Weekly Roundup: Trump Up, Geopolitics (and Semiconductors) Down, Fed’s Next Rate Cut

Trump Talk & Biden Tariffs Spook Tech Investors; Nvidia and ASML Down

I’ll talk shortly about the resilience of the US market after the Trump assassination attempt (assassination attempts have, historically, been negatives for markets, versus driving them to all-time highs), but since then, the tech sector had a mini-shakeout. Wednesday (July 17) was the Nasdaq’s worst day since 2022.

It seems to have happened for two reasons:

- A month-old Bloomberg interview with former President Donald Trump finally got published, in which Trump seemed surprisingly unsupportive of Taiwan, which he thinks “took about 100%” of America’s chip business (and which has 92% of the world’s most advanced chipmaking capacity).

- President Joe Biden discussed invoking stricter trade rules to prevent China from importing chipmaking technology via third-party countries

- (Bonus or potential reason) In that Bloomberg interview, Trump also hammered home the idea of pursuing a weaker dollar. However, Trump’s policies (tax cuts, tariffs, bringing manufacturing “home”) aren’t typically things that create weaker currencies – the opposite, in fact, and the market has been betting on a stronger US dollar with Trump likely returning to office. So it’s possible that the market interprets Trump’s interview comments as meaning more uncertainty is coming, or simply that Trump is confused.

Trump: No friend of Taiwan, apparently

Anyway, Bloomberg published an interview it did a month ago (subscription may be required) with the former president, in which Trump made the following comment on Taiwan:

“Taiwan should pay us for defense. You know, we’re no different than an insurance company. Taiwan doesn’t give us anything. They took all of our chip business. They’re immensely wealthy. And I don’t think we’re any different from an insurance policy. Why? Why are we doing this?”

Trump’s antagonism surprised investors, and is in marked contrast to President Biden’s position; Biden has repeatedly either intimated or outright said in a slip-of-the-tongue way (which some felt was accidental, and others deliberately “accidental”) that the US would defend Taiwan if China were to invade.

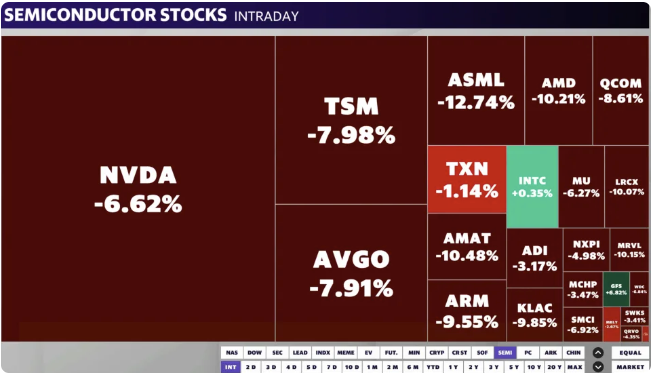

A potentially new status quo means the markets will adjust, and adjust they did, slamming Nvidia (Nasdaq: $NVDA) down more than 6%, and Taiwan Semiconductor (Nasdaq: $TSMC) down 8% in a day.

Biden: New export restrictions in the cards

Furthering this tech drama were reports that the Biden administration is considering additional export restrictions on semiconductor-related sales to China through something called a Foreign Direct Product Rule. This legal avenue, introduced in 1959, is fairly technical (exact rule via this link) but intends to address situations wherein the US is restricting certain exports to a certain country (or industry, set of companies, etc., in a country), but suppliers from another country – generally using some material amount of US exports (although “material” is debated) – continue to export products that the US doesn’t want the sanctioned country to have.

For a goofy but true-to-form example, pretend Bob doesn’t want to sell a mobile home to Fred. But Bob’s friend Steve buys some mobile home parts from Bob, as well as some wood from Lowe’s, along with parts from other suppliers, and then goes to help Fred build his mobile home. Bob may feel semi-betrayed, and that if Steve’s a true friend and really cares about Bob’s interests, he wouldn’t enable Fred to end up with a mobile home. Thus, if Steve doesn’t stop, Bob may have to stop selling to Steve, too.

In this case, the “Steves” are Dutch ASML (Nasdaq: $ASML) and Japan’s Tokyo Electron, both of which enable China’s semiconductor industry using US technology. The FDPR is used from time to time (such as on Huawei a few years ago) when the US really wants to restrict something.

Not everyone agrees that sanctions work: a widely held view among economists is that technology sanctions tend to be less effective than intended because they’re so easy to work around in today’s interconnected economy. But either way, the FDPR is the trade equivalent of bringing out the big guns; it means getting tough on third-party countries and companies, which can get awkward.

