Weekly Roundup: Small Caps to Rise 22%? And Do Cash Flows Justify High PEs?

Will small caps beat large caps by 22.2% next year?

One feature of the rally in US stocks we’ve had over the past few years has been the domination of large caps. I mentioned a few months ago that just 24% of stocks in the S&P 500 outperformed the index average, which is a new low.

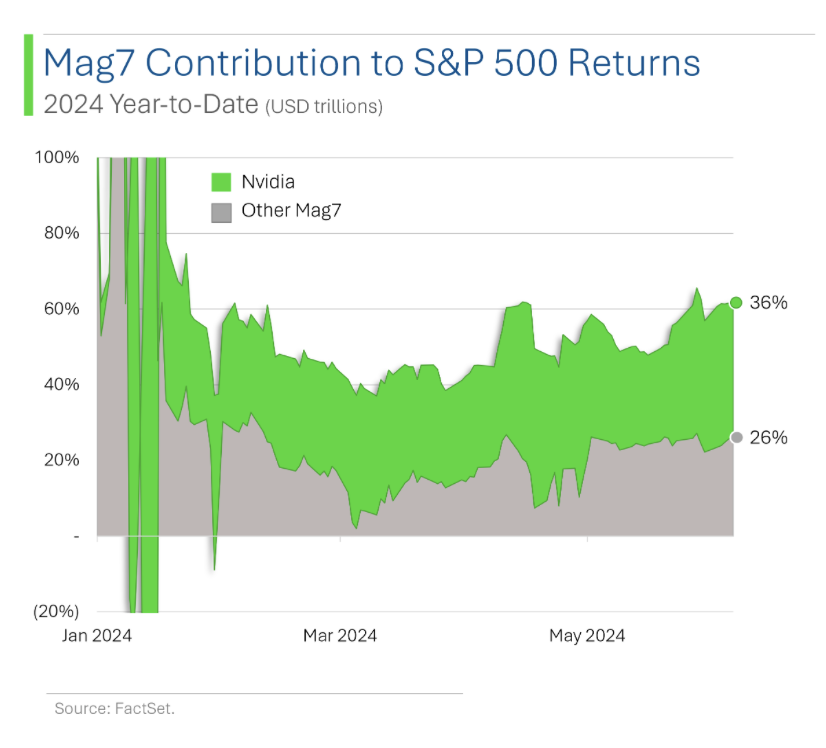

We know about the Magnificent Seven disproportionately driving the market (though not all are magnificent this year), and we know that Nvidia, most magnificent of all, is disproportionately driving the drivers, as the graphic from StreetSmarts shows:

The fact that someone is out in front tends to mean that someone is getting left behind. In one sense, that’s the 76% of S&P 500 stocks that underperformed the index, most of which are midcaps.

But small caps are even more left behind.

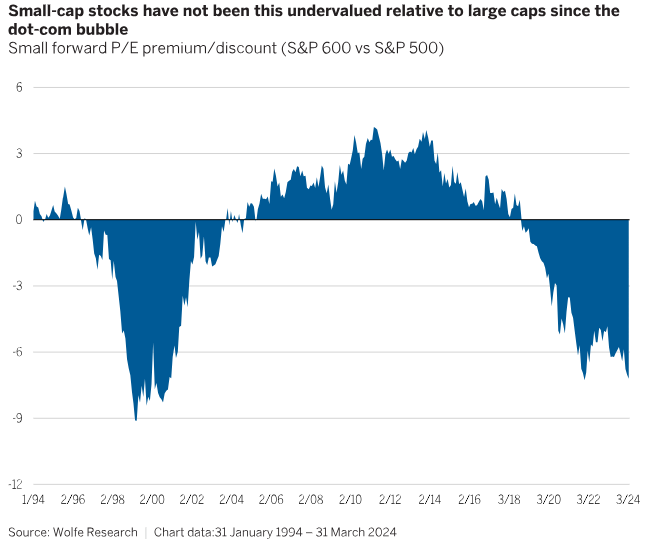

My friend Whitney Tilson shared some small-cap charts in one of his daily emails recently. One shows relative valuations of small caps and “large” caps (again, though the S&P 500 is commonly thought of as a large cap index for holding roughly the 500 largest public companies in the US, there actually aren’t 500 large caps in the US, so the index is more mid-cap focused by number, and has historically held some small caps, too).

