Is This Time Different?

Pretend you alone know that a huge diamond – perhaps the size of the $350 million Hope Diamond – is buried under a small public company’s headquarters.

Pretend the building itself cost $5 million to build, so even if the entire headquarters has to be demolished to get to the diamond, that plus any business disruption costs would almost certainly be worth every penny.

Would you buy the stock?

From one lens, equity investing has two fundamental notions:

- The value a stock is supposed to have

- Whether or not a stock actually moves to that value

Rewritten: in investing, it’s not enough to be “right.” Because economics is a social science, you need to be right, and then you need some mass of people to come along and actionably agree that you’re right.

You might be able to persuade the company to destroy its headquarters in pursuit of a monster diamond that you claim is there, but it’s going to take some work.

When you buy a stock, you’re basically declaring (with your actions) that the stock price should be higher. This means the question of stock price obedience to or migration to “correct” values applies to nearly all investors.

But because individual predictions are hard and not especially newsworthy to study, analysts and academics tend to focus on something easier: mean reversion.

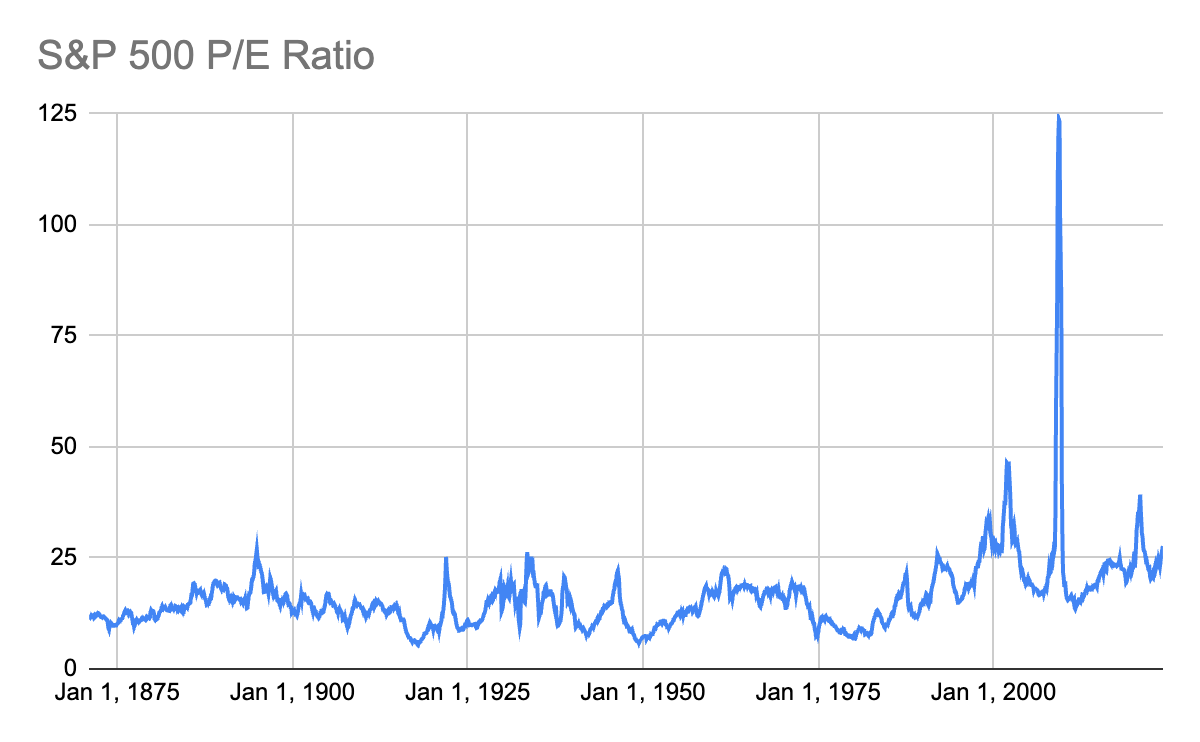

Data source: Multipl.com

For instance, the S&P 500’s current P/E is 27. But its mean is 16 and its median is 15.

So is it overpriced? Is it supposed to return to the mean/median? Will it?

These are existential, or at least contentious questions, it turns out.

Does the P/E ratio mean revert?