This all made Wednesday a bad day for semis – the semiconductor sector reportedly lost more than $500 billion (per Morning Brew newsletter); the Yahoo! Finance graphic below shows the carnage:

DJIA: New high, though

The Dow Jones Industrial average, ironically, reached a new high on Wednesday, so it wasn’t bad news for everyone.

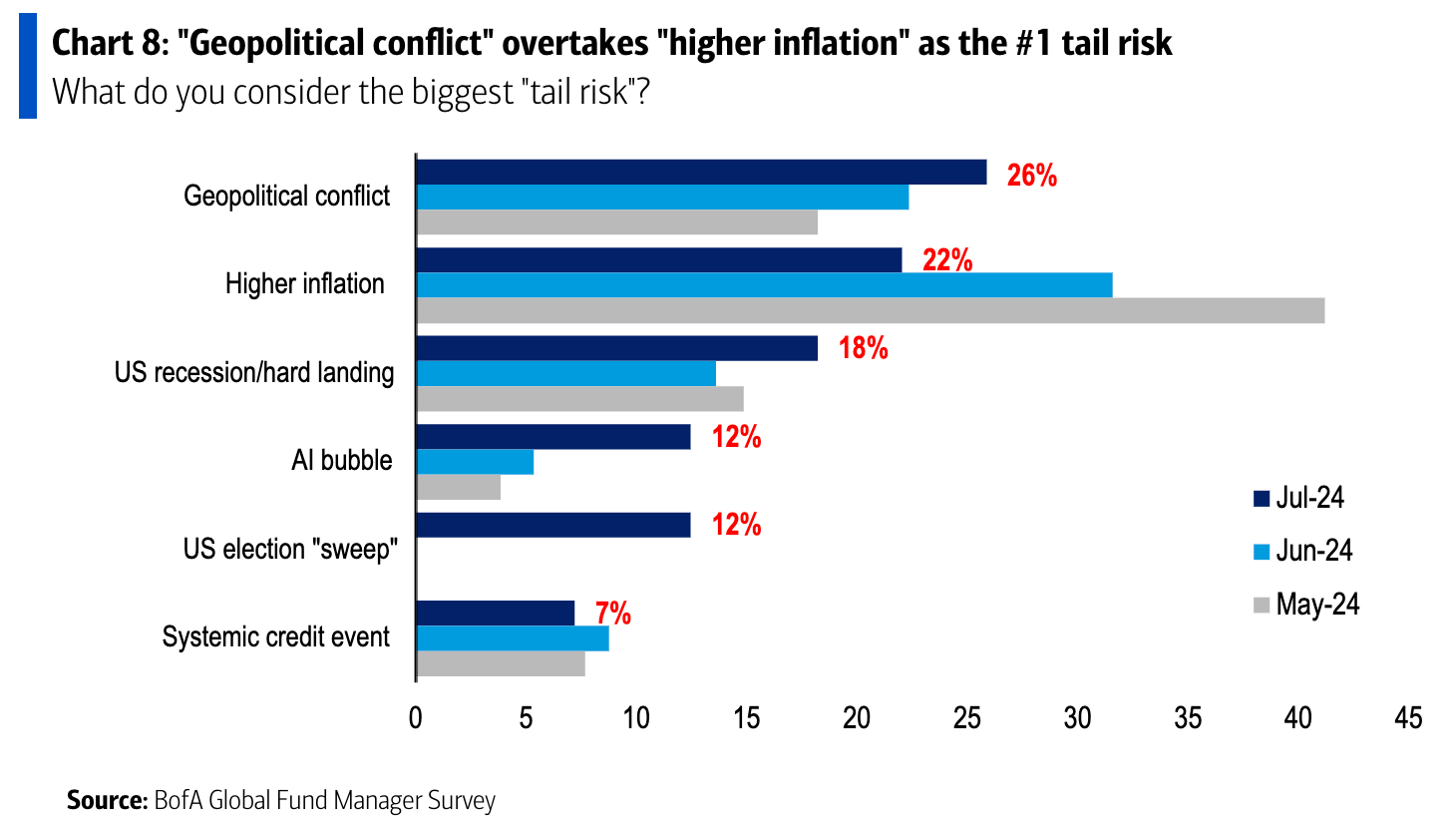

But beyond chips – which now occupy a surprisingly large portion of US market cap – this week’s news validates investors’ growing geopolitical worries. Per a Bank of America graphic shared by Sam Ro (of Tker.co), with inflation cooling, geopolitics are fund managers’ greatest worry:

But so what? I mean, what can or should we do as investors about political risk?

