Weekly Roundup: S&P 500 Valuation, T + 1

Is the S&P 500 cheap or not?

Investors like to wonder whether the stock market is expensive or cheap.

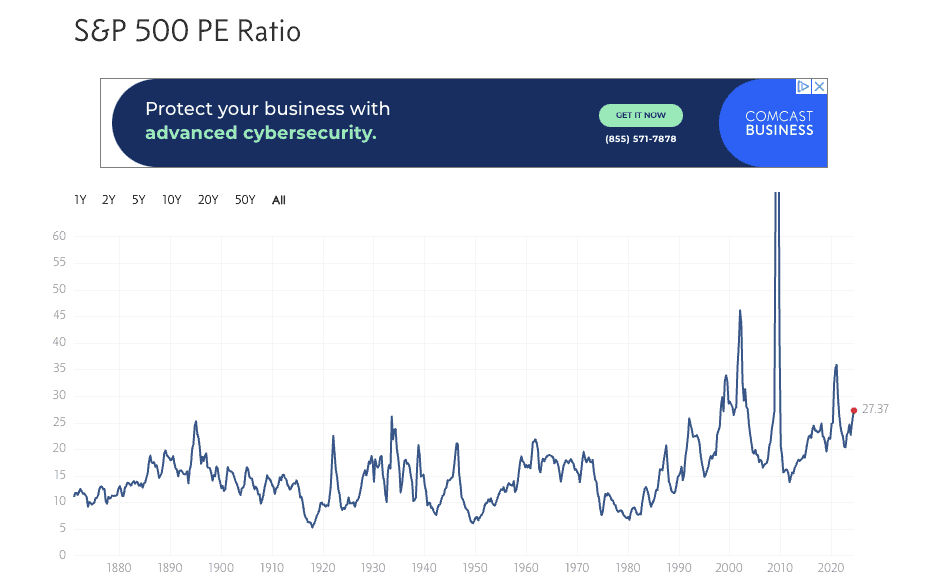

One way to “price” the market is with its aggregate price-to-earnings (PE) ratio. PE is not perfect: It’s generally rearward-looking, whereas in principle, investors are buying the future earnings of a company. From this lens, PE is illogical. PE tends to rely on a single year’s earnings, which can be skewed by cyclicality, accounting issues, one-time events, and whatever else.

But PE is really, really easy to use. So it’s by far the most commonly used valuation metric.

According to Multipl.com (whose graphics I used below), the S&P 500’s median PE ratio is 15, and its mean is 16. Some sources say it’s higher – around 17 – but either way, the current PE of 27 is higher than average, and thus scary to some:

And if you’re seeing that too-large-for-the-screen spike in 2009 and wondering why stocks were so pricey, they weren’t: Stock prices dropped in 2009, during the Global Financial Crisis, but the market was actually prescient. Earnings dropped even more than price, in fact, but the market wisely saw the earnings drop as temporary and didn’t punish stock prices too much – reasoning (correctly) that earnings would pick back up. In other words, 2009’s high PEs were a denominator issue versus a number one.

