Trump Tariffs: Will They Work? Will They Happen?

“Give us a protective tariff and we will have the greatest nation on Earth.”

-Abraham Lincoln

If you’ve seen any economic news recently, you’ve likely seen the word tariff.

President-elect Donald Trump, who has called tariff “The most beautiful word in the dictionary” had threatened between a 10% and 20% across-the-board import tariff on “Day 1” during his campaign, and a 60% tariff on Chinese imports. That seems to have morphed to a proposed 25% tariff on Mexican and Canadian imports and an extra 10% tariff on Chinese imports, on top of standard tariffs in place.

Trump seems really into tariffs. Why?

Trump has said he believes tariffs will reduce the US trade deficit by bringing more sourcing into the US, and also sees them as retaliatory measures for China, Canada, and Mexico – which together supply about 20% of US imports – for not doing enough to stop both fentanyl and illegal immigration (in the case of Canada and Mexico) from coming into the US.

Additionally, Trump has threatened supplemental tariffs on EVs and a 100% tariff on imports from BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) if they try to replace the dollar in BRICS-related trade.

What does all this tariff talk mean? Specifically, what might it mean for investors? A full examination would span multiple books, so let’s take an article-length tour of tariffs. While tariffs are an issue that straddle economics and politics, we’ll stay in the non-partisan economic analysis camp.

Economists agree that Lincoln was wrong: tariffs don’t work

Depending on the study, either 0% of economists say tariffs work, or just a few do.

Wikipedia isn’t my usual go-to for formal citations, but its page on tariffs sums up the economic view:

“There is near unanimous consensus among economists that tariffs are self-defeating and have a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth.”

So if tariffs don’t work, why are we even discussing them?

Well, let’s define “work.” There’s no question that division of labor and Ricardian economics enrich the world by increasing sourcing options, spreading out value creating and, like any good market, best matching suppliers and demanders of things.

Rather than each country becoming a standalone “one-stop-shop” for producing and consuming things – in which case, for example, Icelanders get to choose between, say, pickled herring and pickled shark – tropical countries rich in fruit yet poor in things pickled can trade. A country with highly educated, expensive labor can trade high-end products, IP, and skilled services with a low-labor-cost country rich in agriculture. Both win.

It’s easy to see that in a broad sense, tariffs – which are essentially trade taxes paid by importers and remitted to governments – impair global collaboration. From a game theory perspective, tariffs slow global economic progress.

Sometimes, you want that. Or at least it’s a tolerable side effect of pursuing non-economic trade ends: For obvious reasons, Good Guy Country won’t want to depend on buying weapons from Bad Guy Country, for instance, even if it makes economic sense on paper. While such a situation would call for more than tariffs, the point is that there are rational reasons to not have totally free trade.

Tariffs vs. sanctions and embargoes

Trade restrictions in the form of embargoes, sanctions, or export/import restrictions may be less effective than intended – the global economy is so interconnected that it’s easy for violaters to violate them – but at least their logic is straightforward: Don’t let certain things get traded.

A tariff is different. It doesn’t stop the trade; it just makes it more expensive. The surprising point for the layman – yet one that economists largely agree on – is that the cost is principally borne by the country levying the tariffs.

Are the benefits worth the costs? It depends.

