Is India the Hottest Market to Buy?

India’s stock market has almost tripled from its COVID lows.

With a PE of 24, it’s currently one of the most expensive of the world’s major stock markets (incidentally, the S&P 500’s PE is also 24).

It’s also highly volatile, dropping 6% after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party failed to win a majority vote (Modi is still the PM, his party doesn’t control Parliament).

Are Indian stocks worth buying?

We’ll take a quick look.

First, let me tell you why India popped up on my investment radar in the first place. MarketGrader is a smart beta research firm with a history going back to 1999, and MarketGrader’s ratings have done pretty well – over the past 10 years, 90% of MarketGrader indices have beaten their benchmarks.

MarketGrader uses a 24-factor model that incorporates a range of factors, straddling, value, growth, and momentum, with the intent of giving signals that are robust to various market conditions.

Given its results, when MarketGrader’s model talks, I listen.

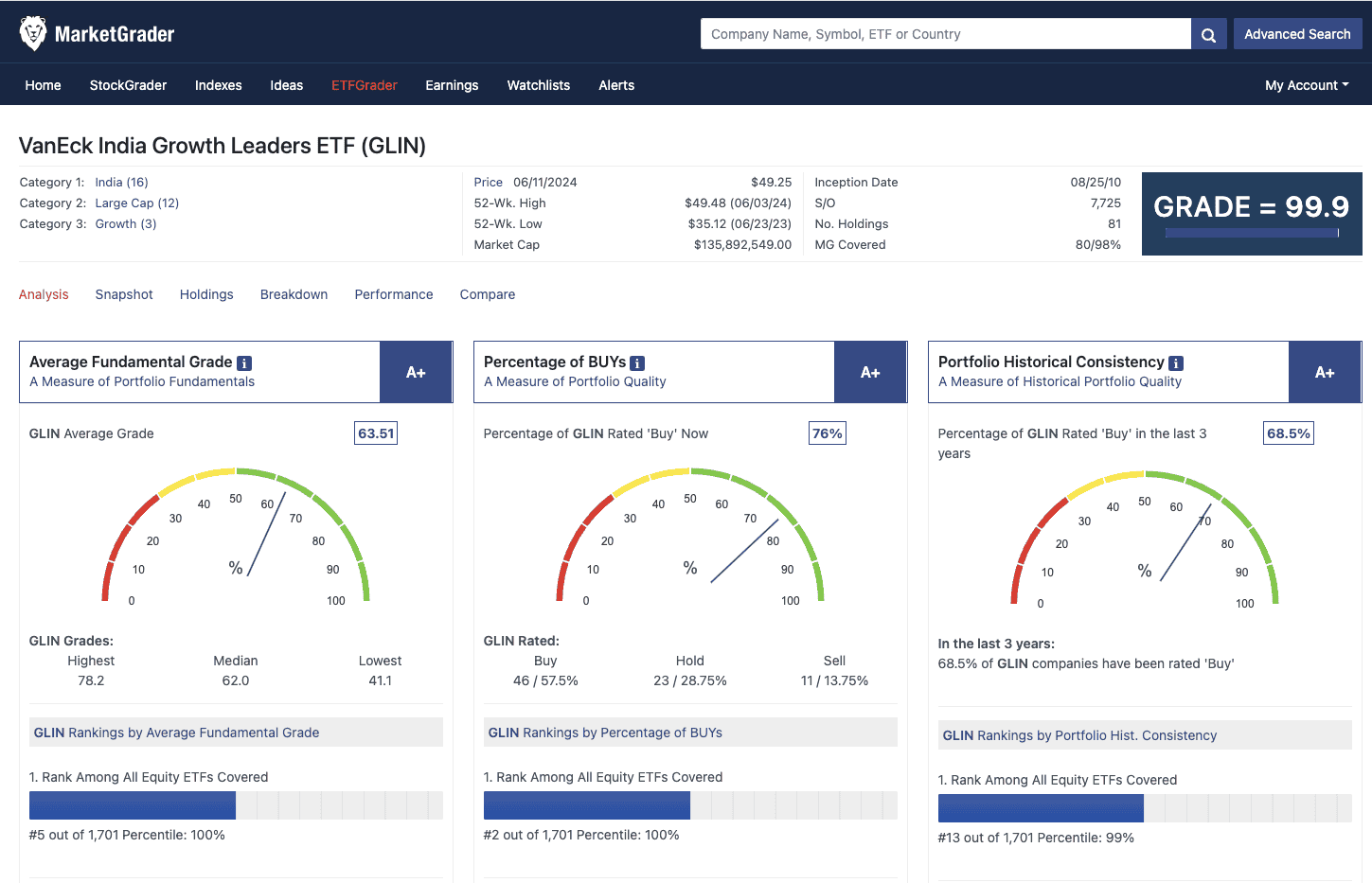

And when I went to MarketGrader’s ETF Grader page (the model grades stocks as well as ETFs), I saw that the very highest scoring ETF was the VanEck India Growth Leaders ETF (NYSE: $GLIN), which is up 13.45% year-to-date.

India?

We’ll get to that in a moment. A few points about the ETF first:

MarketGrader’s rating may be axiomatic to a degree: This ETF is based on the MarketGrader India All-Cap Growth Leaders index, so it’s not surprising that the MarketGrader model likes an ETF that follows one of its own indexes.

That said, ETF Grader rates all kinds of ETFs and the top ranks are not dominated by MarketGrader-inspired ETFs, so it caught my eye that the model loved this particular ETF so much.

The VanEck ETF carries a 0.87% net expense ratio (on the high side compared to a US-focused ETF but in keeping with emerging market ETFs; just note that this ETF’s gross expense ratio is higher, at 1.09; VanEck has agrees to waive some fees until at least May 2025, but the fees could go up then), was founded in 2010, and has about $145 million in assets – not huge, but sustainably large.

Why might Indian stocks be attractive?

Considering that it’s much easier to invest in a US-traded ETF that owns Indian stocks than to actually invest in Indian stocks, I’ll speak about India in general, because that’s the perspective relevant to an ETF investor, and in particular to investors interested in the VanEck India Growth Leaders ETF, as it seeks to “represent the entire Indian opportunity set regardless of size.” Fitting to MarketGrader’s philosophy overall, its investing prism is GARP, or growth at a reasonable price, and it’s not weighted by market capitalization.

