’s cool that the CEO does pantless interviews – at least in the sense of that not being an economically sustainable reason for the company and its investors to ongoingly prosper.

But are sustainable factors the only smart ones, even if they’re better for society, and the literature has shown them to be better for investors over time?.

Reason to send the stock to an all-time high? You decide. (Video in many places on YouTube; screenshot from this particular one.)

Was the GameStop craze dumb, smart, or both?

Everyone knew that it was “dumb” discussion-board retail investors who lit the match of GameStop’s rise from a $4 stock to a $400 stock. But they only did the match lighting: After a few days, the institutional money playing on the momentum dwarfed the retail money. Institutions are smart money – so were these institutions dumb for investing in tandem with the retail investors, or smart for trying to prey on them?

And those initial “dumb” retail investors may not have been long term-minded, but they were actually quite ingenious in carefully choosing a stock with low float and high short interest that would thus be disproportionately vulnerable to a short squeeze – a squeeze that worked well enough to start a mini-movement, drive hedge fund Melvin Capital out of business, and prompt a Congressional inquiry into a brokerage.

Long term-minded? No. Sustainable? No. Using factors based on traditional economic fundamentals? No.

But their way of making money worked, at least for a while – both with the help of some smart money and at the expense of other smart money.

Back to Cliff:

“If you asked me in, say, 2002, after we survived the dot-com bubble (and prospered round-trip), whether in my career I’d ever see disparities in pricing that large again, well I hope I’d be smart enough not to offer guarantees (a stupid thing to do in our volatile business), but I’d probably have said “I really don’t think so.” After all, 1999-2000 was the most extreme thing we had seen in 50 years, and 20 years later seems like a short time for even imperfect markets to forget (for instance, people like me who lived through it and prospered from it would still be around!). And yet it happened. It took COVID to push the spread past 1999-2000 (and all those COVID-era predictions that super expensive stocks would all be worth it, and cheap stocks would go out of business – ex ante silly to many of us – ex post did turn out to be wrong). But even before COVID, spreads were getting close to the 1999-2000 peak, something that indeed shocked out of me whatever vestige of pure EMH worship I still had!”

Are markets becoming less efficient, or have recent markets just prioritized factors that Cliff doesn’t like?

I’m not taking a swipe at Cliff. His piece is good food for thought, and I’m digesting his thoughtful ideas.

And a counterpoint to my counterpoint is simply that bubbles aren’t supposed to exist in an efficient market (as bubbles would suggest mispricing, which efficient markets can’t be guilty of). I am a strong believer in bubbles.

Cliff offers three ideas as to why markets have become less “efficient:”

- Indexing may have ruined the market: Indexing, of course, is nondiscriminatory money that invests only for a binary reason: whether or not a stock is in an index. Cliff doesn’t lean too hard into this but says that if more smart money than dumb money has moved into indexing, it could be a reason the market has become “dumber” (less efficient, in his parlance) lately. (Bloomberg’s Matt Levine takes the other side, saying that with more money in index funds, active management would seem to offer more opportunities for smart money.)

- Super low interest rates for a super long time have made investors go “cray-cray” (Cliff’s term): I do like Cliff’s style. If we suspend the inefficient-vs.-irrational discussion and ask: Did low interest rates contribute to investors deemphasizing wholesome, long-term fundamental factors that have been shown over time to connect with stock price returns?, the answer is definitely “yes.”

- Social media is turning investors into herd-following morons (my word): Per Cliff: “IMHO, this is the best of my three hypotheses.” I tend to think this is very, very true for certain stocks, or even certain categories of investments, but it’s far from true for the whole market.

I agree: Markets are becoming dumber

I actually agree with Cliff’s sentiment, even if I quibble with his nomenclature (which is mostly the nomenclature of traditional finance, to be fair). The market has departed from sensible economics – the kind proven by mean reversion over many decades, the kind that does good for society by routing capital to well-performing companies and away from badly performing ones, the kind that’s shown by academic research to be best for investor returns over the long haul, and the kind that’s presumably best for AQR.

Cliff notes a 2023 line from Warren Buffett:

“For whatever reasons, markets now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young.

So what should you do?

Again, I agree with Cliff, who hopefully now feels less need to curse me on Twitter: “So, pushing yourself (and whoever you report to!) to have the longest time horizon possible is definitely #1 on the list.”

Yes. Mispricings are prone to correcting themselves. A more irrational market will create more mispricings, but might also take longer to correct them.

I’m honestly not sure whether:

- Technology, increased ease of trading, and involvement of more Average Joes in the stock market is “better” at bringing out some inner animalism – our urge to gamble, to move as a herd, to buy stocks of companies led by pantless leaders (in fact, specifically because they’re led by pantless leaders).

- The exponential advancement of technological progress (and, therefore, societal value addition) is creating more potential big winners than ever before, thereby justifying some of the “bubble,” or

- Whether prolonged low rates simply created a market fad favoring speculative investments that will run its course, and preferences will shift back to tried-and-true factors sooner or later.

Or maybe a mix of all of these?

The one core truth is that for an investment to sustain its value, the underlying business must add sustainable value.

In support of Cliff, I believe that AQR will do that over time.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.