Tariffs used to bring in 95% of US federal government revenue

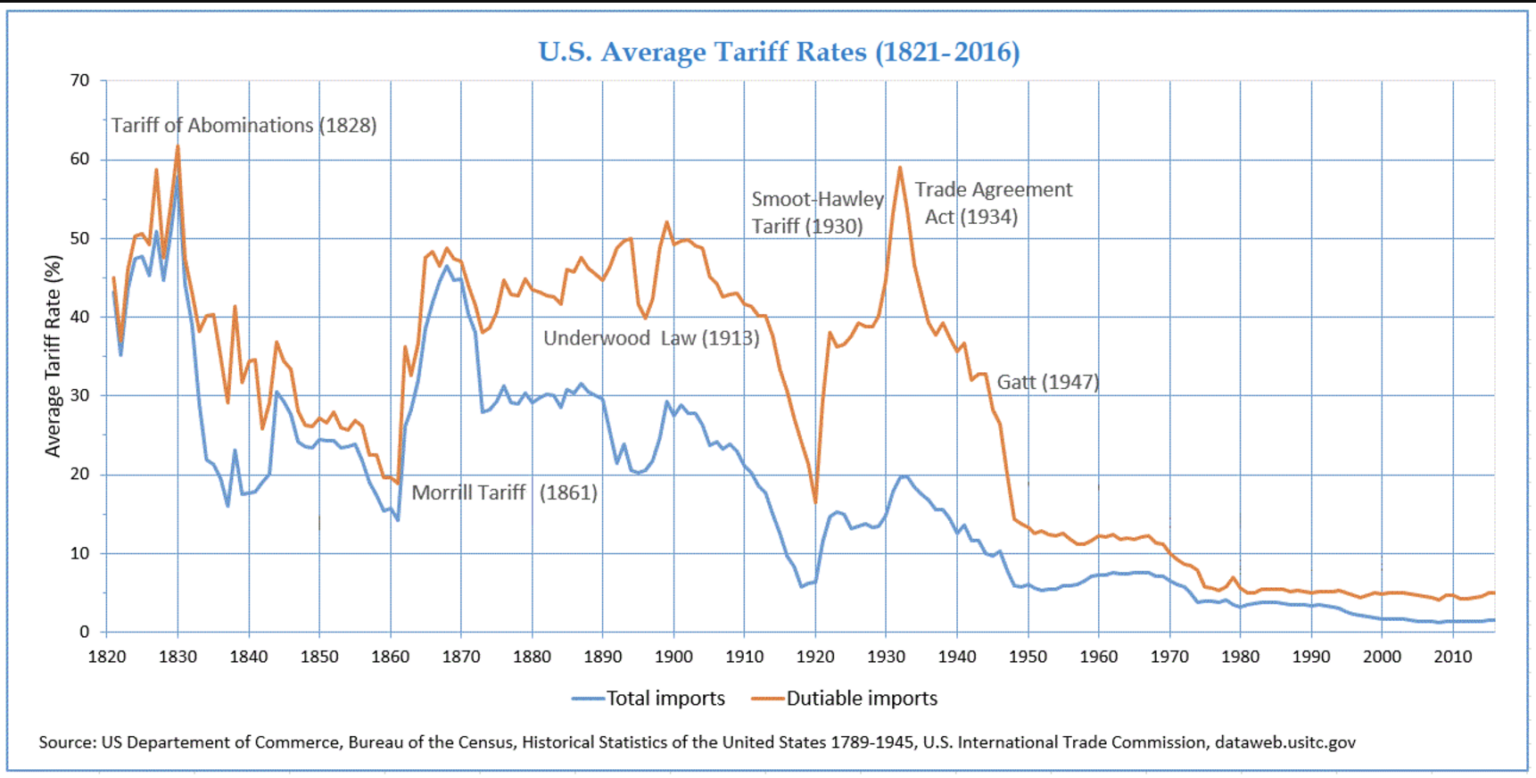

Before income taxes were enacted in 1913, the US government depended on tariffs for revenue, following the Tariff Act of 1789. Tariffs were initially set at 5% of import values, and rose to 40% by 1820.

By the Civil war, the South wanted no national tariffs, whereas President Abraham Lincoln hiked them to 44%. (The Confederate States of America later implemented 15% tariffs to help fund their war efforts.)

