News Roundup: American Productivity Rocks, Trump Trades, Dividends Good or Bad?

American productivity reigns supreme

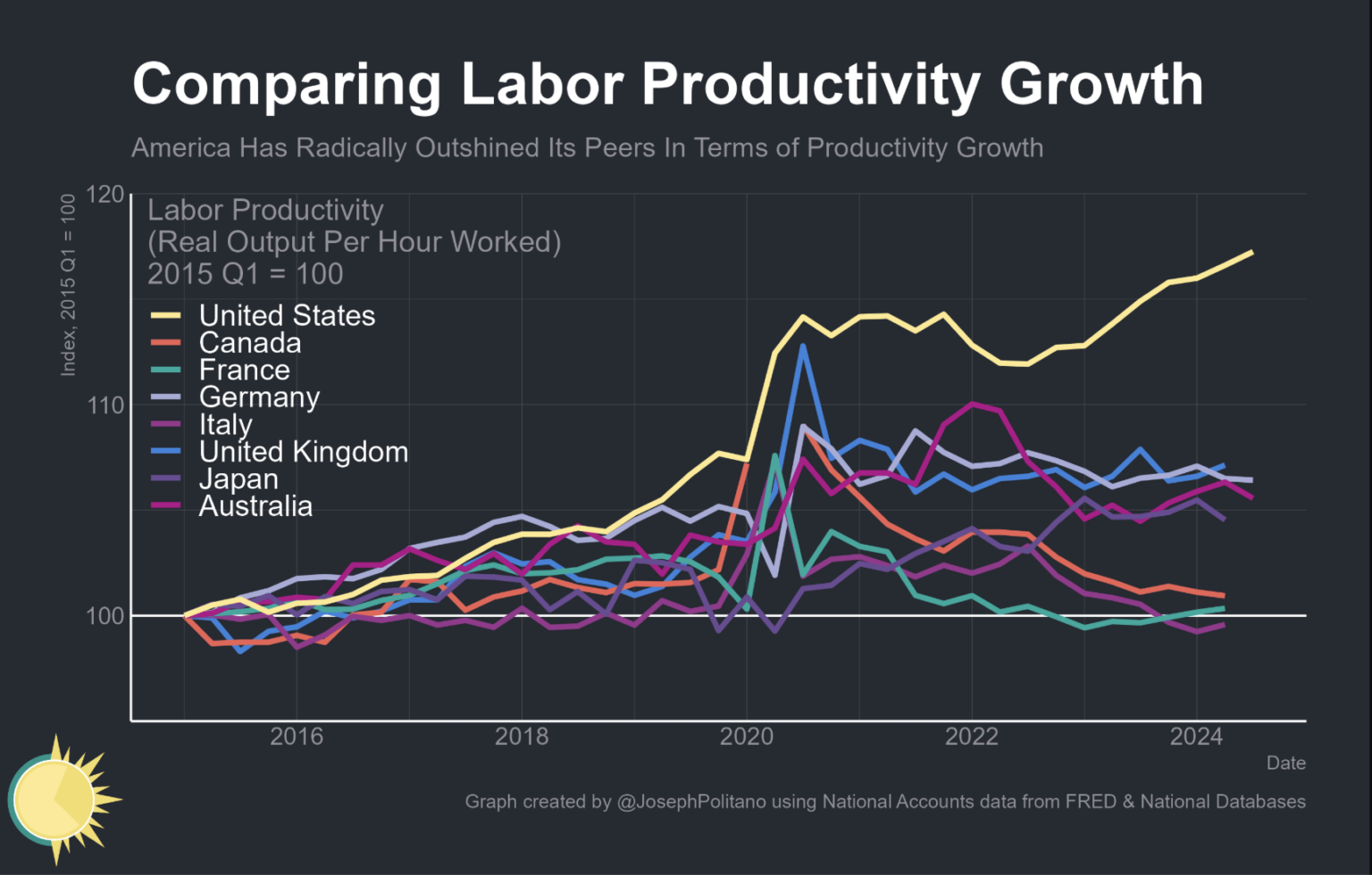

Claudia Sahm, former US Federal Reserve economist and creator of the Sahm Rule (and friend of BBAE – we’ve interviewed her here) put out both a Bloomberg article and blog post about how amazing US productivity is, relatively speaking – a legitimate factor in at least partially justifying US stock valuations that are relatively high.