To me, the key word is balance. Politics and geopolitics affect portfolios. But because politics can depend on the decisions of literally one or a few people, I see political risks as some of the most difficult risks to anticipate or do anything about.

The key to predicting politics: Knowing that we can predict less than we think

“Politics” is a big word: Certain US states may be seeing trends in utility ratemaking cases over time – a quasi-political thing – and I’d certainly take that kind of political information into account when evaluating utility stocks in that state. But really big-picture things can be part of highly interconnected cause-and-effect chains.

Plus, life is just full of surprises. If you’d bailed on the semiconductor industry years ago on the grounds that the West was starting to cut Chinese imports off, thus denting demand – a thesis that made reasonable sense at the time – you’d have missed the benefit of AI swooping in and driving the iShares Semiconductor ETF (Nasdaq: $SOXX) up nearly fivefold from its 2020 lows.

Beware overreaction to politics, in other words.

Trump shooting and the stock market

I’m of the belief that an assassination attempt, regardless of outcome, is fundamentally a tragic thing that transcends political partisanship.

From a market lens, the market’s reaction to the assassination attempt is a curious phenomenon that shows just how optimistic the stock market is about Donald Trump.

According to CFRA Research, the prior 10 Presidential assassination attempts have seen the market subsequently drop by 1.1% on average.

Yet on Monday, July 15th, the first market day after the shooting, both the S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average hit new highs.

For whatever reason, the stock market really likes Trump.

I’ve already covered, in a prior BBAE Blog post, some of the stocks that may win in a second Trump term, for various economic reasons.

Trump Media & Technology: the stock that’s not a stock

One stock that got a bump is Trump Media & Technology (Nasdaq: $DJT), which spiked from $31.25 to $46.00 the Monday after the shooting (the stock has since settled down in between those prices, but it’s still notably higher than before the attempted assassination).

What’s fascinating is that Trump Media, which owns Truth Social, is essentially an economic or sociological experiment: It’s a way for Trump fans to “vote” their support in the market, and a reminder that economics is a social science.

Trump Media’s market cap exceeds $7 billion, but its revenues are about the same as a single busy McDonald’s restaurant.

Truth Social’s user base is declining, too.

And economics aside, from the beginning, Trump Media and its SPAC, Digital World Acquisition Corporation (DWAC), have been involved in a steady stream of drama.

The original hullabaloo was, years ago, that DWAC, as a SPAC, wasn’t supposed to have had a deal in mind when it went public (at least one reason being that investors buying the SPAC thinking, per its SEC disclosures, that it’s truly a “blank check” company are not actually getting a blank check company) but it had already had substantive discussions with Trump Media (owners of Truth Social). “Substantive” was debated, but the deal eventually happened, with DWAC paying an $18 million penalty.

There’s more, but if you withheld the company name and only described these attributes – almost no material revenue, a declining user base, drama, and a very high valuation – to a trained investment analyst, you will get a predictable response. Analysts are hard-wired to flee from such precarious investments, if not short them.

With a few stocks, economics don’t matter

The point is that none of this matters.

The point is that economics is a social science. Historically, stock prices have reverted to means set by company economics, but the GameStop saga of 2021 and Trump Media buck the trend, because some investors invest for non-economic reasons.

I tend to think we’ll see more of this in the future stock market, meaning these companies are vanguards, versus end-destination stories.

With GameStop, most investors were probably just trying to make money from the frenzy, but the frenzy was started by folks motivated, at least in part, by the ideological idea of forming a citizen army of small investors to band together and stick it to the “enemy” hedge funds who were short the stock.

With Trump Media, I’d say it’s a mix of supporters who simply want to show support, regardless of profits, and supporters who blend support and profit motives, trusting that if they simply join the bandwagon, things will work out, as well as some financially sophisticated non-supporters who seek to profit off momentum created by the first two groups.

Fed interest rate cut coming soon

Around 2022, a certain species of economic news watcher roamed the internet: the Inflation Doomsayer.

“Real inflation is far higher,” they’d say.

“The US dollar [and/or the British pound] is doomed,” they’d say.

Central banks had, after years of attempting to conjure inflation to no avail, finally conjured it – with a vengeance. And now this Frankenstein’s monster had broken free of its chains, presumably not stopping until it kneecapped the world’s major economies.

It sounded compelling. I’m guessing it helped to sell books or newsletters, and gain social media followers.

But, thankfully, it turned out to be wrong.

