Weekly Roundup: Rate Cut, Berkshire $1 Trillion, Pandemic Heroes Now (almost) Zeroes

Jerome Powell All But Confirms September Interest Rate Cut

If you’re like me and love mountains, you have to credit the Federal Reserve for having the good taste to hold its annual meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Jackson, where it’s been joked that the billionaires are pushing out the millionaires, may not have a weakening labor market itself, but much of the US does, and so “J-Pow” has decided it’s time to telegraph a September rate cut. As he said in Wyoming:

“The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

…we do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions”

Number of people surprised: 0.

(Although it’s worth noting that the modern Fed’s candor is wildly different from the Alan Greenspan-and-prior era, when the Fed tried hard to be cryptic.)

For the newer investors: What does a cut mean? (Aside from a lower-yielding money market account.)

In a textbook sense – which is often inaccurate in real-life economics because anything obviously “known” gets priced in, leaving surprises to actually drive real price changes – a rate cut should mean higher stock prices, as plunking lower rates into valuation models raises the present value of future cash flows.

Here’s a beginner-friendly explainer video of rate cuts and stock prices from The Plain Bagel.

It should also mean a weaker (i.e., cheaper) US dollar, with the logic that if US bonds don’t pay as much in interest – not an immediate effect of the Fed suggesting a lower Fed Funds rate, but presumably an eventual one – foreign investors will buy fewer of them, which means less foreign money attempting to “buy” US dollars (i.e., demand).

(Again this is economics, and not physics; a stronger US dollar actually followed the rate cuts of 2009, presumably because the world was in crisis and the US, rate-cutting or not, was still the safest haven for frightened money.)