Interestingly, a few years before COVID, US productivity (yellow line below) was middle-of-the-pack. Ironically, it spiked just before and in the early days of COVID, and has risen after a 2022 dip.

Why?

Claudia pegs two factors: a strong US job market and lots of new businesses started in the US, partially thanks to COVID-era stimulus plans.

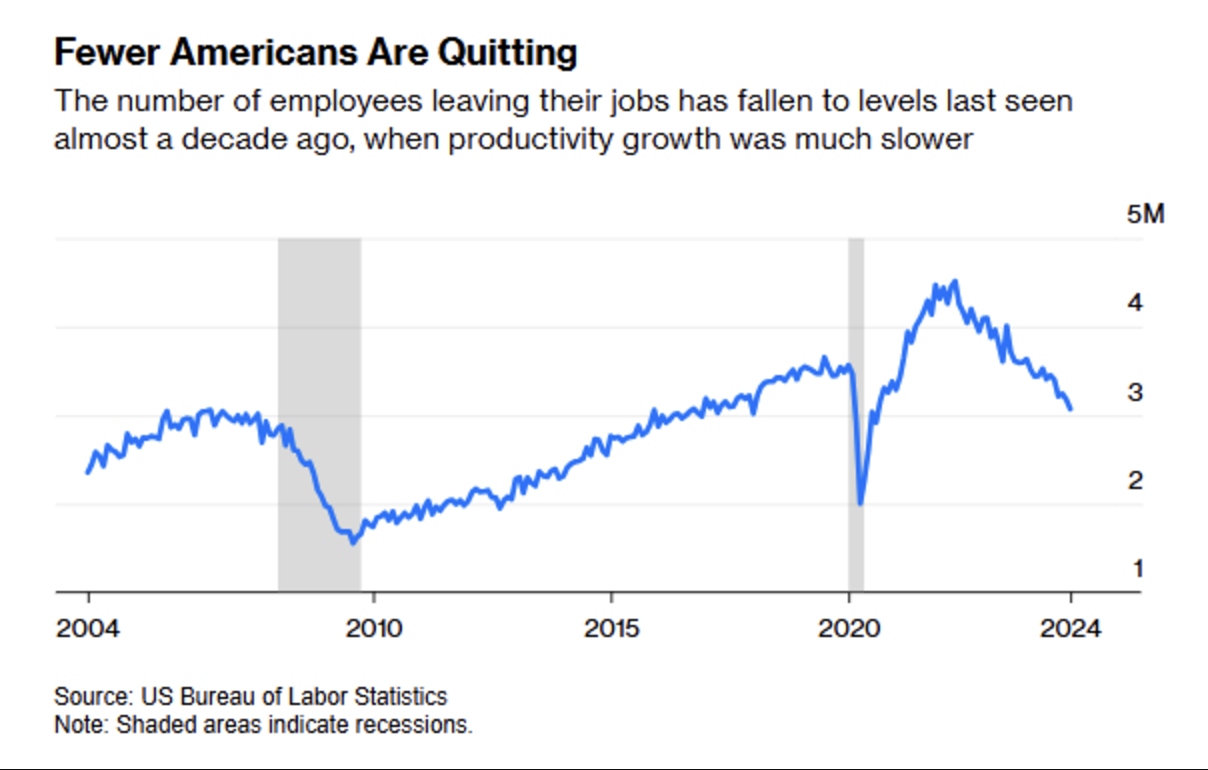

Here’s a chart from Claudia’s Bloomberg article showing more Americans staying in the workforce:

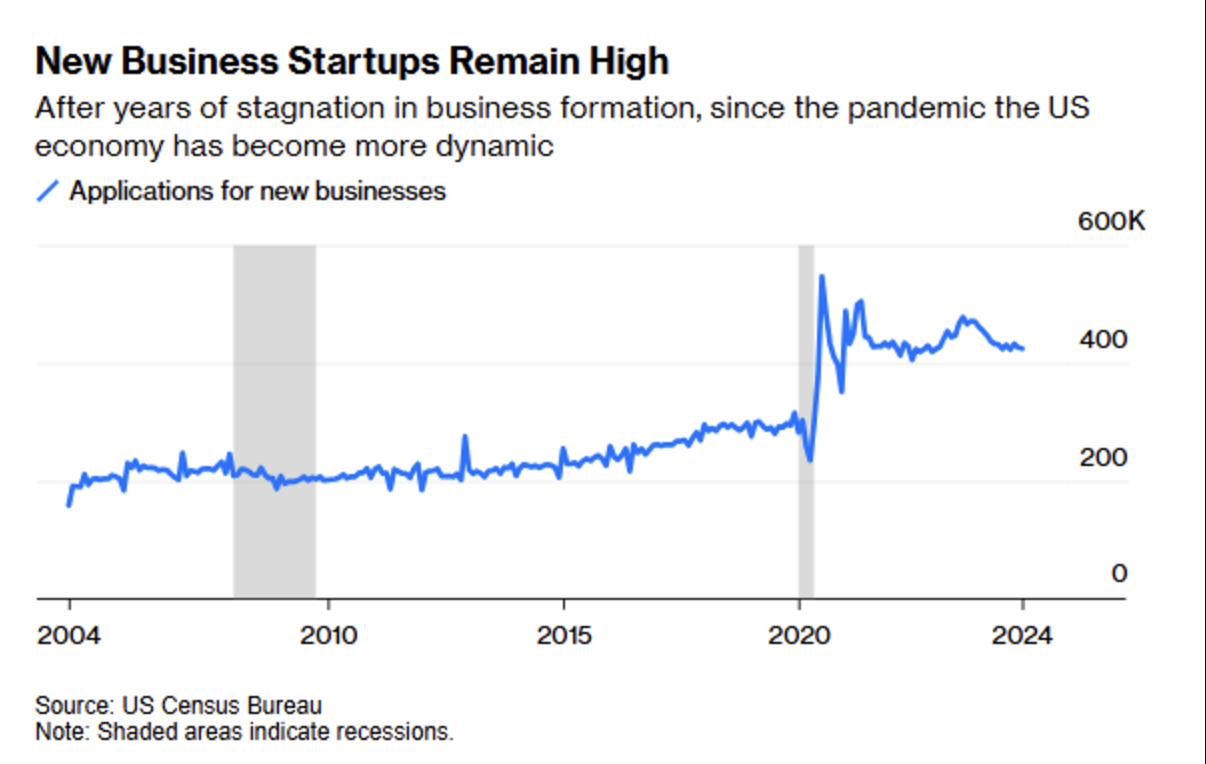

Second, the pandemic got Americans starting businesses like there was no tomorrow – and for whatever reason, the level of new business applications has remained high.

What does this mean for investors? New business startups are not going to be public companies, but the general trend of relatively higher US productivity helps to partially justify relatively higher US equity valuations: The S&P 500’s P/E ratio is 27.8, compared to 19.9 for the UK FTSE 100, 16.5 for Japan’s Nikkei 225, and 14 for China’s Shanghai composite.