Sorry, inflation doomsayers: You were just wrong

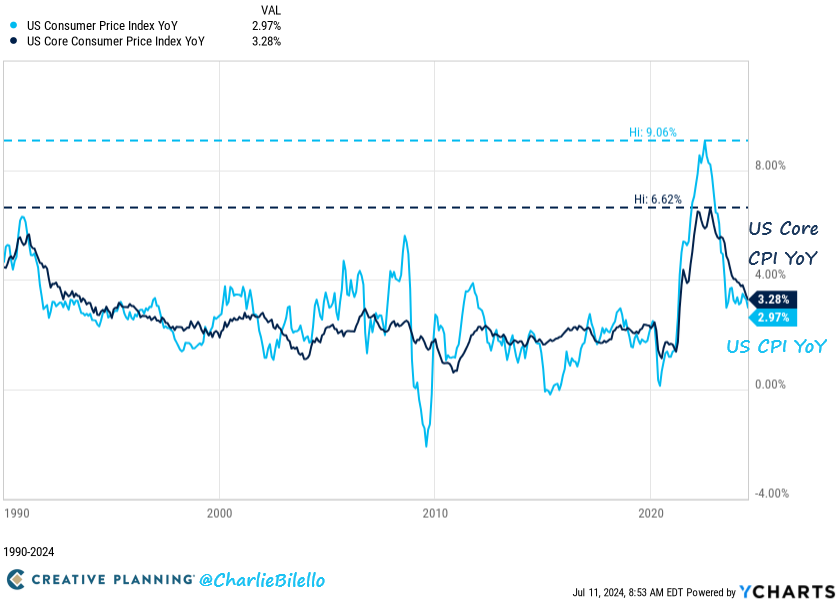

After peaking at a rightfully scary 9% in 2022, inflation has taken a nosedive, as you can see from Charlie Bilello’s chart below.

Another nail in the doomsayers’ coffin is this week’s CPI figures, which both came in slightly below market expectations: June’s headline CPI was 3.0% vs. a 3.1% expectation, and core CPI, which excludes food and energy because they’re especially volatile, was 3.3% versus 3.5% expected.

Now, the little doomsayer in me would freely admit that 3% inflation is still above 2% inflation, which is the Fed’s long-term overall target. But we’re getting closer, and the Fed itself announced a while back that it’s no longer trying to hit that number every single month; it’s more of a loose target to regress to.