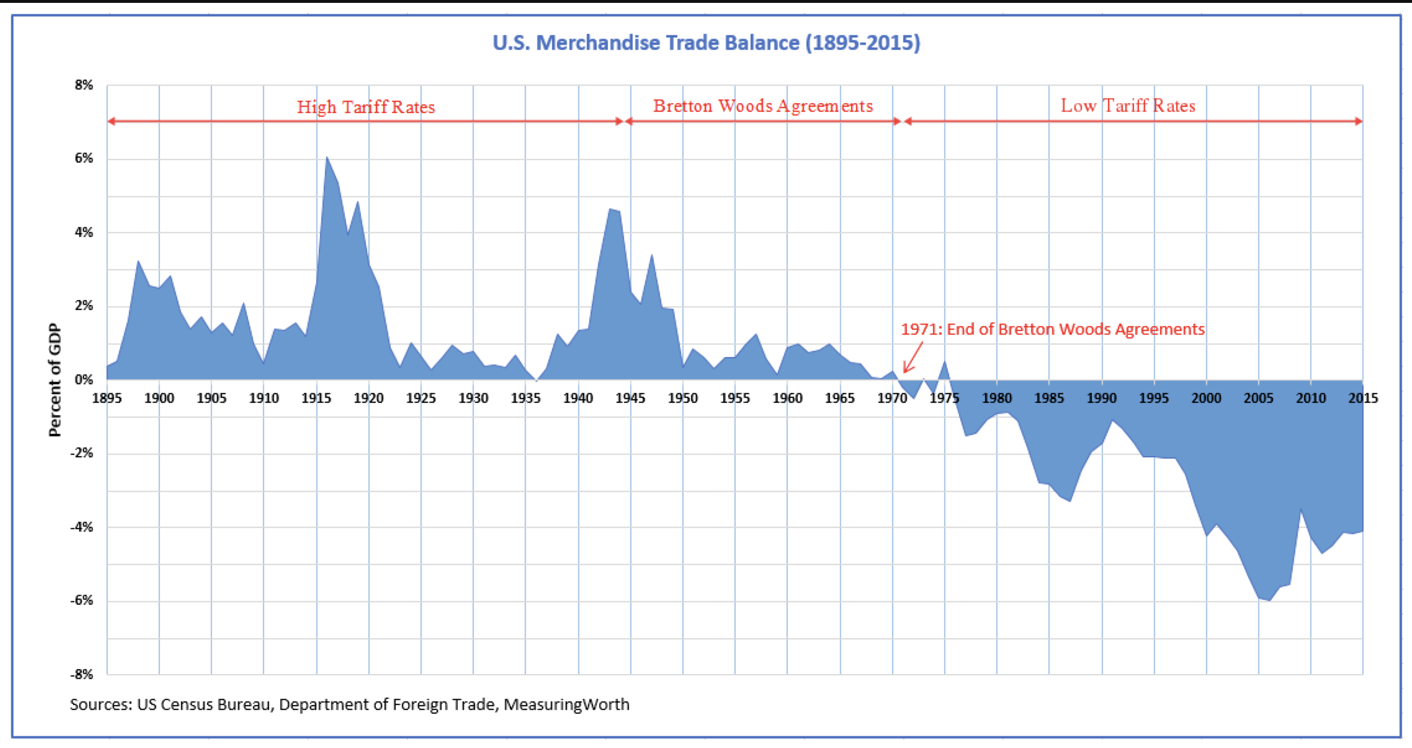

Two charts from Wikipedia below show that higher tariffs correlated with higher balances of trade. Economics is a complicated topic, but it’s fair to say that tariffs did have an effect on trade.