Given how well India’s stock market has performed, the real question may not even be: “Why might Indian stocks do well?” Some of the reasons are fairly obvious: India has a young, tech-savvy, English-speaking populace – the largest in the world now – good food (granted, that’s not market-related, but I’m certainly a fan), and is benefitting from not only its own modernization but also from global firms increasingly seeking to move operations or sourcing out of China.

India surpassed the UK to become the fifth-largest economy in the world last year, and is set to overtake both Japan and Germany to claim the #3 position by 2027, per Morgan Stanley and as cited in this BBC article.

The better question is: Is there much upside left in India at current prices? Or, phrased differently: Why does MarketGrader’s model love Indian stocks so much when they seem so richly valued?

Let’s look more at India.

COVID aside, India’s GDP has grown roughly between 6% and 9% annual over the past several years, and is expected by the IMF to grow by 6% to 7% over the next five years, outpacing both a slowing China and the global average (typically around 3.5% per year).

The IT industry in India has grown at a 10% compounded annual growth rate (CAGR), and the pharmaceutical industry is expected to grow at a 12% CAGR over the next five years.

Why did Indian stocks rise and then fall around Modi’s recent election?

Shortly before India’s recent election, its stock market rose 3% in anticipation of another landslide win for Modi. Following Modi’s non-landslide win, the market fell 6%.

Modi takes heat for being dictator-ish, for jailing journalists who say things he doesn’t like, for being so anti-Muslim that he was banned from the US for 10 years (technically he failed to stop anti-Muslim riots), and for being so insecure that he can’t handle any debate or questions, according to political scientists like Christophe Jaffrelot, as quoted by CNN. He’s also criticized for underfunding both education and healthcare (registration may or may not be required, depending on how many Bloomberg articles you’ve read recently), and for fostering a system that enriches those of mainstream ethnicity (especially the wealthy class) at the expense of marginalized minorities.

