Magnificent 7 Boosting Cash Flow from Stock-Based Comp?

Making the rounds in financial circles is a report about free cash flow and stock-based compensation by Miller/Howard Investments, an investment manager based in the Catskills with $3 billion under management.

One takeaway is that Magnificent 7 stocks like Nvidia are, on a free cash flow basis, more expensive than they seem. And dividend stocks are cheaper than they seem.

But, really – and I mean this with all due respect, I see this as mixed-bag research that’s somewhat biased, but with a conclusion I very much agree with. Let me explain.

What is stock-based compensation, and why the fuss?

In the old days, corporate managers were paid in cash. With the 1990s tech boom, cash compensation became supplemented with or partially replaced by company stock, and/or options to buy stock. The internet was exploding, companies were rushing to catch the wave, and while they were becoming rich in stock price, early-stage tech companies were mostly losing money, so to attract top talent, they “paid” in equity.

This itself was not nefarious – in fact, ownership aligns managers with shareholders.

But these equity “payments” didn’t appear on the income statement because accounting standards hadn’t caught up to current business practice. And companies fought tooth and nail to keep non-cash executive compensation off the income statement because they wanted to report bigger profits.

At the end of 2004, the FASB decreed stock-based compensation must be expensed. The ISAB acted a little sooner. (A big debate had been valuation, especially with unvested options, whose values at grant time were fuzzy, but nonzero.)

But – and if you understand accounting, you know that the statement of cash flows undoes accruals (non-cash inflows or outflows) that were “done up” in the income statement and balance sheet changes – because stock-based comp is a non-cash expense, it gets added back to the operating paragraph of the statement of cash flows in reconciling cash flow from operations.

| Accrual accounting mini-primer: If the above paragraph makes no sense to you, know that to better represent economic reality than cash-based accounting (which, as it sounds, simply records cash going in and out), accounting standards setters created accrual accounting, a method that attempts to better represent the economics of certain inflows and outflows on financial statements. A company paying $100,000 for a truck expected to last 10 years, for instance, might “pretend” to pay for that truck in “accrual” expenses of $10,000 per year over 10 years. Or a magazine company getting paid all at once for a three-year subscription would have to likewise “pretend” to record the revenue over three years, to match the life of the subscription, even though it already received the cash. Accruals sound logical, but academic research has found that companies often abuse them, so many analysts undo them, creating free cash flow – a “cash” version of earnings. In fact, one purpose of the statement of cash flows is to show just cash in and out; it reverses many accruals following official standards. Confusingly, sometimes companies offer their own version of free cash flow to “help” investors and analysts, but not surprisingly this attempt to undo the abuse-prone accrual system is, too, allegedly being abused. It’s all about motivation, basically |

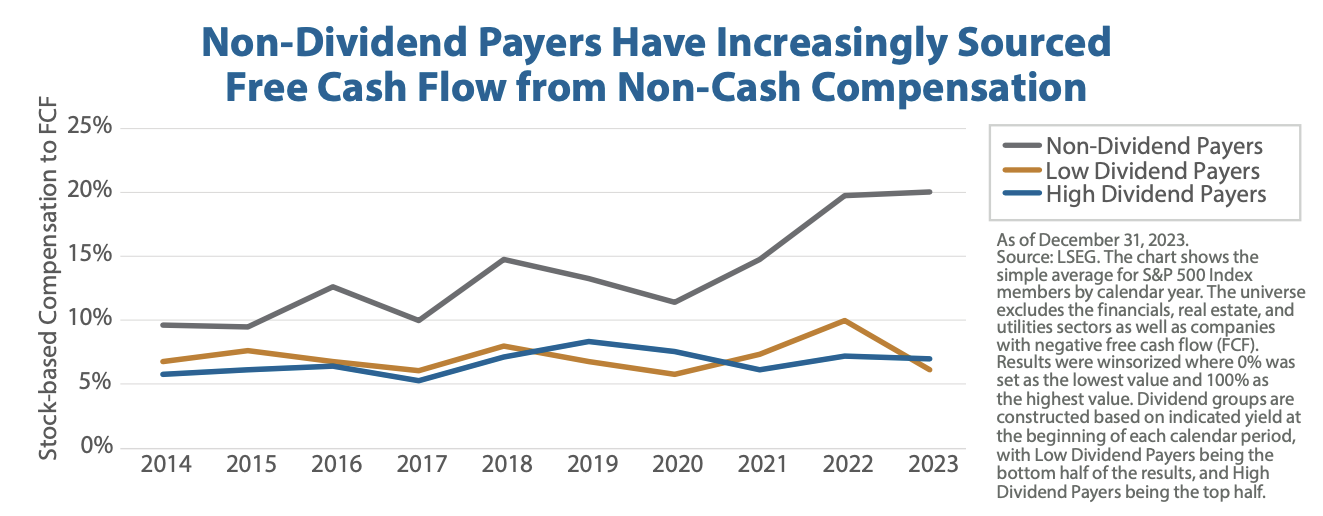

The thrust of the Miller/Howard paper is that dividend payers are good, because they’ve just been doing their thing, unloved as they may be. But non-dividend payers, per the above chart, have been turning more and more to stock-based compensation (SBC), and SBC, as a non-cash expense on the income statement (FASB doesn’t allow line itemization of it on the income statement, but it’s in there). And when SBC gets subtracted out of net income on the statement of cash flows, free cash flow (at least derived in that way) looks larger, by something like 20% in many cases.

