BBAE’s InsiderEdge Gets Benzinga Award Nomination

We at BBAE were delighted to receive both an invitation to Benzinga’s 2024 Fintech Deal Day and Awards conference and a nomination for Best Investment Research Tech for BBAE’s InsiderEdge.

I’ll explain BBAE’s InsiderEdge tool and the logic behind it in a moment – it’s based on research that’s both credible and compelling.

First, though, a bit about Benzinga’s event itself, which was held at a venue called Convene in the swanky Brookfield Plaza in lower Manhattan.

Benzinga 2024 Fintech Deal Day and Awards

Benzinga’s event was a heavy-on-networking affair with spades of trading industry attendees as well as vendors offering stock charting software, digital annuities, ETFs and ETNs, trade clearing, and plenty more. The vendors were mostly founders or very senior management, so the folks there knew their stuff.

Benzinga had a full day of speakers and panelists, too – even before the awards – with sessions running the gamut from payment technologies to the importance of content in the investment industry (a personal favorite for obvious reasons), to crypto.

I don’t have space to walk through every session, but a surprisingly interesting one was about moving from T + 1 settlement – settling a trade the day after the trade day, which itself is a new thing, following T + 3 and T + 2 – to continuous settlement, which the panel feels is coming down the pike. Without getting into the sleepy details, settling trades instantly seems easy from a distance, especially in our high-tech age, but in fact requires a ton of scrambling behind the scenes, especially with trades from institutional investors who often need a few days to call in the cash or stock they intend to trade.

BBAE InsiderEdge and Benzinga award nomination

BBAE had the privilege of being one of four finalists for Benzinga’s Best Investment Research Tech category for our InsiderEdge feature. (You can see an example of InsiderEdge analysis here.)

Before I explain InsiderEdge, let me first explain why corporate insider trading is considered both a powerful signal for investors and a murky area legally and ethically for corporate insiders (but not for investors who follow their trades).

Insider trading: Actually not a simple issue

Strictly speaking, the US has no law against insider trading.

Insider trading – let’s initially picture a clearly “bad” version, such as an outside counsel trading in advance of a merger that she is working on – does get prosecuted, if sparingly; much modern enforcement hails from a 1997 Supreme Court case law interpretation of the broader “manipulative and deceptive practices” banned by the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. Because there’s no statute banning insider trading specifically, “misappropriation of information” is commonly cited as the violation in insider trading cases. In this case, the lawyer would have misappropriated the confidential information shared with her.

The first academic look into US insider trading was from legal scholar Henry Manne, who penned Insider Trading and the Stock Market in 1966 and – surprisingly – suggested insider trading to be a good thing because it increases market efficiency. Those holding that view point to how Japan’s outlawing of insider trading in 1988 contributed to a market crash and a 77% plunge in trading volume (I’d add that outrageous valuations contributed, too).

But let’s talk about trades by corporate insiders – upper management, basically. By nature, these folks have better information – much of it confidential – about their company than anyone else. Is it fair that they should trade on that?

You might reflexively answer “no.” But the only way to truly not let insiders trade based on material nonpublic information would be to ban them from trading until they no longer possess material nonpublic information – a gradually-arrived-at situation which occurs not only after they’ve left the company, but presumably after some additional time (say, 6-12 months, though in a pure sense, time would vary based on how long the information retains the potential to move stock prices) to be good and sure that their prior insider information has gone “stale.”

Problem is, such delayed liquidity would likely scare top talent away from publicly traded firms, or at least away from having long, value-adding tenures there.

Corporate insider trading has clear and unclear elements. For example:

- Clear: If a CEO (or CFO/COO/etc.) wants to buy some stock because he or she has faith in the long-term future of the company, that’s OK. In fact, that’s good. Such a trade isn’t exploiting nonpublic information.

- Clear: If a CEO knows his or her company will issue an acquisition announcement in a few days, and that announcement will drive the stock price up, buying stock right before the announcement (and, especially, selling it shortly after the announcement) is not OK. Such a trade exploits nonpublic information.

- Unclear: But what if the CEO thinks there’s a possibility the company will be bought in the next year, but there’s no offer and no definitive talks yet? Gray area, amigos.

- Unclear: Or what if the CEO wants to sell shares over the next three months to buy a house – and a definitively adverse news announcement will happen then? Obviously a no-no. But what if that adverse news is just potential? Then it’s gray.

There are many gray areas for corporate insiders. One attempt at remedy was Rule 10b5-1, which allowed insiders to trade via “prearranged plans.”

Prearranged plans sound wholesome, and many in the investment community assumed 10b5-1 trades were innocuous. But Alan Jagolinzer, Vice Dean of Cambridge Business School and formerly of Stanford (and a good friend of mine, in fair disclosure) did research into 10b5-1 plans in the early 2000s and found that they were being abused by corporate insiders.

As you can see from Alan’s graphs below, corporate insiders have the Midas Touch, even when supposedly trading “blind” via prearranged plans: As if guided by clairvoyance, insiders set their prearranged plans to sell at very peak prices (first graph) and buy at nadirs (second graph).