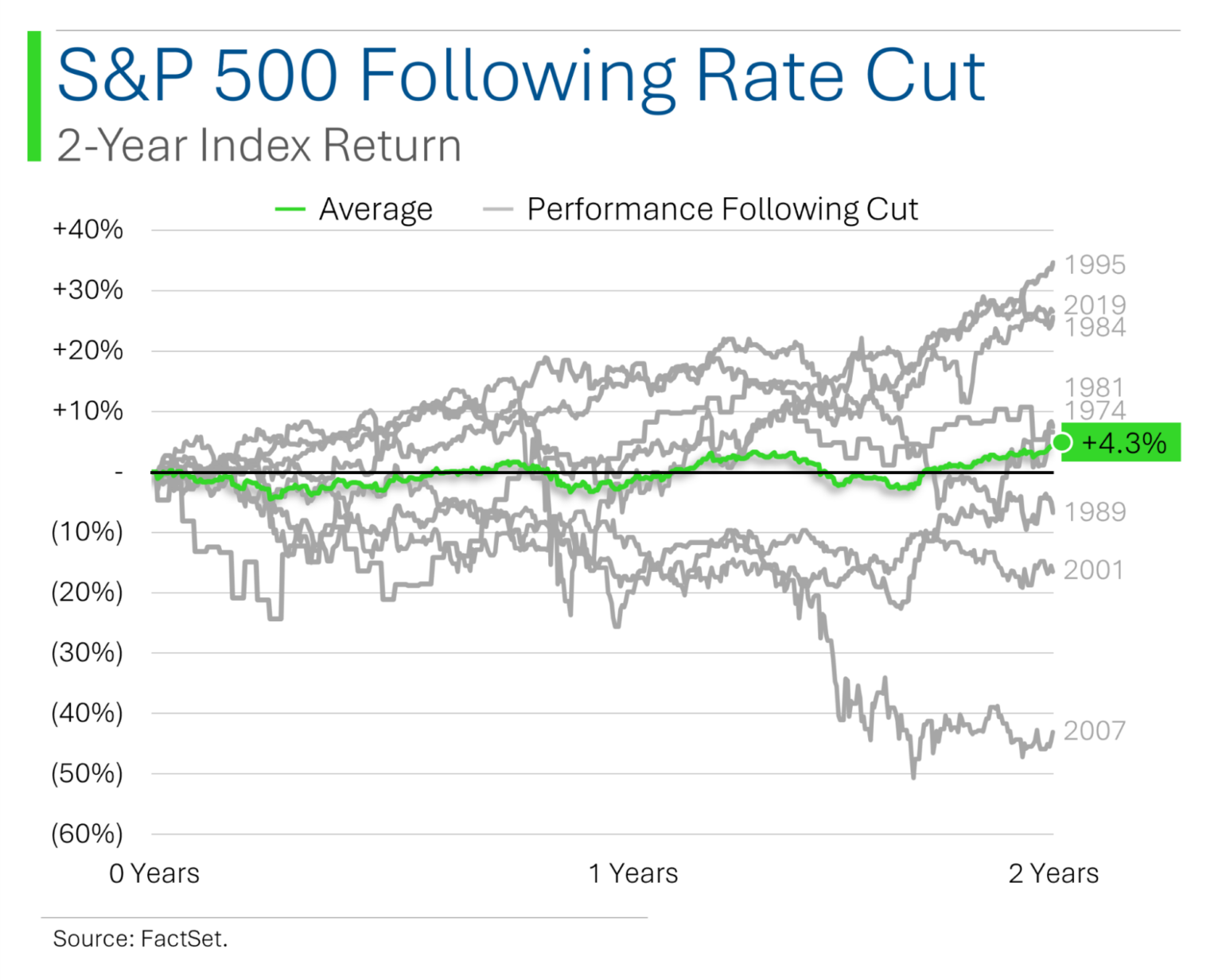

Ryan from MarketLab has a good graphic showing that generally, the two years following rate cuts have averaged out to underwhelming performance, although 2007’s really bad subsequent performance weighs heavily on that average:

A weaker US dollar may be a bummer for your next European vacation, but it’s actually good for US exporters (their stuff looks “cheaper” to foreign buyers) and really bad for emerging markets, which tend to have a lot of debt denominated in US dollars, because few people trust debt denominated in sketchy currencies.