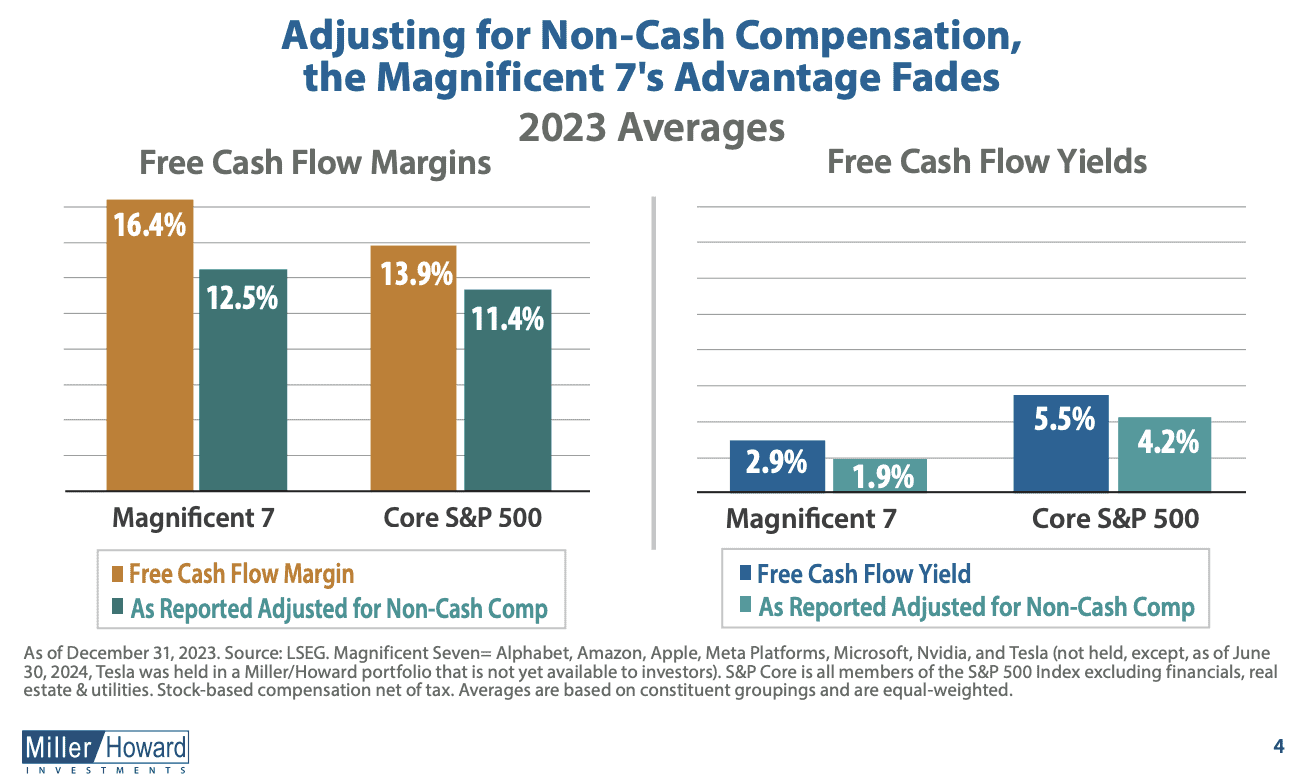

And if you turn free cash flow (FCF) into a valuation metric – free cash flow yield, which is basically the same as dividend yield but with FCF substituted (higher means a cheaper valuation) – the higher incremental use of SBC means the Magnificent 7 are even more expensive than appears (if SBC effects are removed). See the right-hand chart:

Is Miller/Howard right or wrong?

Now, if someone hired me to shoot down the Miller/Howard paper, the first thing I’d point out is that SBC costs are already included in earnings. The Mag 7 folks aren’t really hiding anything. It’s just when the enterprising fundamental analyst goes to adjust, the increased SBC makes FCF look “too good” in a sense, if that analyst is not noticing SBC any other way.

But even if they should be, I’d guess that many of the people buying the Magnificent 7 are not buying for reasons of current free cash flow. Some may not even understand what it is.

Also, with rising share prices, SBC is axiomatically going to increase unless a company downgrades its compensation policies – this effect may be partly an artifact of rising stock prices post-COVID.

So the critique might be that this paper has the slight feeling of being written with an agenda by someone who really wants to plug dividend stocks.