I might dispute the word “undervalued” – it’s probably true, but “cheaply valued” would have been indisputably correct – but the point is obvious: there’s a huge spread.

Now a spread doesn’t mean that the lower-valuation “thing” is cheap – it might be fairly priced, and the higher-valuation thing is just really rich. And vice versa. Maybe they’re both irrationally priced, in opposite directions, or maybe just one is. This is why I try to avoid moral judgment-type words like “undervalued” based solely on spreads.

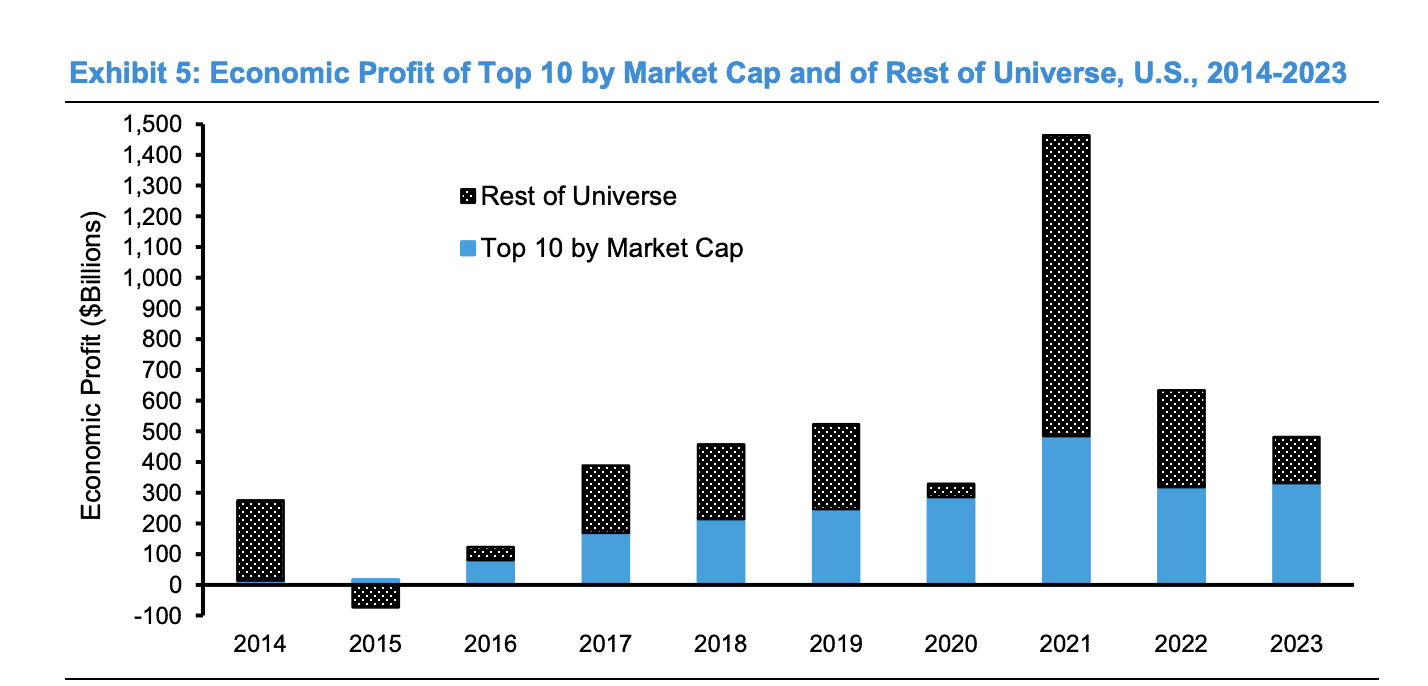

Just to belabor this slightly, take a look at economic profit generated in 2023 by the largest 10 companies by market cap, per Bloomberg (pardon my slightly sloppy screen grab). The biggest stocks may have risen notably, but they were bringing home more bacon than all the others combined.

All this said, this is the second-longest period of small-cap underperformance. Per an Institutional Investor article earlier this year, prolonged small cap underperformance is usually followed by outperformance:

“Jefferies analyzed seven similar periods of significant underperformance of small vs. large stocks. On average, after these difficult periods, small caps outperformed large caps by 22.2 percent, 10.5 percent, and 9.8 percent annually over the subsequent 1, 3, and 5-year periods, respectively.”