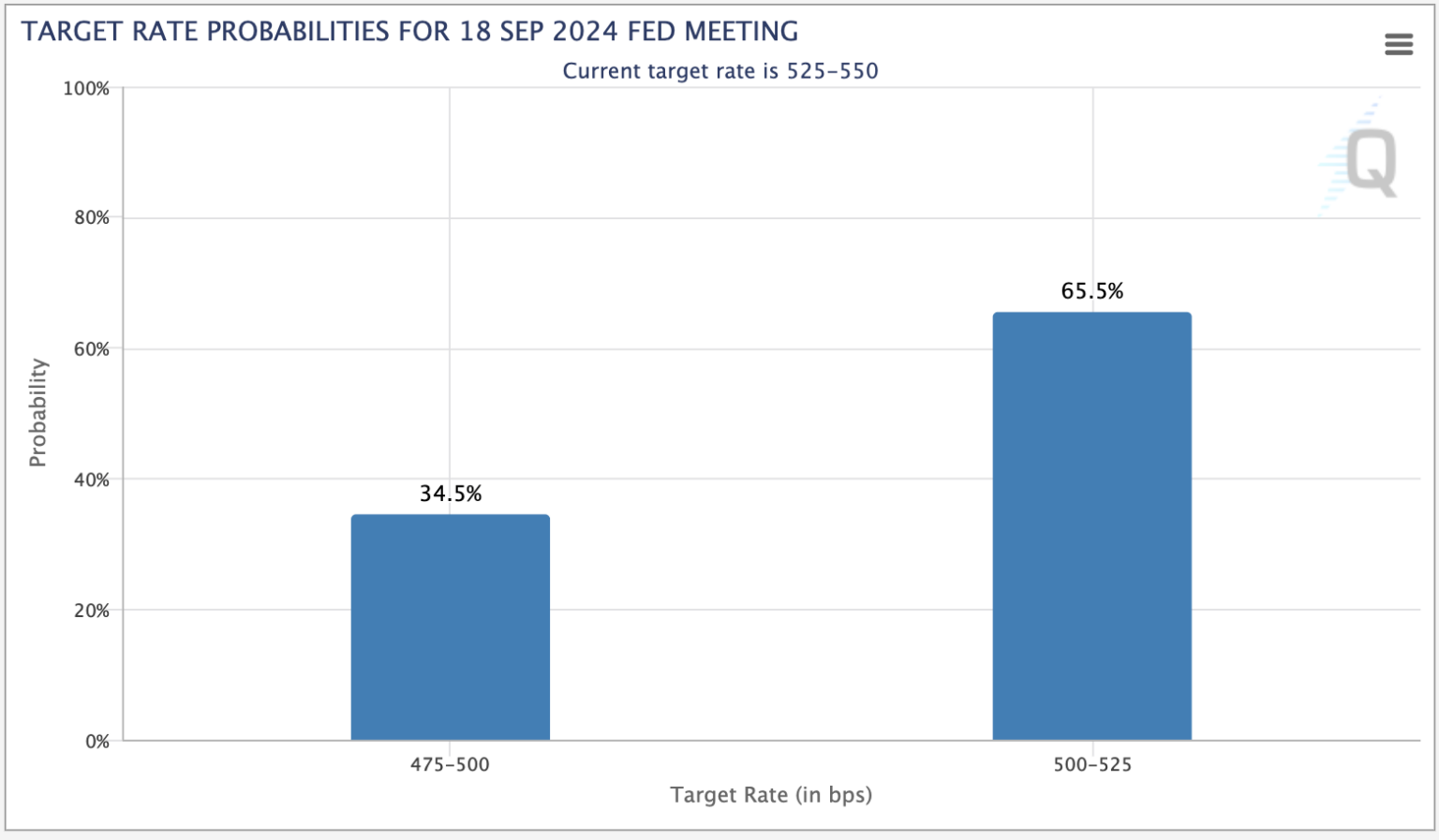

The actual question – the one that embeds enough surprise to move the market – is whether a 25- or 50-basis point cut is coming in September.

The market is currently predicting, roughly speaking, a ⅔ probability of a 25-basis point cut and ⅓ chance of a 50-basis point cut:

So, theoretically, if the Fed cuts by 50 basis points, the market may bump up slightly, and if it just cuts by 25, stocks may remain flat to down a teeny tiny bit.

But if you’re an individual investor and a meaningful part of your portfolio hinges on this kind of detail, I’m going to come out and say that you’re probably investing the wrong way, amigo, and now’s a great time to read up on the benefits of long-term investing.