Miller/Howard loves dividends

Even if the methodology is at times intellectually thin, the Miller/Howard conclusion is something I fully agree with.

“The high and growing levels of stock-based executive compensation create misleading comparisons with non-dividend-paying stocks. Once non-cash executive compensation is adjusted out, stocks with higher dividend yields are actually superior on both free cash flow margins and free cash flow yields.”

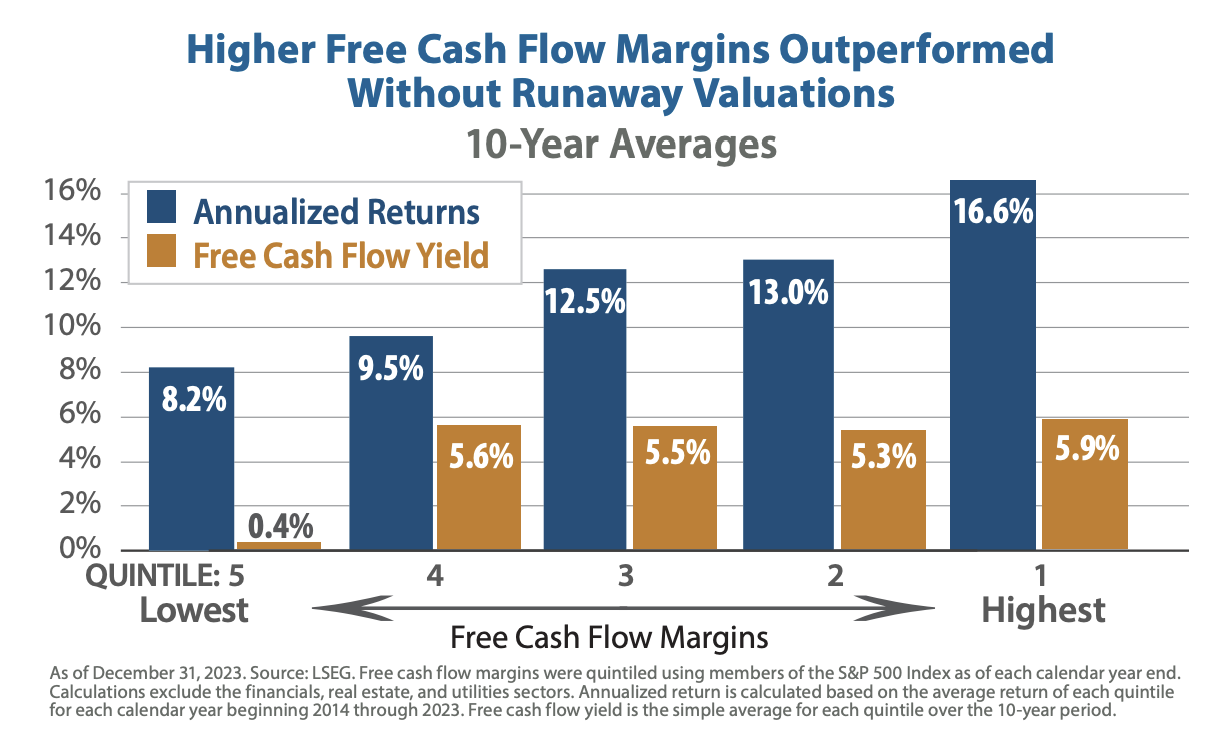

Ultra-low rates post-2009 wrecked the normal laws of investing physics, and financially healthy stocks – many of which paid dividends – took a back seat to low- or non-yielding companies. Now FCF yield is more like a potential dividend yield, but as M/H points out, even during the past 10 years – mostly a weird time – companies with high FCF yield did much better than those not earning much in cash flow.

Note that the middle segments are a bit odd; the relationship is nonlinear, or at least was in the past decade:

What’s the takeaway?

Despite my quibbles (one more! M/H discusses buybacks vs. dividends without mentioning the tax advantage of buybacks), I think M/H is dead on the money in that we’re likely entering a more normal market phase – that is, whenever the AI hype dies down – that will favor cash-generating companies all over again.

And cash generation never really goes out of style: The above graphic shows the power of generating a lot of cash relative to share price even in an ultra-low rate economy that appeared to give all the love to early stage biotechs and tech companies with no profits.

As a bonus, for whatever economic civic-mindedness matters, I believe that investing in financially healthy (and responsible) companies is good for the overall economy – it rewards good corporate behavior. The investing world loves growth, and managers are often compensated based on company growth. Having the discipline to not spend money on internal/external growth initiatives and instead return it to shareholders signals a degree of responsibility.

But that said, it’s still about motivation. As with the tweaking of FCF discussed earlier, some companies know analysts like me say pro-dividend things like this, and try to look the part without actually being the part: They go out and borrow money to pay dividends, which is a no-no.

I’ll cover my strategies for finding good dividend stocks in a future article.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.