I’m not against this thinking, but I’ve never been a huge fan of exclusively using “do this because it’s generally worked a certain way in the past”-type thinking. Repeating patterns may be repeating for reasons. But they may also be artifacts, more random than we think, or just less applicable in different times.

How well has that “inverted yield curve has been 100% accurate in predicting recessions” advice been working out?

(If you’re new, when short-term government bond rates (typically proxied by 2-year rates, but not exclusively) go higher than long-term government bond rates (typically, 10-year rates, but again, people mix and match), it’s weird and considered a bad omen that’s basically always preceded recessions. Except it hasn’t in the past few years, despite some long inversions.)

Small caps have more debt than large caps, and more variable rate debt. This meant rising rates were bad for them. As rates fall, that variable alone will be good for them.

But if the US finally does have the recession that’s been predicted for years, small caps would presumably suffer more, because small caps tend to have more domestically focused operations.

Small caps have tended to lead the market out of recessions, outperforming large caps as things finally turn around.

But we are not in a recession. We are not even in a period of falling interest rates, despite earlier predictions we would be by now.

I won’t make a prediction, though I’d sooner bet on small caps at current prices than against them. But we’ve got a lot of government spending that’s distorting things, and had super low rates for a while (which distorted things).

Famous investor John Templeton said that the four most dangerous words in investing are: “This time is different.” He’s wiser than I am and his quote is correct overall. But I think it’s safe to say that sometimes, things are different in investing.

If we avoid a recession, my guess is that small caps do well over the next five years. If a recession hits, they may be closer to being fairly priced.

Are US Stocks Actually Not Expensive?

If you’ve been reading these BBAE Roundups for a bit, you know that one topic that comes up semi-frequently in various forms is whether or not stocks are expensive.

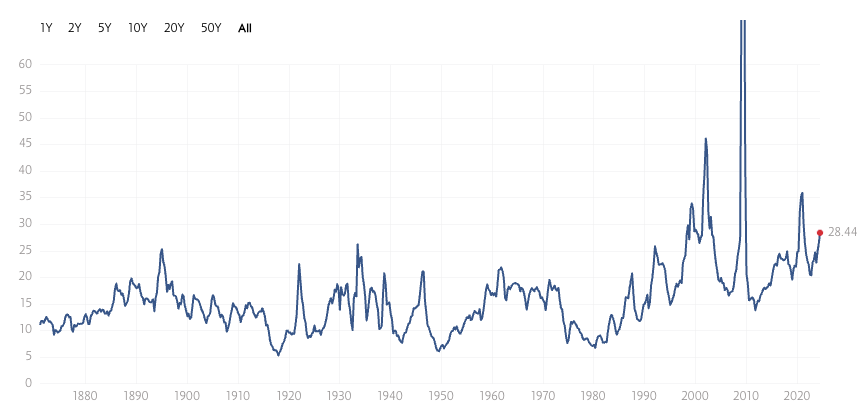

It is, in a sense, one of the most important questions in investing. And as I’ve shown before, on a historical PE ratio basis, US stocks are definitely expensive, in the sense that the current 28 PE is higher than the average of 16 and the mean of 15.

If we were to invest just based on this chart, we’d flee the market.

If you’d waited for below-average PEs, you’d have missed a generation of investing

In fact, if we were willing to invest at average PE levels, we’d have only plunked money down in 2011 or so, a bit after the Global Financial Crisis. We’d have missed adding any further money since then.

And if we’d had a higher standard – if we’d refused to invest unless the market was below its average PE ratio, which sounds very reasonable in the sense of seeking to buy at below-average prices – we wouldn’t have had any whole-of-market buying opportunities since the 1980s, at least based on eyeballing the chart.

Of course, individual stocks may ebb and flow, but if your strategy was to buy an S&P 500 or whole-market ETF when the market dipped below its average PE ratio, the last time you got a real window to do that was 35 years ago. Incidentally, that was before ETFs were created.

So you either have to accept that this time is different to some degree, or you can’t invest at all.

Sam Ro, who writes Tker.co, has made the case that the market has structurally changed. That companies are less indebted than before, that workers are more productive than before, and that the S&P 500 has shifted toward asset-light companies that are more financially efficient than heavy industry companies of yore.

A new reason to not fear “high” valuations

Companies are better now, to paraphrase Sam, and thus it’s OK to pay more for better companies.