Pandemic Stocks: Where Are They Now? Plus a Corporate Finance Lesson

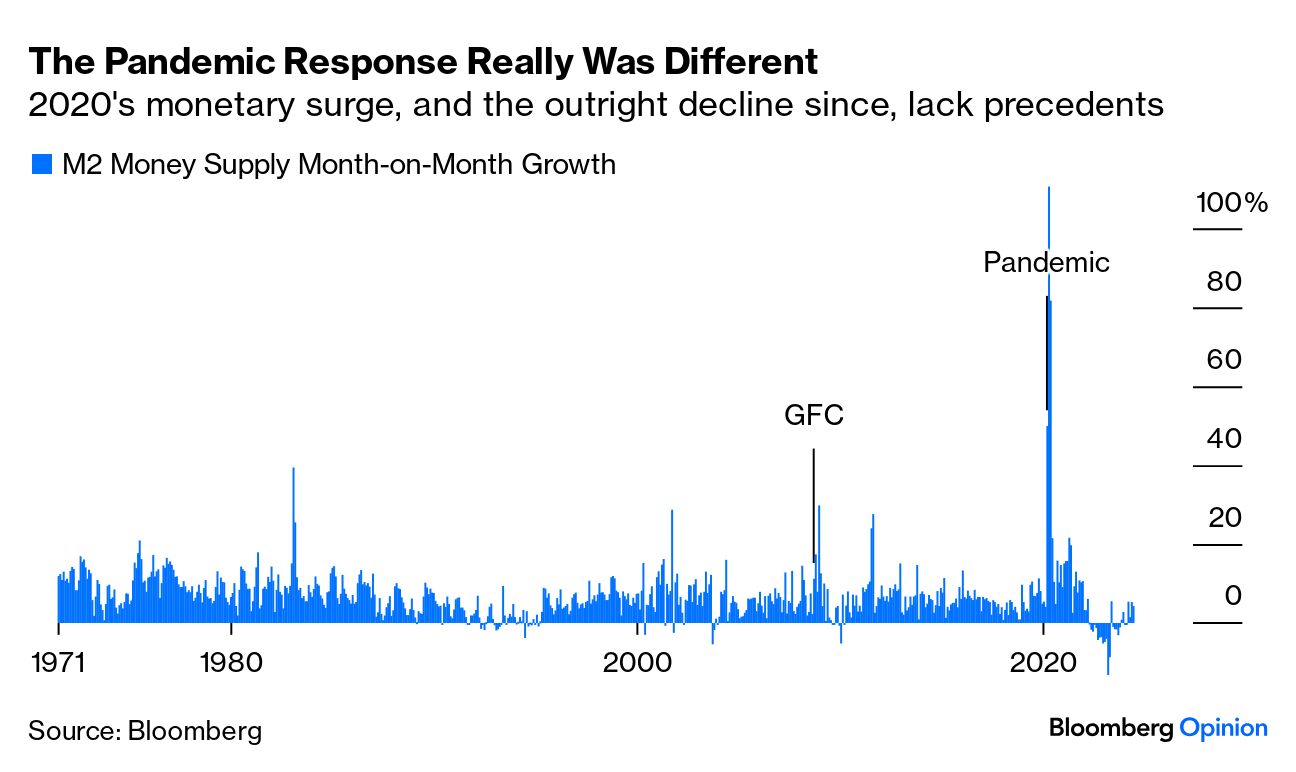

Bloomberg has a great visual on how much money supply spiked during the pandemic:

As I’ve pointed out before, this money did not go into the real economy for a while. It first went into investments, creating a level of giddiness that fueled a pandemic-stock bubble. And that drove plenty of “sideline” money into equity markets in particular: Capital inflows into US equity markets in peak-bubble 2021 exceeded the previous 19 years of inflows combined.

Anyone who thinks economics is a rational science please raise your hand.

