I asked this question in my latest Forbes article.

My piece was a little long, but I believe the underlying question is important to society and not going away: Should companies stand for certain values?

Survey data looks mixed: A Gartner survey of 30,000 employees found that 87% of them believe companies should take stances on social issues directly related to their business, and 74% say that companies should take stances on social issues not directly related to their business.

To me, 74% feels like a big number, but apparently 96% of Gen Zs say that companies should be involved in solving social issues, which seems to loosely match.

Then we have a Wall Street Journal-University of Chicago survey of 1,019 adults that found that only 36% of respondents said companies should take stances on issues outside their business scope, whereas 63% said companies should not.

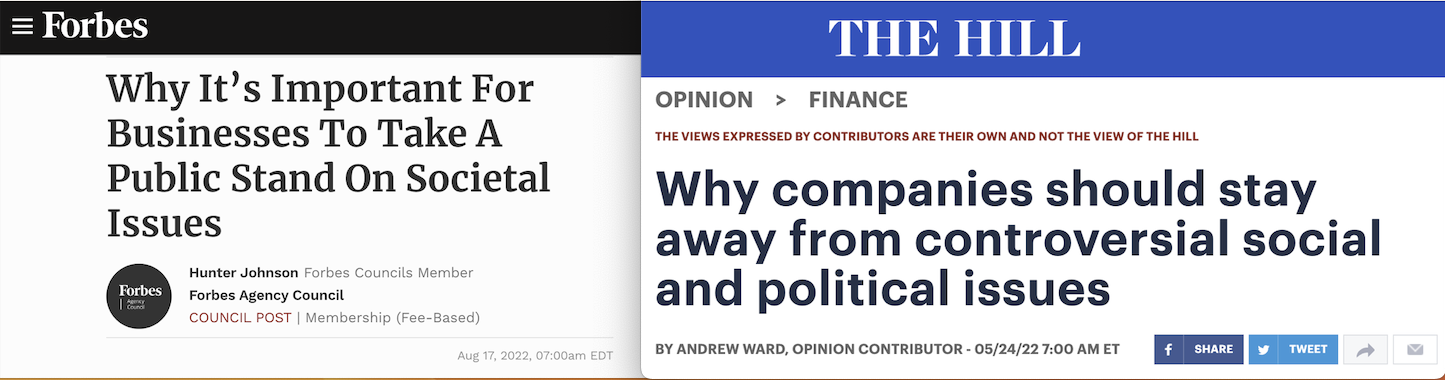

Headlines from the internet – in this case TheHill and Forbes websites – are divided:

Does ESG Investing Work?

I tend to think that people don’t always know exactly what they want. And even then, wanting something doesn’t make it workable in practice: ESG, for instance, has taken a lot of heat in the past year or so for various issues, as I wrote in the article:

- Fakery: 60% of executives said their organizations were exaggerating sustainability efforts, per a Harris Poll in January.

- Hypocrisy: Citigroup and The EU Platform on Sustainable Finance once considered defense stocks non-ESG until Russia invaded Ukraine, at which point they reconsidered, giving the impression that guns are bad for everyone else, but they’re suddenly OK when they’re used to defend me.

- Confusion and inconsistency: Tesla got booted from the S&P ESG Index while ExxonMobil remained; meanwhile, the three credit ratings agencies issue ratings with a 0.99 correlation – so close that having three agencies seems redundant – while the patchwork quilt of ESG ratings agencies has the opposite problem: a 0.30 correlation. A concept needs clarity to be workable, and nobody seems to agree on what’s either “good” (old-style ESG) or “risky according to ESG factors” (new style).

- Cable-bundle problem: Shoving “E” and “S” and “G” together may not always make sense, as different investors may have different priorities, definitions, and standards. The problem compounds when you try to put ESG stocks into ESG funds to be sold to ESG investors.

That doesn’t mean that companies can’t make the world better: Intel, for example, moved ahead of governments in cleaning up conflict minerals in the semiconductor supply chain. Government in Congo didn’t have the capacity to stop warlords from using child soldiers, so Intel led the way in what later became a business school case study. Intel’s own standards both preceded and exceeded the Dodd-Frank standards which came later.

There’s also the notion that because companies can create negative consequences outside their primary business orbits, companies should have some awareness of and responsibility for things outside their primary business orbits. For years, and in fact centuries, companies have offloaded “costs” (sometimes literal costs, but often suffering or damage) onto the bystanding world through things like environmental damage, child labor, or misuse of customer data. Even if regulation is the main way to fix this, it doesn’t seem like a stretch to expect companies to consider how their profit-seeking actions may affect society and the world.

For both of these reasons – removing the bad and promoting the good – the public has embraced ESG, or at least the appealing idea of using one’s investment capital to do some good in the world.

This sounds wonderful on the surface. In fact, I really love this idea, too.

But inside are some difficult questions.

Should Companies “Take A Stand and Speak Out” on Social Issues?

The first is: What’s “good?” (Incidentally, note that much of the ESG industry has moved away from channeling money toward “good” things in favor of channeling it away from ESG risk exposure – a coat factory in a low-lying coastal area employing formerly exploited women might score highly on the Social factor, but poorly on the Environmental one, because it’s exposed to sea level rises.)

And even if we know the direction of “good,” how fast should a company move in that direction? And then there’s the endpoint, if one exists: What’s good enough, and what’s going too far?

It’s easy to forget that societies and societal preferences are constantly evolving, too, even if, like a parent with a young child, it happens too gradually for us to notice until we see the marks on the wall.

If societal preferences are such that consumers and employees and perhaps some investors all want it, it’s fully possible for a company to do well while doing good.

Picture a fair-trade coffee company. Its coffee costs more, but that’s on purpose because the company isn’t just selling good-tasting coffee: It’s selling good-tasting coffee that does a small bit to help the living standards of coffee pickers who would presumably live unreasonably meagerly in a purely free market. Assuming enough customers want that – and for an inexpensive thing like coffee, there’s probably enough that do – the company, its customers, and probably many of its employees and investors are in copacetic alignment. Shareholder primacy.

But what’s the responsibility of more “regular” companies that aren’t directly aligned with a cause as part of their DNA?

It’s easy to see a case for keeping up with societal norms: If a company’s employees, customers, investors, and board members all (or mostly) agree that regardless of the company’s line of business, reducing energy wastage and organizing soup kitchen efforts in local communities are good things to do, and see that most other companies are doing similar things, or more, then a company probably needs to do stuff like that, too, to not fall out of favor with employees, customers, board members, and possibly investors.

It’s stickier for a company to take a stance on a divisive issue outside a company’s scope of business like abortion or immigration.

Companies could, and some have, and it appears likely that passionate factions both within and outside the company will increasingly pressure companies to “speak out” on contentious issues, but this can be like playing heavy metal or gangster rap in the elevator instead of elevator music: It delights some and alienates others.

The questions, then, may be:

- What’s a realistic expectation for a company’s participation in societal “progress?”

- What’s “progress” in a workably broad and clear sense?

- What’s not a realistic expectation?

James

p.s. If you don’t yet have a BBAE account, you have many reasons to open one (no social causes required!) – just click here to have a look at the cash reward you’ll get when you open one.