Sam Ro, penner of the excellent Tker.co blog, examines this issue in his recent blog post (subscription may be required), largely by referencing a research note from Bank of America analyst Savita Subramanian, who basically argues that today’s S&P 500 has:

- Half the leverage

- Lower earnings volatility

- Higher earnings quality

- A greater proportion of asset-light businesses

than in prior decades.

In other words, this time is different: today’s market is “better” and thus deserves a permanently higher valuation.

Without stealing Sam’s thunder, I’ll say that he shows some charts to confirm the lower debt and asset-light bits, and adds one about increasing worker productivity.

I’ve seen the “higher P/Es are justified because this time is different” argument made to include a few more points, too:

- Trading costs are cheaper these days

- Diversification is cheaper

- At least from 2009 until 2022, the US had low interest rates

Blogger Nick Maggiulii makes some of these points here. They feel reasonable.

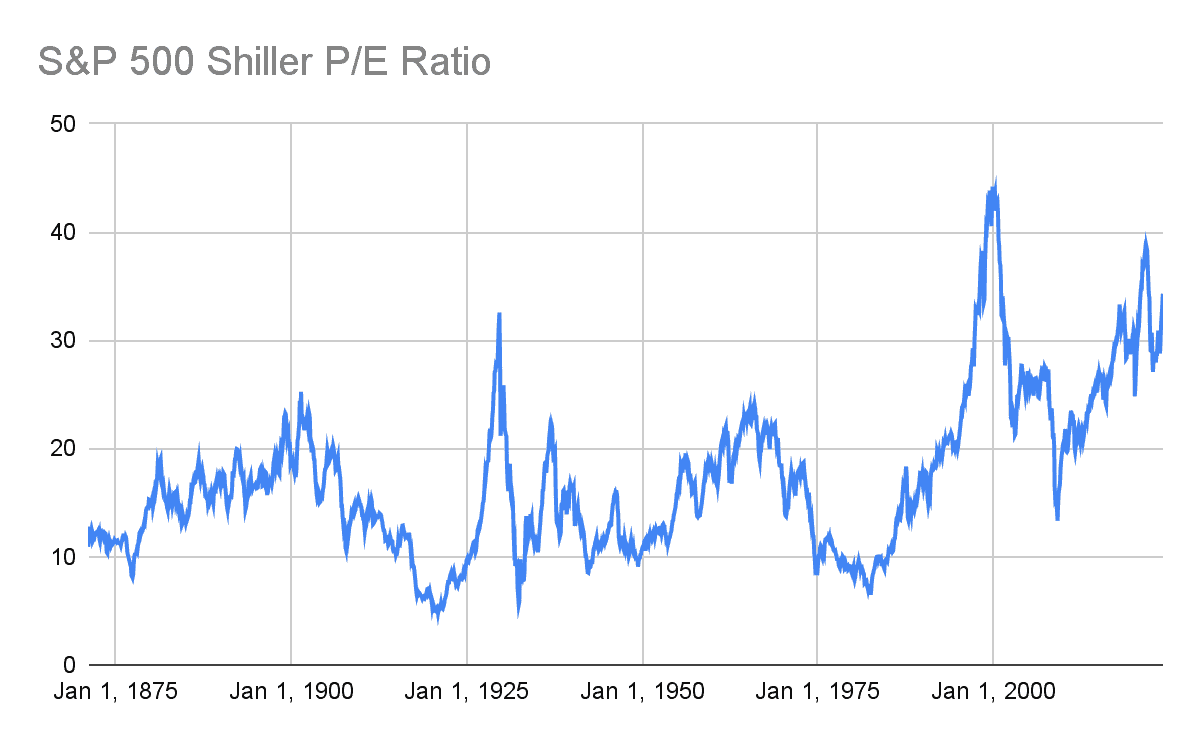

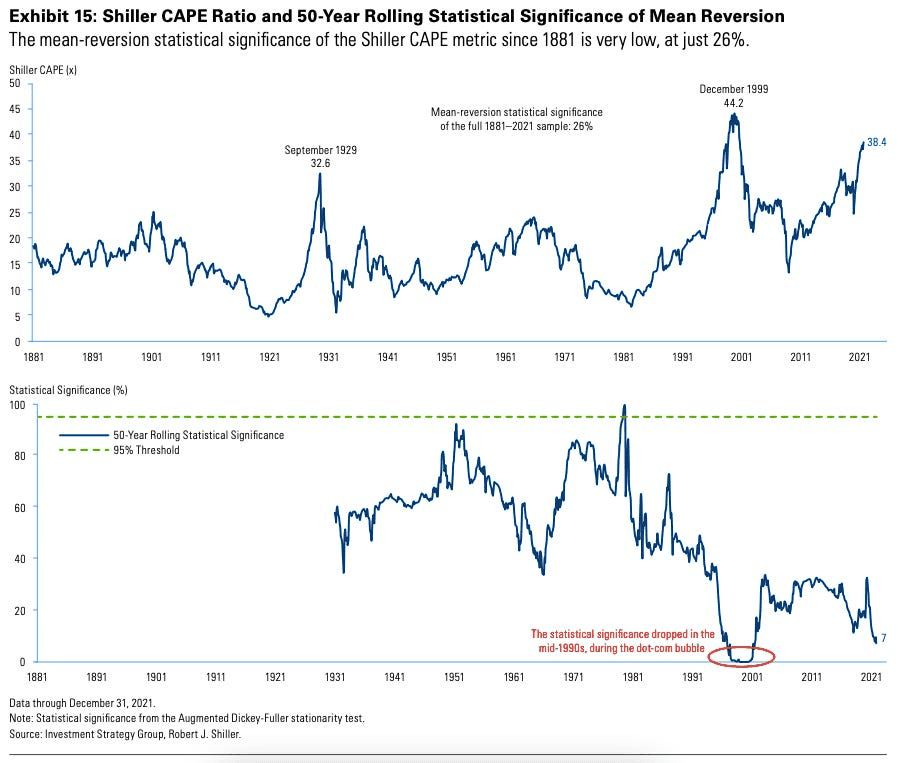

And Sam has covered mean reversion (or lack thereof) with Robert Shiller’s trailing-10-year P/E ratio before. (The Shiller P/E, instead of using just the recent 12 months of earnings as the denominator, uses inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 10 years.)

Data source: Multipl.com

Goldman Sachs analysts, Sam notes, found no statistical evidence of mean reversion in the Shiller P/E. I am not a statistician so I can’t attest to the validity of Goldman’s analysis, but Goldman’s other point is that because the Shiller PE uses trailing 10-year earnings data, you could be waiting a long time for mean reversion:

To quote Sam’s own quoting of Goldman:

“For example, the Shiller CAPE entered its 10th decile in August 1989 but did not revert to its long-term mean for 13 years.”

Source: Goldman Sachs, via Sam Ro/Tker.co

But as you can see from the second chart, the statistical significance itself varies quite a bit.

