The story and causes of Silicon Valley Bank’s demise are well-publicized by now; they were less so when I penned this BBAE Forbes column on the topic (reminder: please subscribe to this blog if you like it, and you can even “follow” the Forbes column, too – look for the blue button on the right, just under the headline).

(Speaking of which, click here to get a special offer for opening a BBAE account.)

Besides a run-down on the SVB drama itself, I make what’s perhaps a more enduring point about the effects of rising interest rates on cash flows.

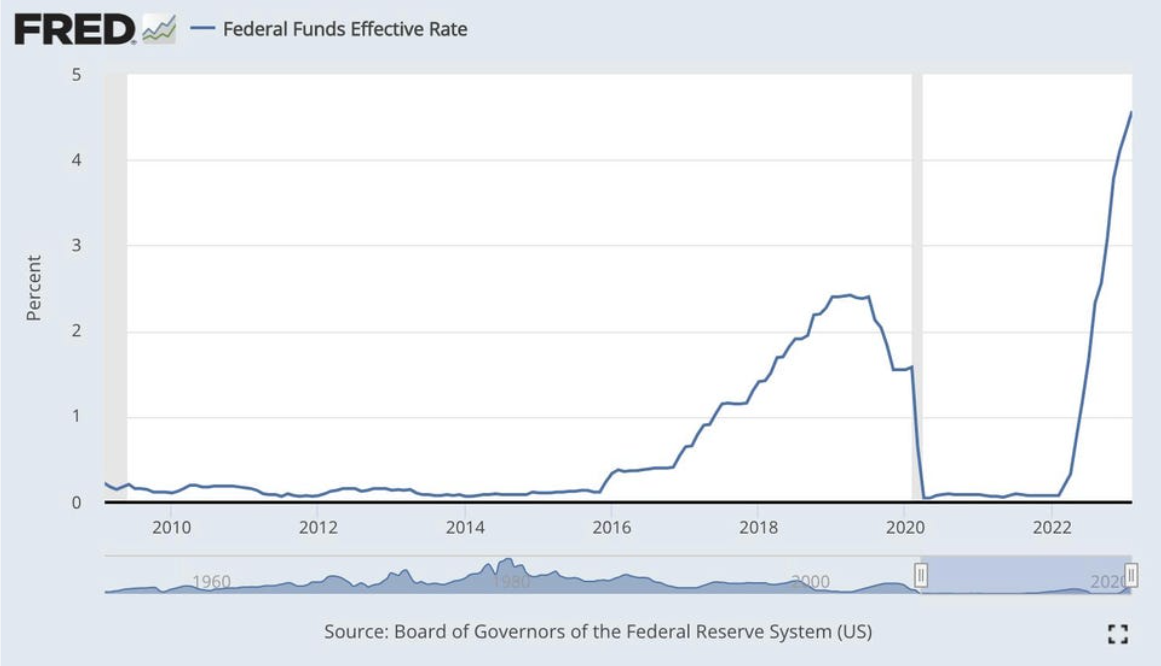

Everybody reading this is likely aware of the recent rise in US interest rates, which demonstrated that long-dated Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (which SVB bought with depositor funds) may not have had much credit risk, but had plenty of interest-rate risk.

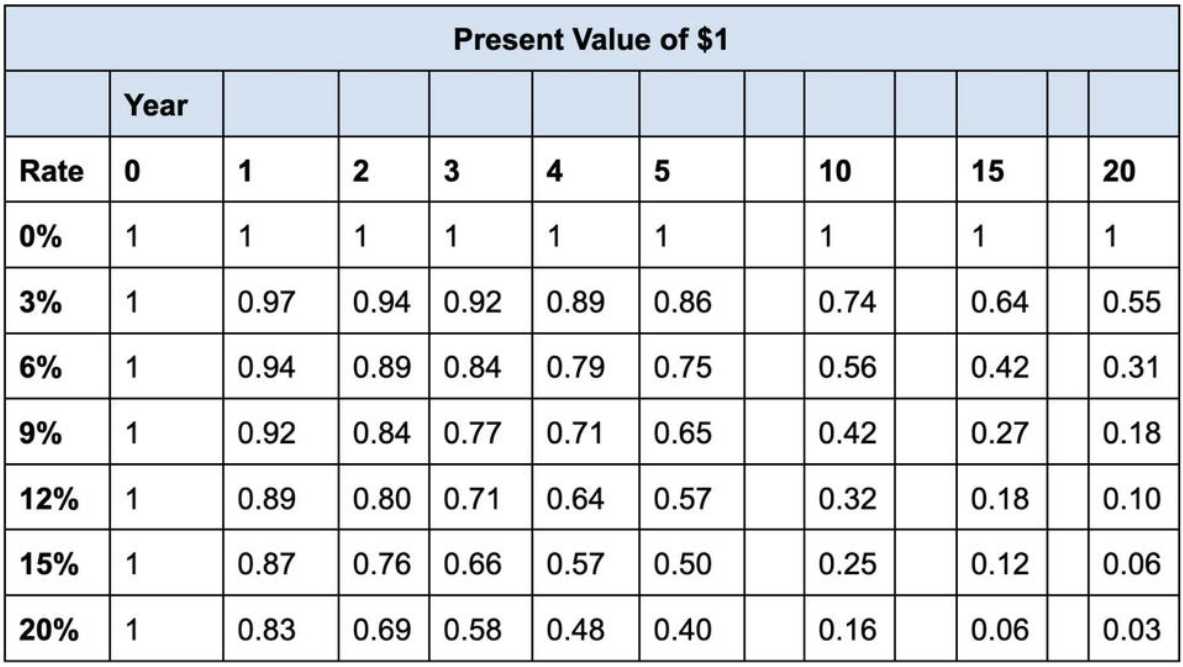

The key point is that the further into the future a prospective cash flow is, the lower its present value. This effect is always true, but the higher the interest rates, the more it’s magnified.

For this same reason, biotechs and startups who bleed money initially in hopes of windfalls five or 10 years into the future see their values maximized in a low-interest rate environment. It’s why we had such a growth stock bubble or quasi-bubble for the past 12+ years.

SVB made a move – going long to squeeze out a bit more interest income – that would have been OK in the low-rate environment, but which was absolutely not OK in the most rapid rate hike in US history.

Have a look at this table, which I shared in my Forbes piece. It explains both the SVB blowup and the growth stock era in one graph.

James