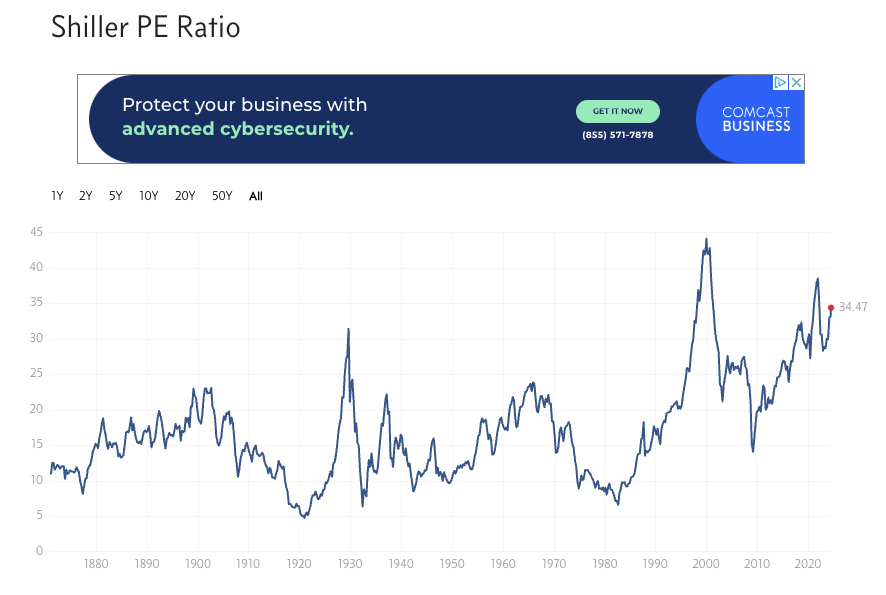

But if you’re into being scared, have a look at the Yale economist Robert Shiller’s PE ratio, which averages and inflation-adjusts the last 10 years of earnings. Also called the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio, the Shiller PE ratio is heralded as a better predictor of stock prices than its simpler brother.

And, of course, the current Shiller PE is high, at 34. Also according to Multipl.com, its median is 15.98 and average is 17.12.

It probably doesn’t help that a guy called stocknoob4111 thinks the Shiller PE “seems mostly useless” (the poster’s name doesn’t inspire confidence, but he started an informative thread, especially if you’re new to the nuances of PE analysis).

Reasons the stock market may not be as expensive as it seems

It’s hard to argue that the US stock market is cheap, but a few perspectives are circulating that may, fairly, argue that this time is a little different:

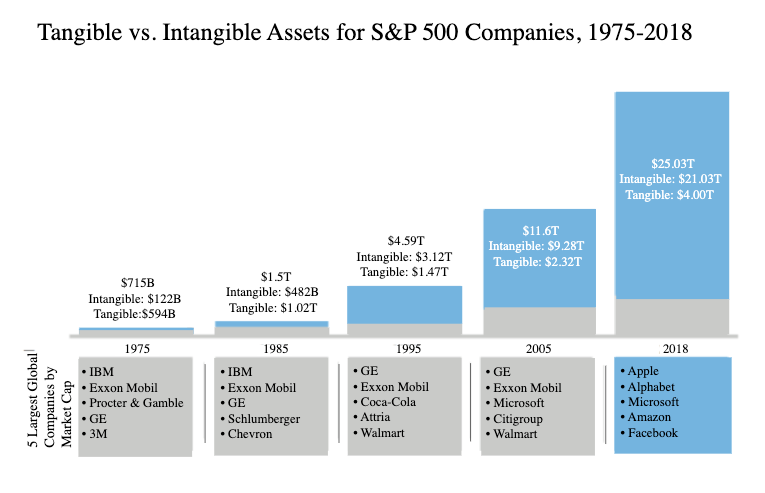

- US companies have more intangible assets than they used to. Factories and hard assets are no longer the mainstay. A graphic from the UCLA Anderson Review shows this clearly:

- The US economy is less labor-intensive than it used to be. In fact, the tide has shifted so quickly that America has a shortage of labor. This point goes together with the prior one; we’ve mostly transitioned from a “things” economy to an “ideas” economy.

- AI will exacerbate this trend further. With AI handling a lot of white-collar grunt work, “adding value” in business will increasingly come from making good decisions, rather than number of widgets stamped or time at the office.