In fairness, the US has seen further regulation since Alan’s study, and – in fact, it’s because of Alan’s study, as well as the work of Dan Taylor at Wharton. So 105b-1 plans have gotten harder to abuse, and I would be curious to see what Alan’s graphs look like with current data.

Corporate insiders clean up. Is that OK?

But using the data we have, it’s fair to say that as a group, the best investors aren’t hedge fund managers, mutual fund managers, pension fund managers, Congressmen and Congresswomen (though they come close) or individual investors. They’re corporate insiders, and by a longshot. One study called Estimating the Returns to Insider Trading: A Performance-Evaluation Perspective (Jeng, Metrik, and Zeckhauser, 2003) found that a portfolio of insider buys outperformed the market by 11.2 percentage points annually!

To be clear, that’s not returns of 11.2% per year. It’s earning 11.2 percentage points of return on top of what the market does.

People don’t beat the market by 11.2 percentage points annually by being lucky. Incidentally, the key point that Jeng, Metrik, and Zeckhauser found was following insider buys; insider sells contained little useful information.

To answer the subheader’s question, it’s probably not OK for corporate insiders to score unsportsmanlike profits from trades informed by nonpublic information. Interestingly, the reasons are arguably more for principle than economic: That same Jeng, Metrik, and Zeckhauser study found that insider trading costs regular shareholders just 10 cents of return for every $10,000 invested.

But for now, reality is what it is, and there’s an if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-em argument from an investor perspective for using, or at least considering, the signals produced by insider trades.

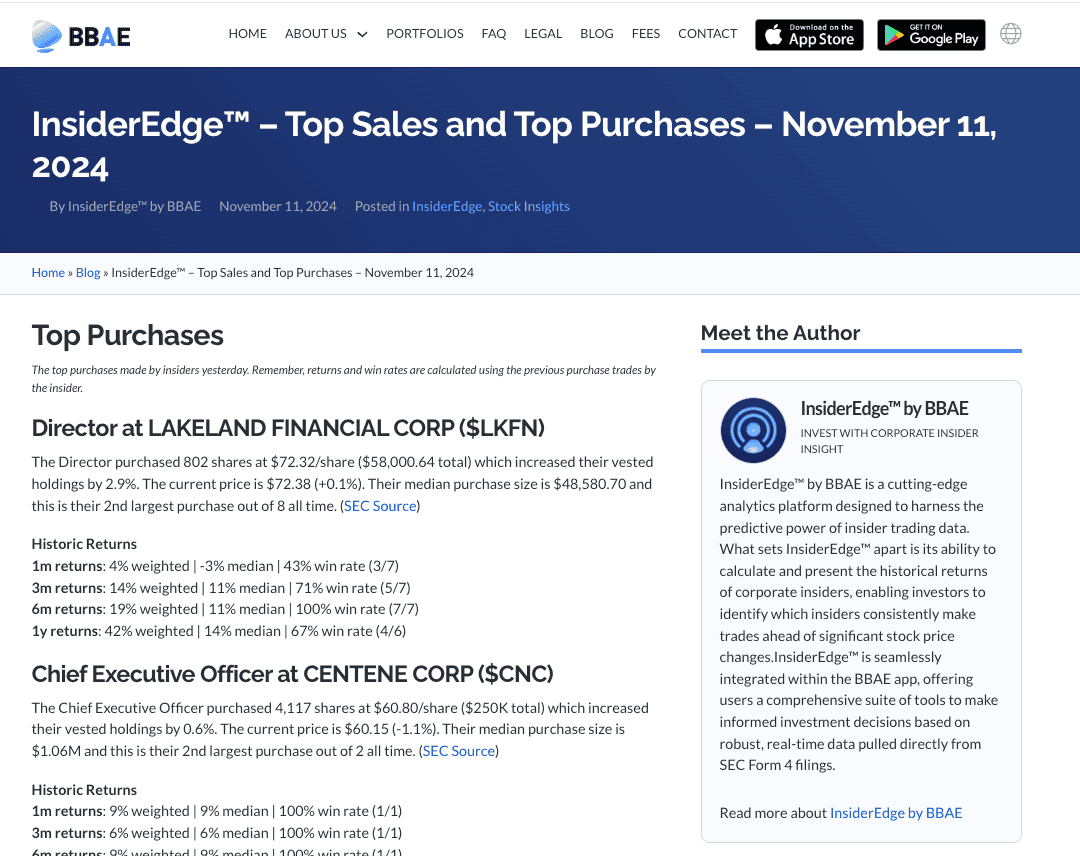

InsiderEdge aims to do that for BBAE account holders. It looks at corporate insiders’ trades while also displaying the short-term performance of those corporate insiders’ prior trades. The idea, of course, is that insiders whose trades have tended to perform well may provide a richer signal than those who truly buy and sell at random times (though ironically, a case could be made that their companies are likely more honestly run).

Here’s a screenshot of InsiderEdge below:

Returning to the Benzinga event, while InsiderEdge didn’t get the award this year, there’s always next year – and plenty more in the pipeline for our account holders at BBAE. We’re grateful to have been a finalist.

If you’re new to BBAE, please subscribe to the BBAE Blog, and if you’d like to see how we can power your investing (and get some cash back) click right here to open an account.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.