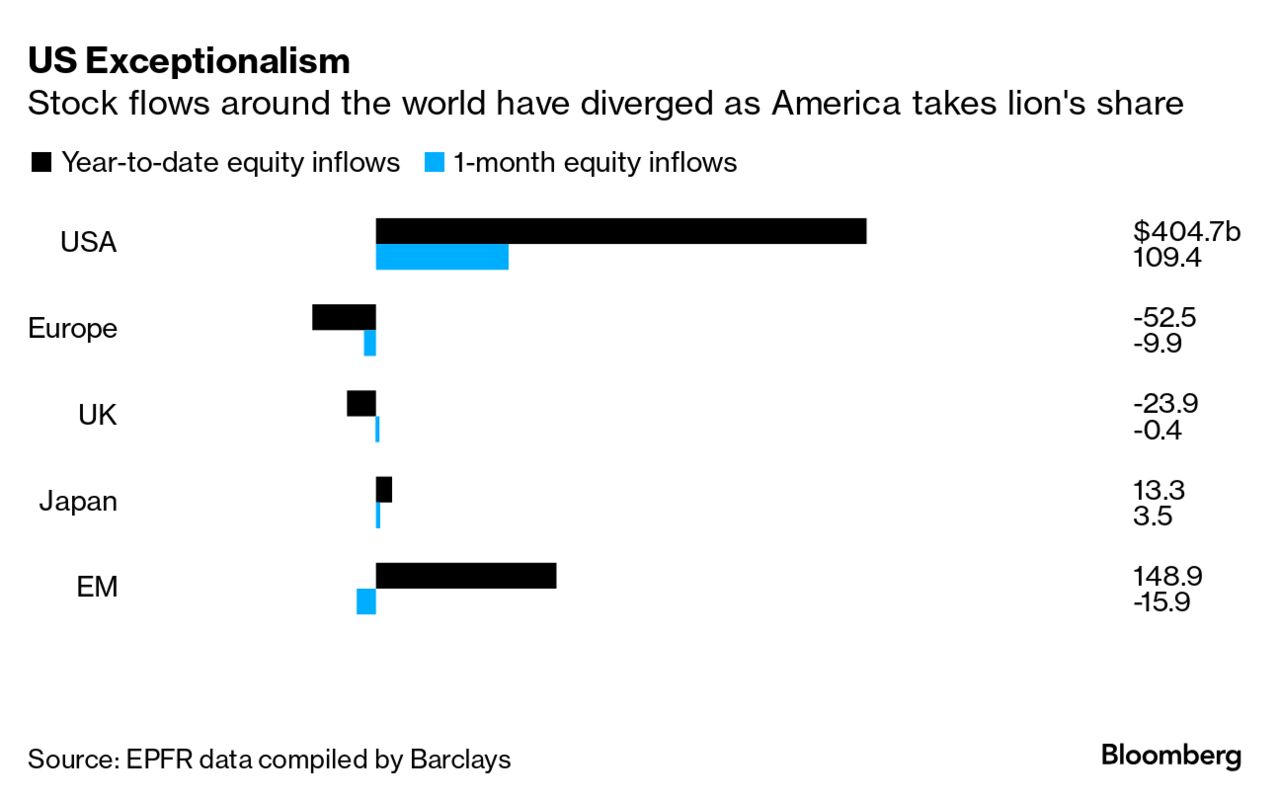

And not surprisingly, it means more money has been flowing into US markets, as this Bloomberg graph shows.

Bloomberg found that 10 years ago, the US market was 50% of the world’s market cap. “Everyone” back then assumed that the rest of the world would grow – their markets were incipient with much runway. But in fact, the opposite happened: Now the US is ⅔ of global market cap.