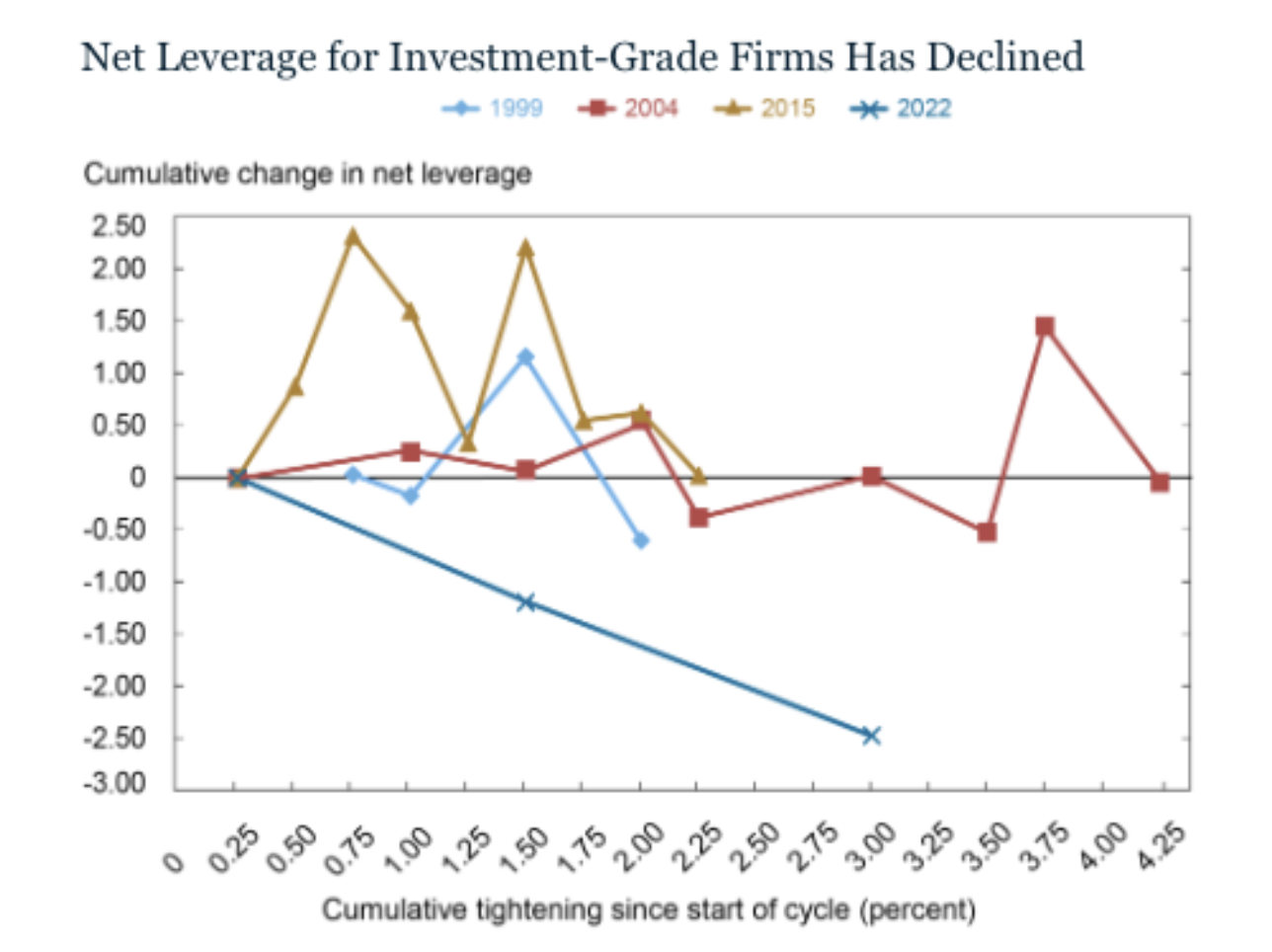

- US corporations are less levered now, and tend to have lower-cost debt. The graphic below is from the New York Federal Reserve’s blog and basically shows how quickly and linearly leverage dropped with this current Fed tightening cycle relative to prior cycles. Like the US household, the US corporation is relatively healthy, financially speaking.