Existing Trump-Biden tariffs

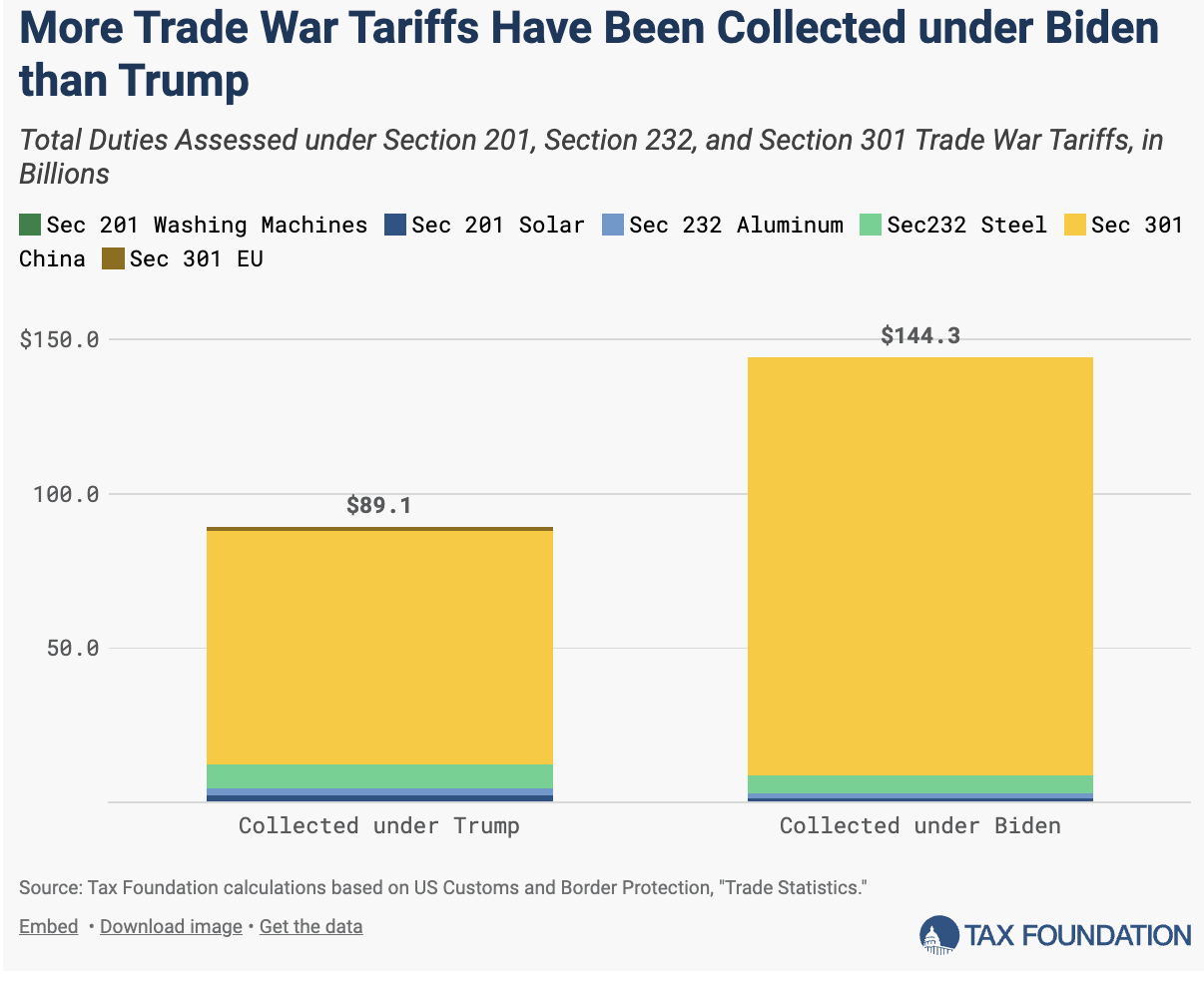

The question, though, is how things net out. For example, the nonpartisan Tax Foundation estimates that the existing Trump-Biden tariffs cost each US household $625 annually, but says this understates the true cost because it doesn’t factor in declines in income, output, and consumer choice from the tariffs.

The Tax Foundation estimates these tariffs will reduce US GDP by 0.2 percent and cost the US 142,000 jobs.

What about Trump’s proposed additional tariffs? The Budget Lab at Yale University estimates an annual cost of $2,421 per US household, whereas the Peterson Institute for International Economics says $2,600.