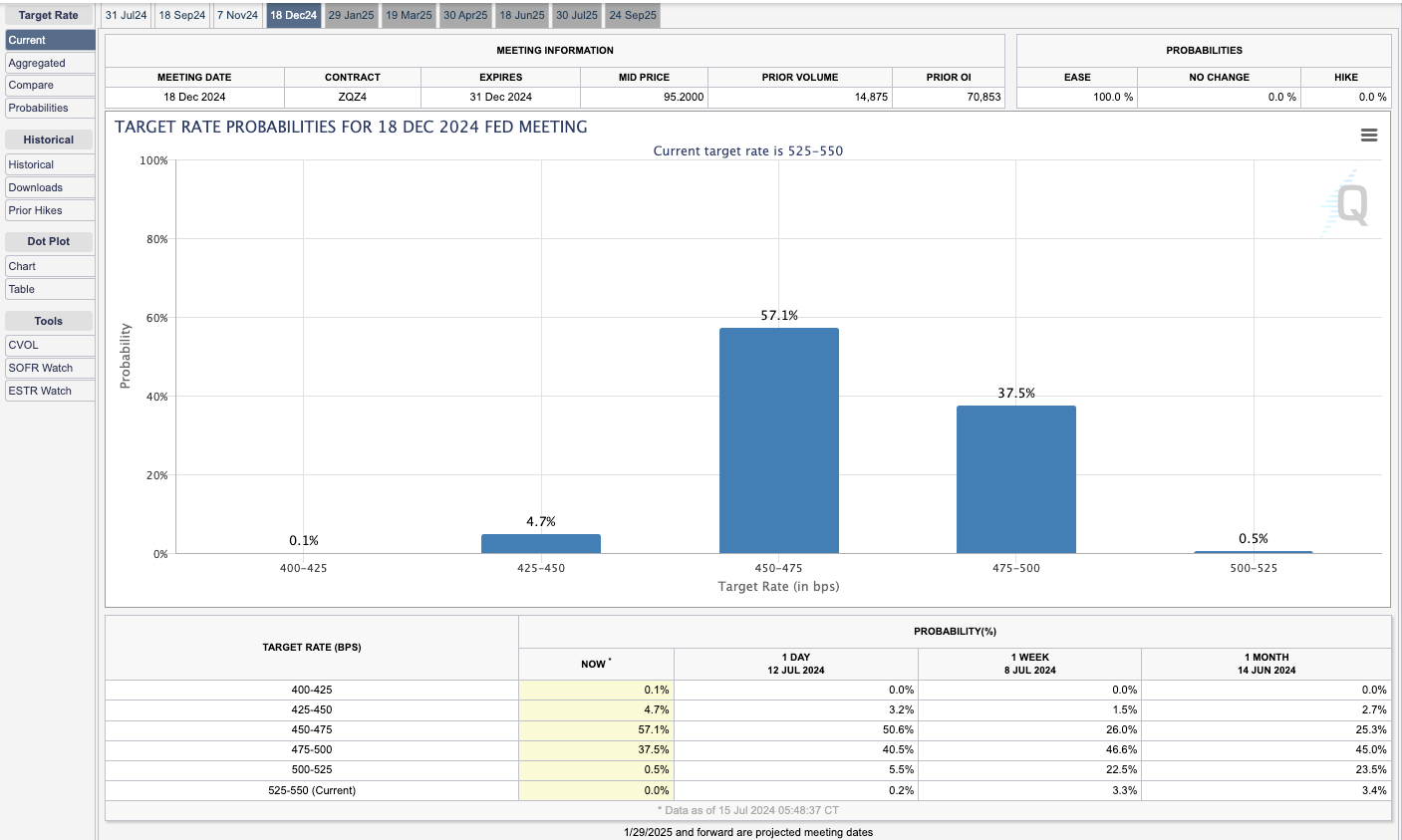

Upshot for investors: The Fed is now massively more likely to cut rates – odds favor September – according to the CME FedWatch Tool.

For comparison, the Fed’s current target Fed Funds rate is 5.25%-5.5%.

This current Fed Fund range of 5.25% to 5.5% literally has zero probability of being an outcome by December, per the tool. (NB: As I’ve written about before, the interest rate prediction market has been very, very wrong in the past.)

In case the numbers are hard to read, a month ago, the market was pricing in a 25% chance of a Fed Funds target range of 4.5%-4.75% by December. Now, it’s 57%.

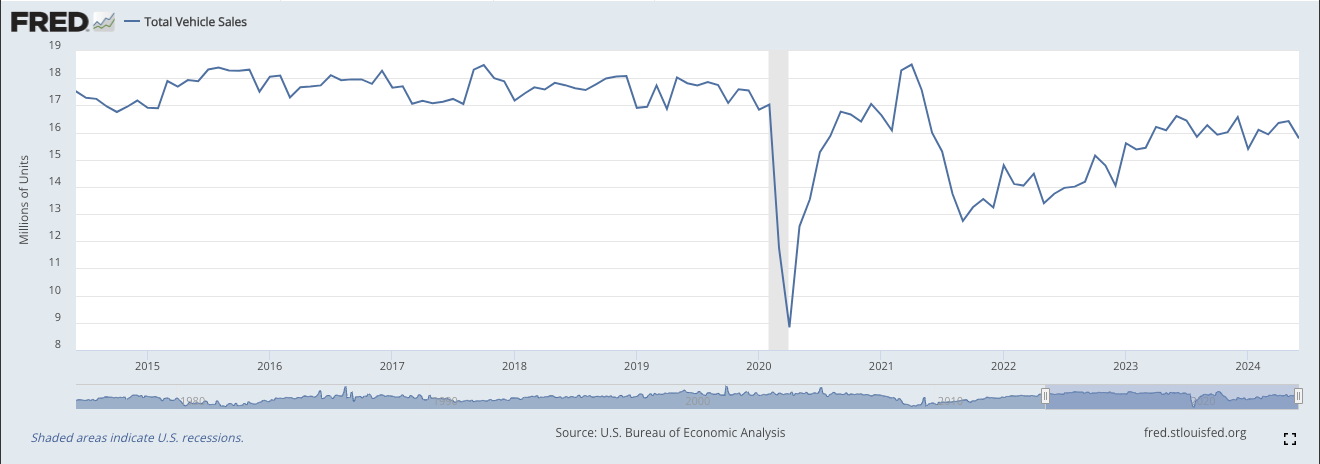

One beneficiary, according to some Wall Street analysts, could be homebuilders (some of the biggest – which are not recommendations, incidentally – are DR Horton (NYSE: $DHI), Lennar (NYSE: $LEN), and Pulte (NYSE: $PHM). It may also boost car sales, which have yet to regain pre-COVID levels.

And lower rates can’t come soon enough for some companies. Corporate debt has an average tenure of eight years in the US, and a surprising share of companies are struggling to pay just their interest expense.

Although the stat Herb cites below references 1,000 of the largest listed companies, most of those, by number, are going to be small caps. This is one reason small caps haven’t performed well against large caps of late: More debt, and more debt at (high) variable rates.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.