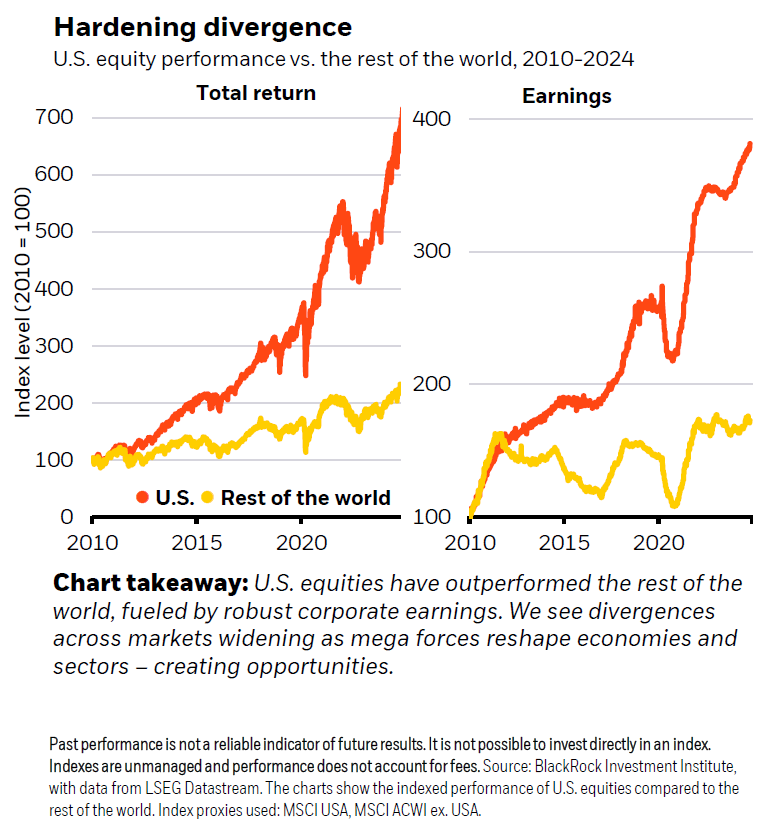

Here’s one more chart of the S&P 500 relative to “everything else” for the past 14 years, showing that it’s not just a valuation thing: US companies are simply out-earning their global peers.

“Trump Trades” softer this second time

Alf Peccatiello of The Macro Compass compared some of the known Trump Trades this go-round versus after Trump was elected in 2016.

The small print on Alf’s chart below isn’t ideal, but the blue line shows various comparison trades from election time to six months after. The red line shows the same trades after the recent election, so it just goes for about a month.

The S&P 500 has moved roughly comparably – recall, though, that just as virtually all the most respected forecasters saw Hillary Clinton winning in a landslide in 2016, many market pundits expected markets to crash following a 2016 Trump victory. Neither happened.

Banks and small caps have shot up both times, albeit to a lesser extent recently. Banks do well with less regulation, and small caps do well with a stronger domestic economy.

Investors bailed out of 10-year bonds both times, though notably less so lately. The bond market does not have faith in Trump’s plan to reduce inflation; in fact, it’s betting on the opposite happening: that Trump’s high government spending, tax cuts, deportation of cheap labor, and tariffs will cause inflation. Inflation makes the “fixed” coupon payments that bondholders receive worth a bit less, so the bond market is selling off bonds in anticipation.

Currency markets also seem to disbelieve Trump’s plan to weaken the US dollar, as the US dollar strengthened versus the Japanese yen and Mexican peso, but far less than in 2016.

The exception to a softer set of Trump Trades: Bitcoin has been a huge winner so far. Unlike bond and currency investors, who doubt Trump’s policy effectiveness enough to bet against it, cryptocurrency investors believe that Trump will be a pro-crypto president.

Dividends: good or bad?

I often emphasize that economics (and investing, which is a subset) is a social science, albeit one masquerading as a mathematical science. We can observe, describe, and analyze phenomena with numbers, but the root cause of things happening is human beings making decisions.

A curious, but incredibly common, byproduct of this is that unlike in “hard” sciences like physics and chemistry, where, if done correctly, your kid’s science fair experiment on gravity or mixing baking soda and vinegar will likely match mine’s – assuming they’re all done correctly – different studies in soft sciences yield totally different results.

Graphic-maker Ryan from StreetSmarts may have downgraded his frequency to weekly, but he’s got an interesting piece on the futility of dividends. It’s based – and pay attention here – on the past 10 years.