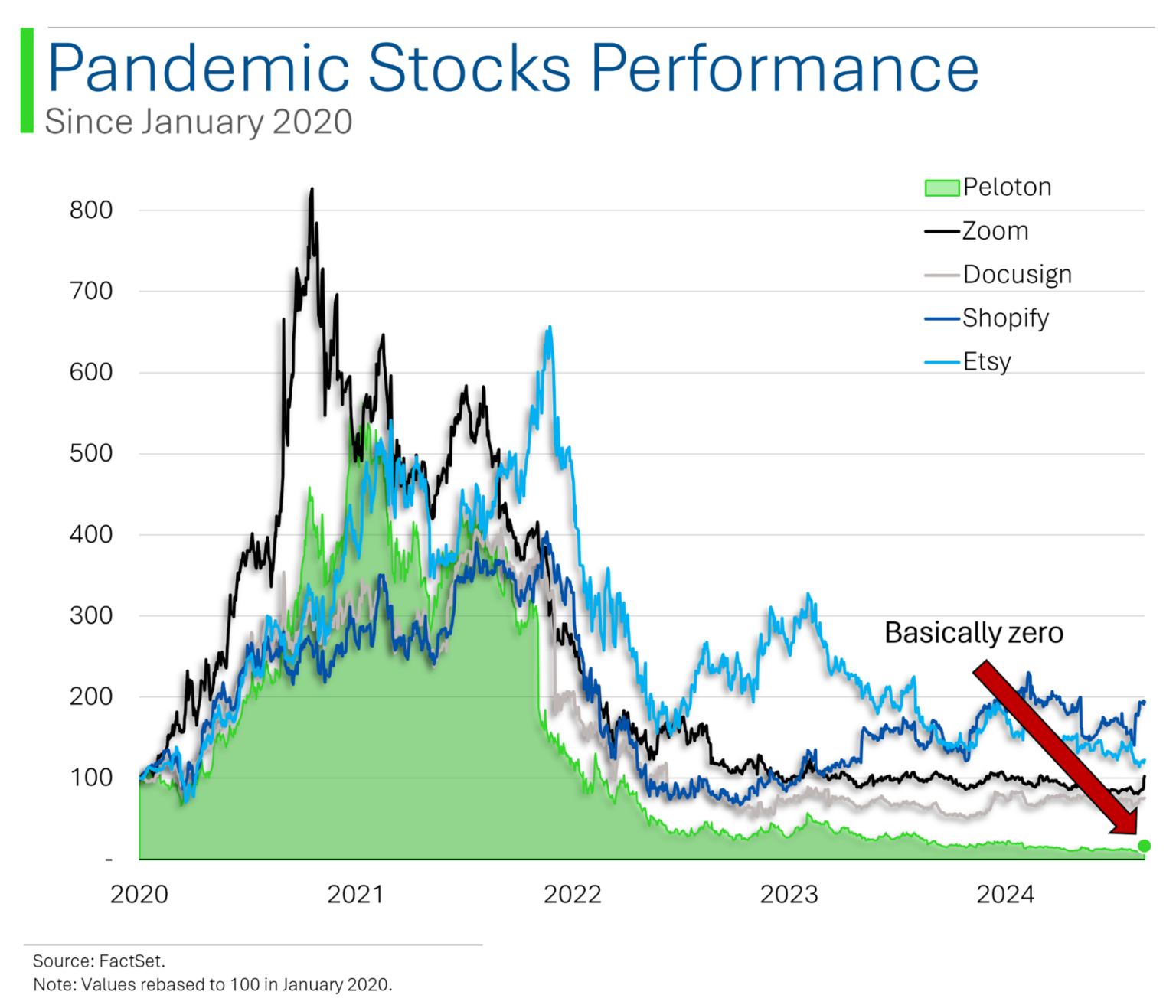

Everyone loves a winning sports team, and everyone loves buying stocks when stocks are going up. New investors flooded equity markets, driving up meme stocks and “pandemic” stocks – stocks that offered an actual thesis, unlike meme stocks, but one closely tethered to the pandemic – alike.

Easy come, easy go, as a graphic from Ryan of Street Smarts/MarketLab shows:

One obvious lesson is that investments that rise up for no good reason essentially always come down.

Watch out for this sneaky corporate finance trick

A second related to corporate finance: Ironically, the “dumber” it is for investors to buy your stock during a bubble, the smarter it is for you (if you’re a company) to issue stock during a bubble. We saw Hertz, GameStop, AMC, and several others do this. Whether this is predatory or not is your call.

Flip this logic for share repurchases – when companies buy back their own stock. When a company believes its stock is underpriced is the best time to repurchase, and vice versa.

Despite this, companies writ large do not actually have a good track record of repurchasing stock at low valuations. This is because they have conflicting motivations (and sometimes just poor judgment): Companies that issue stock options and restricted stock need to “create” new shares when those perks get exercised or vest. All else equal, new shares split the pizza into more slices without increasing the size of the pizza (as happens when companies sell new shares for their fair value in cash on the open market, a move that’s valuation-neutral).

Companies know that most investors just watch the number of pizza slices and not the size of the pizza – even some Wall Street analysts mistakenly think “more share” automatically means “dilution” – so they shell out cash (which reduces the size of the pizza by depleting company assets) to repurchase shares not when shares are cheapest but when they have the most cash. That’s often right after good performance, when valuations are highest – the worst time to actually repurchase shares.

When company managers do have a good track record – actually a wonderful track record – is when they’re investing as individuals. Academic evidence has shown that insiders can outperform the market by as much as 11 percentage points per year. (If you’re interested in monitoring insider transactions, check out BBAE’s InsiderEdge.)

Berkshire Hathaway Hits $1 Trillion

I just did an interview about Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: $BRKB) crossing the $1 trillion market cap threshold. It’s hovering just below that as I type, but in any case, it’s a trillion-ish company now.

What I flagged was that in some ways, Berkshire reached $1 trillion in spite of being Berkshire, and not because of it. What I mean is that Berkshire’s P/E multiple is 14, and the S&P 500’s is roughly 28.

If Berkshire traded at the valuation of just the average American stock (at least the average mid-to-larger American stock), it would be a $2 trillion stock instead of a $1 trillion stock.

And truthfully, in terms of quality-ness of the company, Berkshire Hathaway is far above the average American stock.

Where it may fall behind, at least in the market’s eyes, is in future growth, though I’m not sure how much water this argument holds because Berkshire has done a pretty good job of outperforming the S&P 500. I may be a biased Berkshire shareholder but I think Berkshire deserves a higher multiple.

Of course, the other side of the coin is that Apple is Berkshire’s largest holding, and Apple, like other gigantic tech stocks, has done well. Apple’s P/E is just shy of 30, though, so it’s pretty close to the market average (at least “average” in a cap-weighted sense). But overall, Berkshire becoming the eighth-largest US company by market cap with not much tech outside of Apple is like someone coming in sixth in the Tour de France on a mountain bike.

What does Warren Buffett – whose birthday is this week – think? I don’t think he cares about Berkshire’s market cap. And in a way, Buffett’s staying disciplined and not caring about market mood or what anyone else thinks is very much why Berkshire has a trillion-dollar market cap now.

Interestingly, Buffett has held off on Berkshire repurchases.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. At the time of publishing, James owned shares of Berkshire Hathaway. BBAE had no position in any investment mentioned.