A statistic for any viewpoint?

Is it possible that this issue belongs in the same bucket as the “benefits” of emerging markets, the Piotroski score, equal-weight S&P outperformance, and probably quite a few other things that are “kinda true” sometimes and “kinda not true” other times?

Investing being highly ambiguous, and the human mind being what it is, it’s not impossible to see – and I’m not necessarily saying this is happening here – someone make a name for him- or herself by culling some numerical “truth” from the ether, and then a debunker comes along with an alternative “truth” – when, in fact, they’re both looking at partial truths, meaning that neither is fully right nor fully wrong.

Beware the confident social scientist, in other words.

Why I trust very few “numbers” in investing anymore

A young Kevin Klassen, formerly a student at Gettysburg College, would beg to differ with the above debunking, writing in the Gettysburg Economic Review that P/E ratios do mean-revert, or at least they did between 2008 and 2017, and in fact that P/E reversion happens more quickly than price (“P”) reversion.

Kevin was a student, so in a Kevin-vs.-Wall Street battle, Wall Street would win on credibility. But then there’s Jason Hsu, founder of Rayliant and co-founder of Research Affiliates (Rob Arnott is the other co-founder), the best-known and best-regarded smart beta firm. Jason is concurrently a professor of finance at UCLA and has authored more than 40 peer-reviewed articles.

Jason would win in a credibility battle against a Wall Street analyst, and he, like Kevin, says there is mean reversion (at least sometimes).

And then we have these guys (Wiegand and Irons, 2005) who say that there’s no mean reversion, and thus high P/Es can stay high.

And then we have these other guys (Becker, Lee, Gup, 2010) who say that yes, P/E ratios are mean-reverting.

Welcome to the social sciences, guys.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.