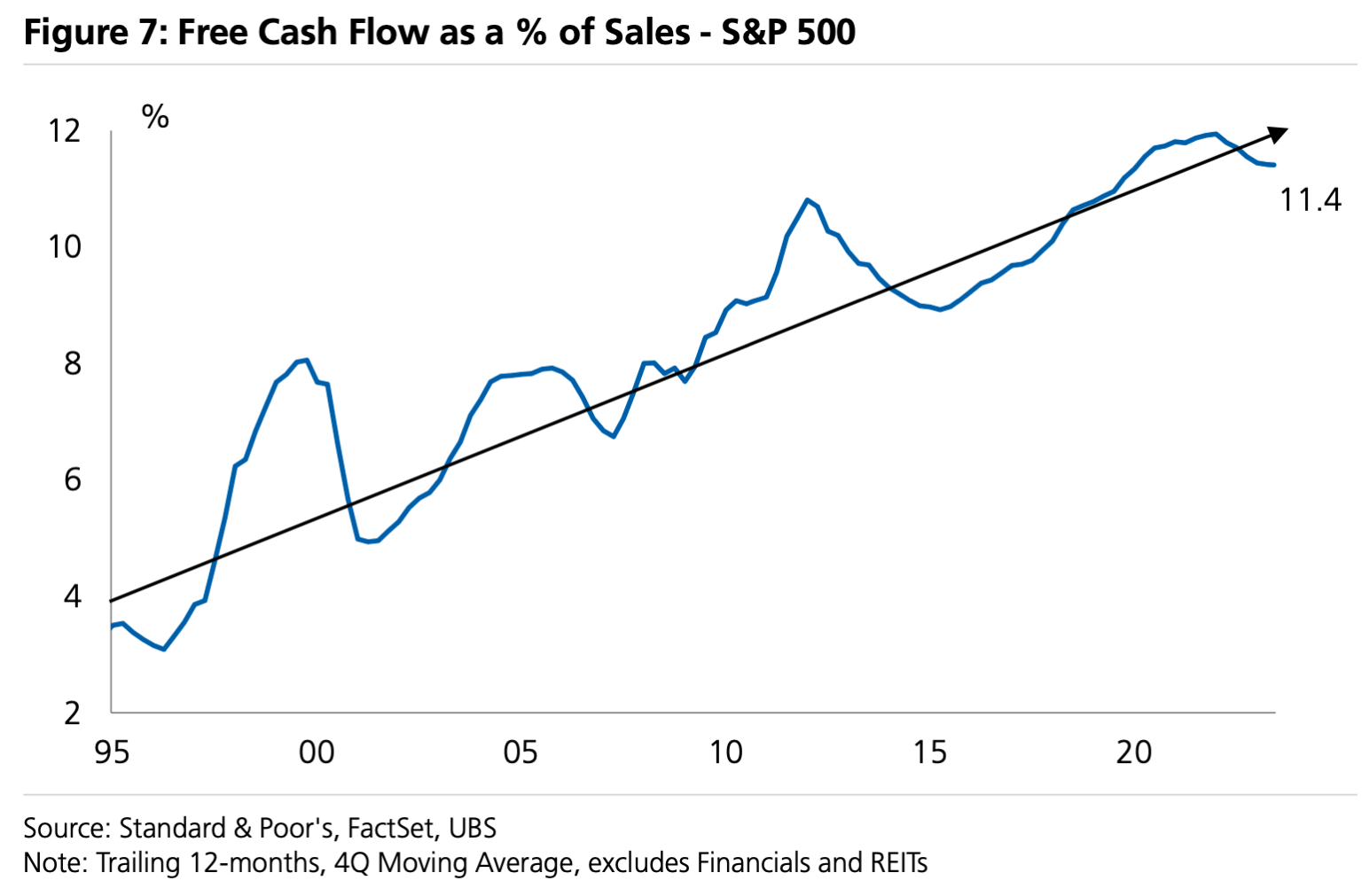

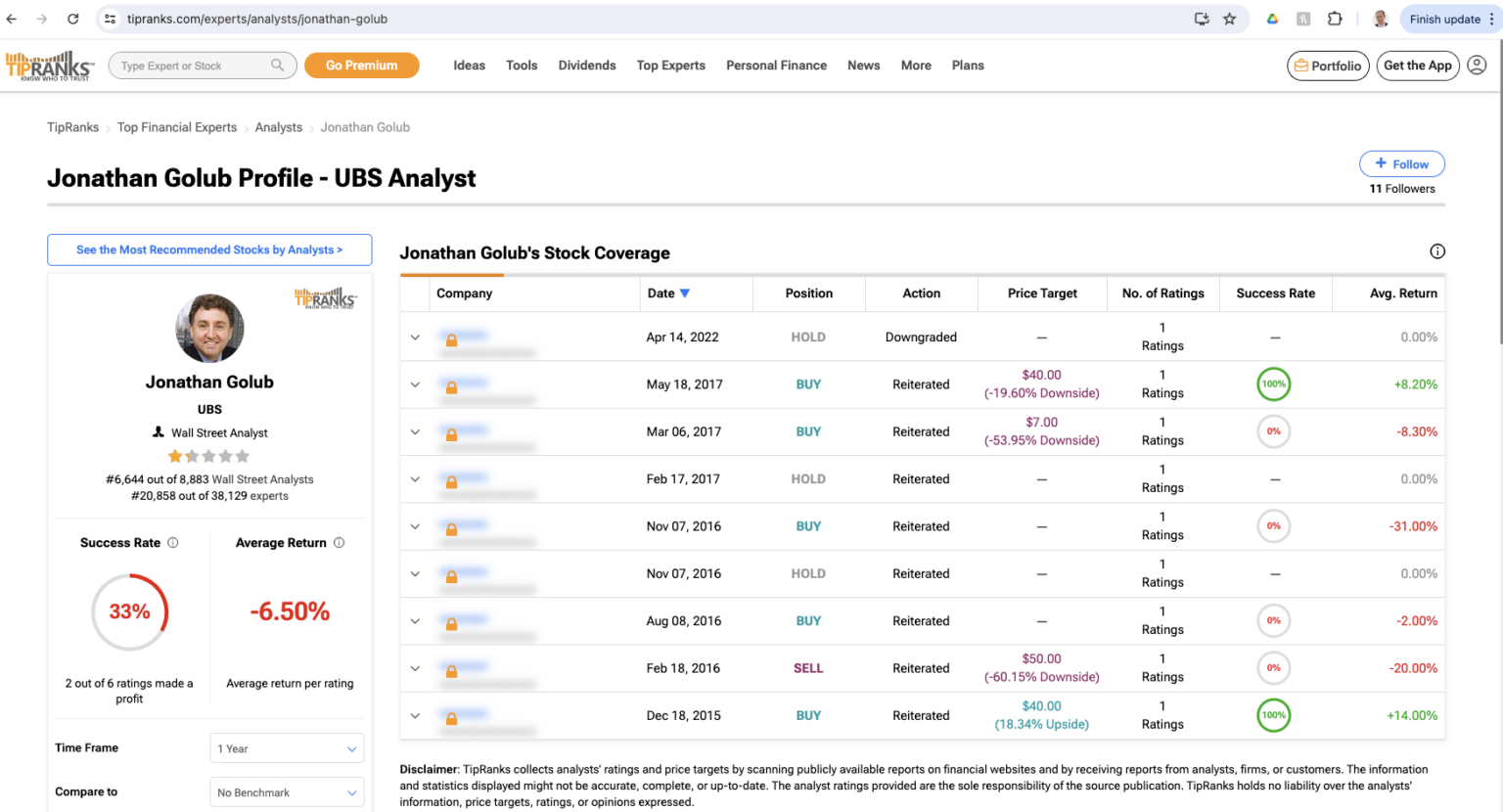

Sam also showed a chart from UBS analyst Jonathan Golub, showing how free cash flow as a portion of sales – free cash flow “profitability” – has been trending higher and higher over the past 30 years.

Free cash flow is basically a purer version of earnings, or at least its proponents would describe it as such. Accruals and other non-cash accounting adjustments are factored out, meaning cash is the only thing that’s measured.

Anyway, it looks good – both for supporting the case that current market valuations that seem high when compared to prior market valuations are actually not so high when compared to nitty-gritty reasons stocks should have higher prices. Like higher earnings or cash flows.

I’m not saying the market is cheap now, but if you’ve been holding off investing based on comparing current PE ratios to historical ones, I can say that such a perspective is missing too much relevant information to be useful.

If there’s one principle underlying everything I’ve said today, it’s to not let a single data point drive your decisions.

Jonathan Golub would likely agree.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.