The Tax Foundation predicts the additional tariffs – if implemented as currently threatened (which they very may well not be, if Trump intends them as starting volleys for negotiation) – would ding US GDP by 0.4 percentage points and cost roughly 345,000 US jobs.

This is because importers – US companies – literally pay the tariffs. For them, the path of least resistance (and maximum profit) is simply passing costs through to American customers.

Sam Ro of Tker.co flagged several news headlines recently that underscore this:

- “Walmart And Lowes Warn That Trump’s Tariffs May Cause Price Hikes” – HuffPost

- “Best Buy says Trump’s tariffs could force it to raise prices for consumers” – CBS

- “‘We Will Pass Those Tariff Costs Back To The Consumer,’ Says CEO Of AutoZone” – Benzinga

- “Craftsman Toolmaker Warns of Price Hikes Over Trump Tariffs” – Bloomberg

Source: Tker.co / Sam Ro

But this doesn’t always happen. Tariffs can reallocate purchasing, though the effect can be more muted.

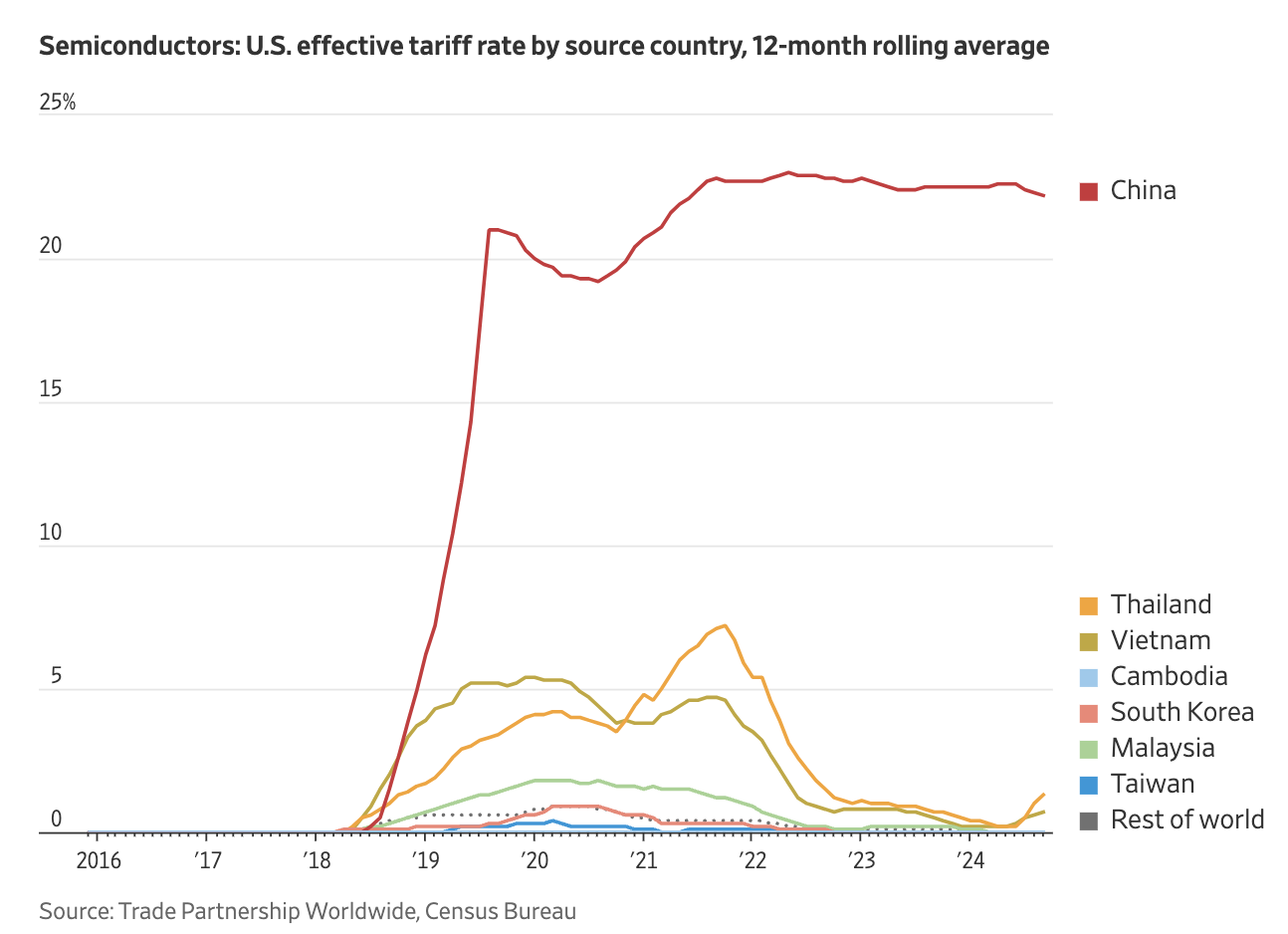

Hannah Miao penned a piece in the The Wall Street Journal (registration or subscription may be required) recently with graphics that illustrate this. See first the spike in semiconductor tariffs as 2019 approached.