“He liked acting in school plays. He always wanted to have the lead role. If the lead role was not given to him, he would not act in the play at all.”

-Modi biographer Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, as quoted by Rhea Mogul of CNN

Modi, who is single after running away from his arranged marriage at 17, apparently employs a big PR team to keep his personal life out of public discussion.

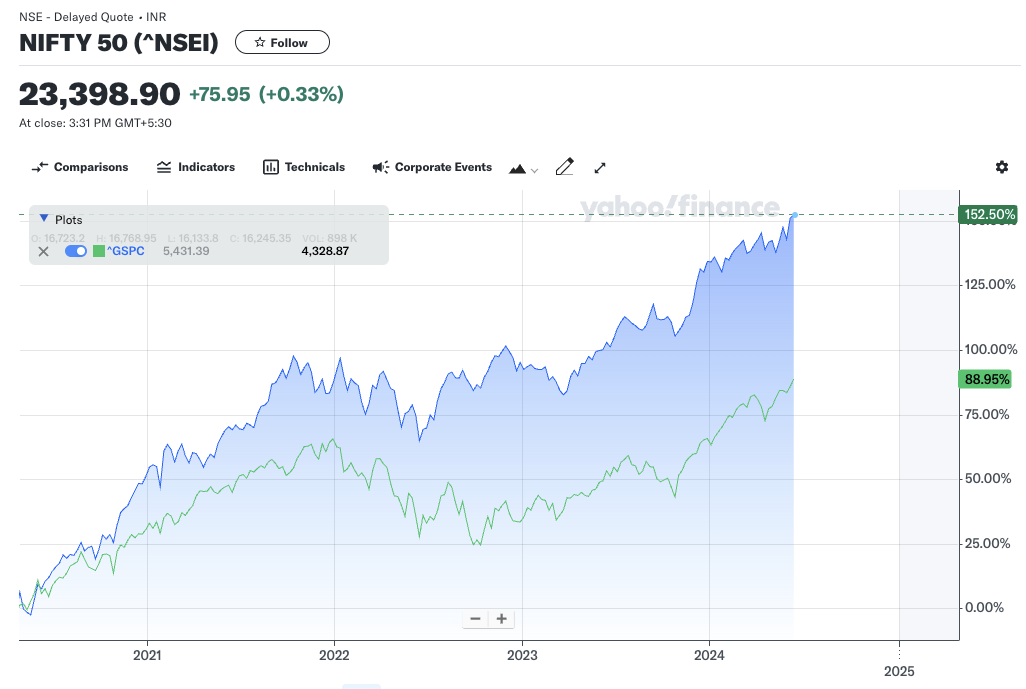

But Modi has also been very good for the stock market – which, thanks in part to big Indian infrastructure stimulus, has easily outpaced the S&P 500 (green line on the chart below) since COVID-era lows. (The NIfty 50, a re-use of the name of a US large-cap index popular in the 1960s and 1970s, is India’s most-cited stock index.)

And Modi is just plain popular, even if no longer landslide-level popular. Over the years, his approval had ranged from just below 70% to more than 90%, depending on the poll (see the green column below).

How India’s election works

What spooked the market was news that despite Modi’s supposed monster approval rating, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) didn’t do as well as expected.

The prime minister is not directly elected in India. Rather, citizens vote for representatives in the Lok Sabha, or Lower Parliament, which has 543 seats. If one party gets at least 272 seats (just more than half), its representatives can go beyond just electing their party’s PM candidate; they can form a majority government. In 2019, Modi’s BJP got 303 votes, making this easy. This year, they got just 240 – enough to elect Modi as PM, but not enough to give his party a Parliamentary majority.

What’s the issue? Modi’s still popular, but markets seem to be worried that Modi, perhaps in a manner reminiscent of his reported childhood theater behavior, can only function well when he holds near total power. They’re worried that he can’t play nice with others, and in a situation where he’s questioned and can’t always get his way, India’s governance could deteriorate.