Again, I’m not saying the market is cheap. I am saying that there’s an argument that the economy evolves in ways that add more value to humankind over time – just look at the value that surrounds us now compared to 100 or 200 years ago – and so it’s not surprising to see that extra value reflected in stock prices, meaning that average PEs could be reasonably expected to tick up slightly over time.

OK. But have we gone past “slightly?” Nobody knows, but possibly.

T + 1 settlement, GameStop, and non-dollar investors

I have a hot dog and want $5.

You have $5 and want a hot dog.

Our transaction is simple.

Now pretend it’s the 1920s, and pretend I have a paper share certificate whose market price is approximately $100.

You have $100 and want my share.

Our transaction is still pretty simple.

The US has just returned to “transaction date + 1” – or “T + 1” to be short – trade settlement, which it had in the 1920s, as horse couriers needed a day to haul share certificates around.

What’s the deal with T + 1?

From the 1920s to the early 1970s – roughly the time it took the US stock market to regain its 1929 peak – paper certificates were physically moved around. In 1973, the Depository Trust Company was created with the idea of immobilizing them: Rather than being carted around, paper certificates were kept on file with the DTCC and book entries handled ownership changes.

But – and this is the tricky part for most people – unlike with hot dogs and cash, the counterparties in a stock transaction often don’t have the cash or stock at the time they agree to a trade price. They might. But as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine points out (registration may or may not be required, depending on how many Bloomberg articles you’ve read lately), the buyer may need to get a margin loan or convert currency to have the cash ready, and the seller may need to call back shares loaned out to a short seller.

These actions take time, albeit less and less as technology improves; in 1973, settlement happened five days after a trade was agreed to. By 1993, the SEC moved to T + 3, and then T + 2 in 2017.

But, importantly, it’s not just a tech issue – if we can have ATMs in Antarctica, we can process trades quickly if everything is “there” – it just takes time to get everything there. If there’s not enough time, there will be a “settlement fail” (link is focused on European markets but similar principles apply in the US).

T + 2 seemed fine until the meme stock frenzy. One requirement is that the broker must post collateral at the DTCC just in case something happens with either side before the trade clears, and during the surge in meme stock trading, Robinhood famously didn’t have enough collateral with the DTCC, which caused them to restrict meme stock trades, which angered meme stock traders and even prompted an appearance before Congress.

Sidestepping the question of whether or to what extent Robinhood was at fault, Gary Gensler and the SEC see a shorter settlement time as a win in that a shorter time window means less time for things to go wrong. The industry has pushed back, generally saying that a shorter time window means less time to fix things that go wrong.

Either way, T + 1 is here. If you’re a regular investor, it’s not likely to change your life much. You’ll get cash quicker if you sell. It’s going to be hardest on non-US traders, who, unless they’ve got US dollars already at hand, often need to turn to the foreign exchange markets to convert local currencies into US dollars to make the trade.

The problem? Foreign exchange spot trades typically take two days to settle.

The solution? Move to the US – or move to T + 1 everywhere

Also from Bloomberg:

“More than half of European firms with fewer than 10,000 staff are planning to either move people to North America or hire overnight staff in Europe or Asia, according to a survey sponsored by the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation. …

In its letter to the SEC, Baillie Gifford said US FX desks typically close early on Friday evenings, which might mean trades need to be made in Asian hours on a T+0 basis. It suggested US regulators encourage banks to extend their trading activities to at least 6 p.m., five days a week.”

Aside from foreign trading firms, ADRs and ETFs that own ADSes (banks sometimes buy foreign stocks and create a block of equivalent US-trading shares called an American Depositary Receipt (ADR); individual shares of ADRs are called American Depositary Shares) will seem to have issues if they own underlying foreign stocks that have settlement times longer than T + 1.

Canada and Mexico also moved to T + 1 in sync with the US, and it’s hard to imagine US equity markets – the largest in the world – moving to T + 1 without the rest of the world following suit sooner or later, and probably sooner.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.