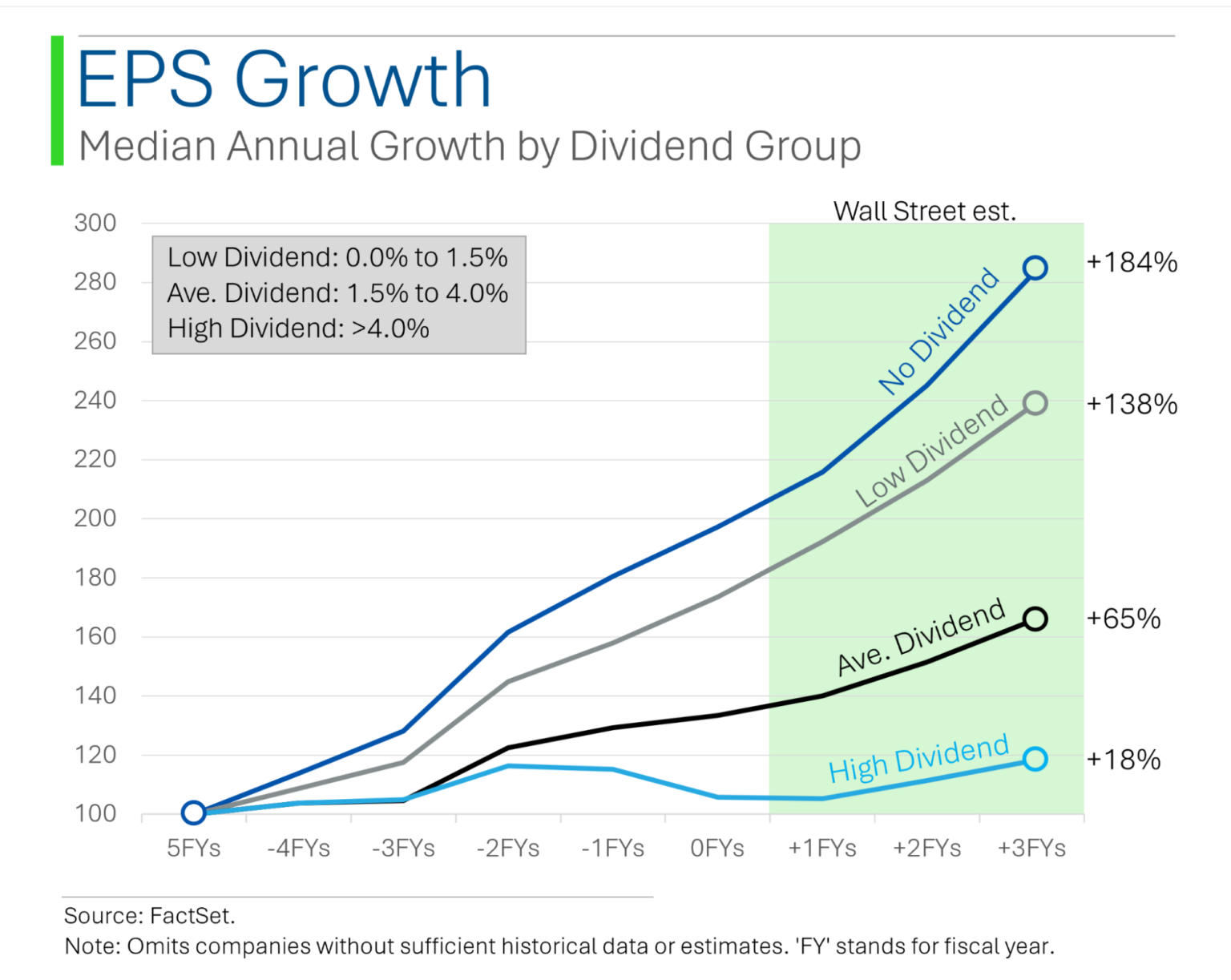

The graph below divides stocks by dividend yield (“high” is above 4% in this sample, and “low” is 1.5% or below; the S&P 500 has a 1.32% aggregate dividend yield at present for comparison).

Ryan admits his bias as a growth investor. As a Gen Xer, I’ve noticed that younger Millennials and Gen Z investors tend to favor growth stocks; part of this has always been true, in that younger investors have more time and thus structurally higher risk tolerances, but I believe part is a function of the ultra-low-rate investing environment in which they grew up: Extremely low rates and strong economies favor growth stocks, so it’s understandable for these investors to conclude that stock investing = growth stock investing for anyone who wants to make real money. That’s how the world they know has worked.

Anyway, Ryan shows that according to stereotype, the no-dividend stocks had (and are expected to have*) the highest earnings growth over an eight-year period.

*Ryan looks at the past five years of actual numbers and then mashes it up with the estimated next three years. This might add a little Wall Street bias, but it’s clear that the trends in the actual numbers were tracking according to plan already.

I do not doubt Ryan’s data. What’s funny about this to me is that a study in 2003 by Cliff Asness (of AQR Capital Management; Cliff famously studied momentum as a factor in academia before it was cool) and Rob Arnott found the exact opposite thing.

In Surprise! Higher Dividends = Higher Earnings Growth, Arnott and Asness found that stocks with the highest dividends had the highest earnings growth over the next 10 years.

Who’s right? They both are. Welcome to the social sciences.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.