“‘Negotiating and forming a coalition, working with coalition partners, grappling with the tradeoffs that come with coalition politics — none of this fits in well with Modi’s brand of assertive and go-it-alone politics,’ said Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute.”

-Excerpt from an Associated Press article by Krutika Pathi

Will it? That’s above my pay grade. But it seems to be what’s spooking the market.

The wisdom (or non-wisdom) of quant investing

From one lens, it’s easy to look at a situation like this and say: “Aha! This is the kind of situation where a quantitative methodology like MarketGrader’s fails you. The model is sensing a security that’s been on a tear – a good sign, at least for momentum investors – and had a recent setback; it probably thinks it’s time to buy the dip, but a human can see that this situation is rife with one-man political risk, which is extremely non-quantifiable and thus hard to predict.”

That’s one view, and it’s at least partially true.

The other view is that when a security is on a tear and suffers a setback, there’s always a reason. And we, as humans, suffer from all sorts of cognitive biases in investing, many of which cause us to overreact to negative news (and overreact to positive news, too, for that matter; we’re jumpy). In the long run, things have tended to work out better and more smoothly than our human brains think.

This view is partially true as well, at least I believe so.

Do you bet on the quantitative factors, or the qualitative ones? The whole point of profitable investing is that there are no definitive answers to such questions. And I certainly can’t tell you.

But I can tell you that from an idea-generation lens, MarketGrader is doing its job. I wouldn’t have considered (or even thought of) investing in India had I not seen its rating. Now I’m weighing it.

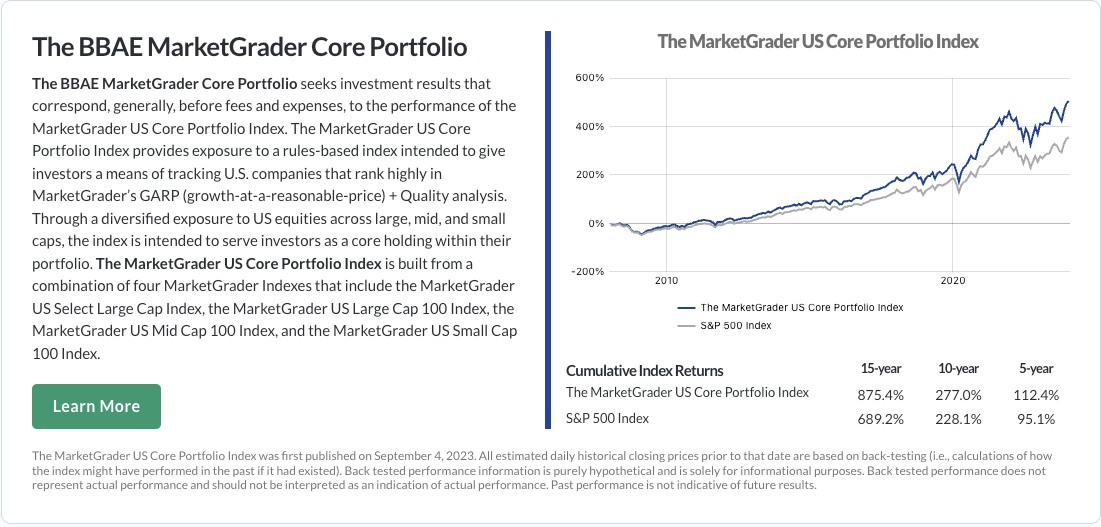

MarketGrader does more than generate ideas. At BBAE, we use it to power three separate managed account products (with minimums of only $2,000, versus the $50,000 and up you might find elsewhere) that are all based on models with strong test results (importantly, test results don’t necessarily equate to future results, but you’ve got to start with something and so far, the real-life BBAE MarketGrader portfolios are beating their benchmarks, just as intended).

I’ve shown a screenshot from a sample portfolio below; more information about it and about our two others – one is aimed at growth investors and one combines income and growth – right here.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.