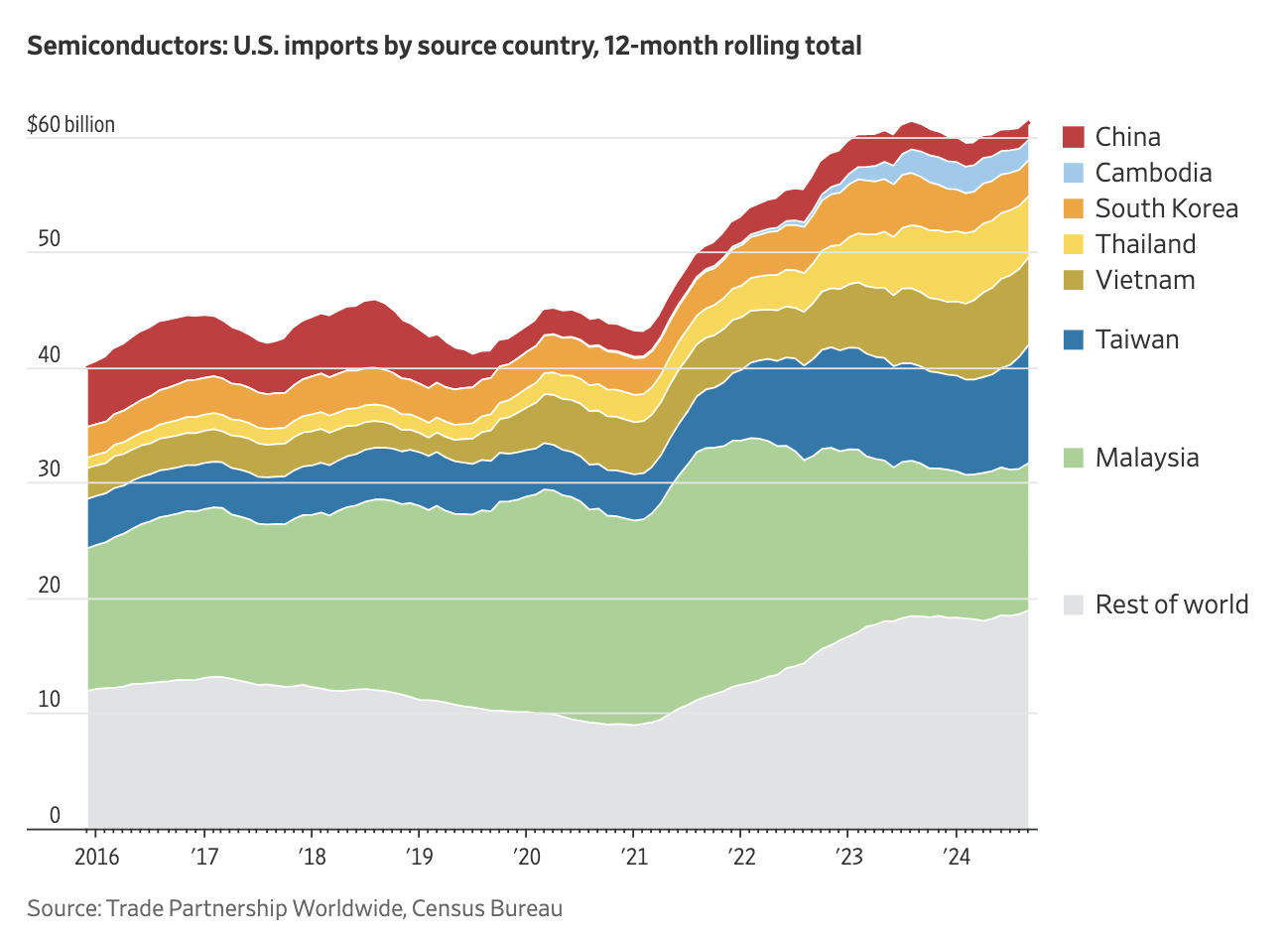

To be fair, the graphic below compiles overall US semiconductor import data, and the dampening of Chinese imports would be more visually pronounced if China-only import data were shown, but we can see that while tariffs of between 20% and 25% did halve, or slightly more than halve, semiconductor imports from China, they didn’t destroy them, and in fact, those imports even grew slightly later on.

It’s complicated, in other words. But tariffs – even if they were mostly at the cost of US end buyers – did reduce demand for Chinese semiconductor imports, and did increase demand for semiconductors from nations more friendly to the US, like Thailand.

Semiconductors are important for consumers and national interest alike, and it’s possible to construct an argument that having the US “pay a little more” for the sake of fostering either greater domestic production capacity (which has been an uphill climb) and/or – and more realistically – a more globally diverse pool of semiconductor providers has at least some logic to it.

The US certainly wishes it has a more diverse network of providers of rare earths now.

What happens next – and what it means for investors

Before looking into the future, let’s remember that so far, the “new” Trump tariffs are simply proposed tariffs at this point. The US’s trade deal with Mexico and Canada is up for renewal in 2026, and Justin Trudeau of Canada and Claudia Scheinbaum of Mexico both appear willing to negotiate.

But if we take the tariff threats at face value, on a company level, we might expect lower profits initially as companies who can front-run tariffs do their best to stock up on inventory ahead of the tariffs. Granted, this should lead to higher profits later because the timing of the purchases are just being toggled, versus the quantity, but for some companies, frontloading could mean higher inventory storage costs.

We can also expect source-shifting by multinationals. Shoe company Steve Madden (Nasdaq: $SHOO) has already announced it will start shifting production from China to Vietnam and Cambodia, for instance. I’d temper this with the caveat that shifting can take many years, depending on the thing being shifted.

We can expect counter-tariffs, and a more tariff-laden world will have slower economic growth than a less-tariffed one. And we can also expect an even stronger US dollar, because tariffs tend to strengthen the currencies of countries implementing them.

A strong dollar is bearish for emerging markets, but at the same time, diversification of global supply chains and manufacturing (making the assumption, based on past tariffs, that manufacturing jobs do not pour into the US following tariffs, but rather sourcing spreads out from high-tariff countries and into lower-tariff countries) is good for exploring companies in specific countries that step in to fill China’s shoes – or Mexico’s shoes, or Canada’s shoes, depending on how and where the tariffs ultimately land.

Speaking of landing, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau very quickly flew to Mar-a-Largo to chat with not-even-President-yet Trump about his contemplated tariffs.

So, perhaps an important distinction is between tariffs and tariff threats.

Economically, tariffs may not work, but does Trudeau’s emergency visit mean Trump’s tariff threats are working? I’ll leave it for you to decide.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.