When Good Investors Go Bad

Neil Woodford was on top of the world.

“Britain’s Warren Buffett,” as he was called, had beaten the market for 25 years while at large money manager Invesco. So in May of 2014, he decided to go it alone by founding Woodford Investment Management.

If you’re an investor, what could be smarter than parking money with someone who’d beaten the market for a quarter-century?

Neil’s new fund thumped the UK FTSE index its first year – 18% versus just 2% – and grew to £10 billion.

Then Woodford, known for collecting mansions and supercars, but not for modesty, began to expand into small, illiquid companies not traded on exchanges.

Private market investing worked well for Warren Buffett, but less so for Neil Woodford.

When Neil’s investments started to struggle, concerned investors tried to withdraw – only to find there wasn’t enough money to meet demand. Woodford’s fund collapsed, resulting in big losses for most of its 300,000 investors.

Though the fund imploded in 2019, the drama is still ongoing with a High Court judge approving a compensation plan for burned investors in February 2024 and the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority in April 2024 concluding a review by declaring that Woodford had a “defective understanding” of illiquidity risks. The Woodford implosion has been the subject of at least one book, and the regulatory mess is not done yet, either.

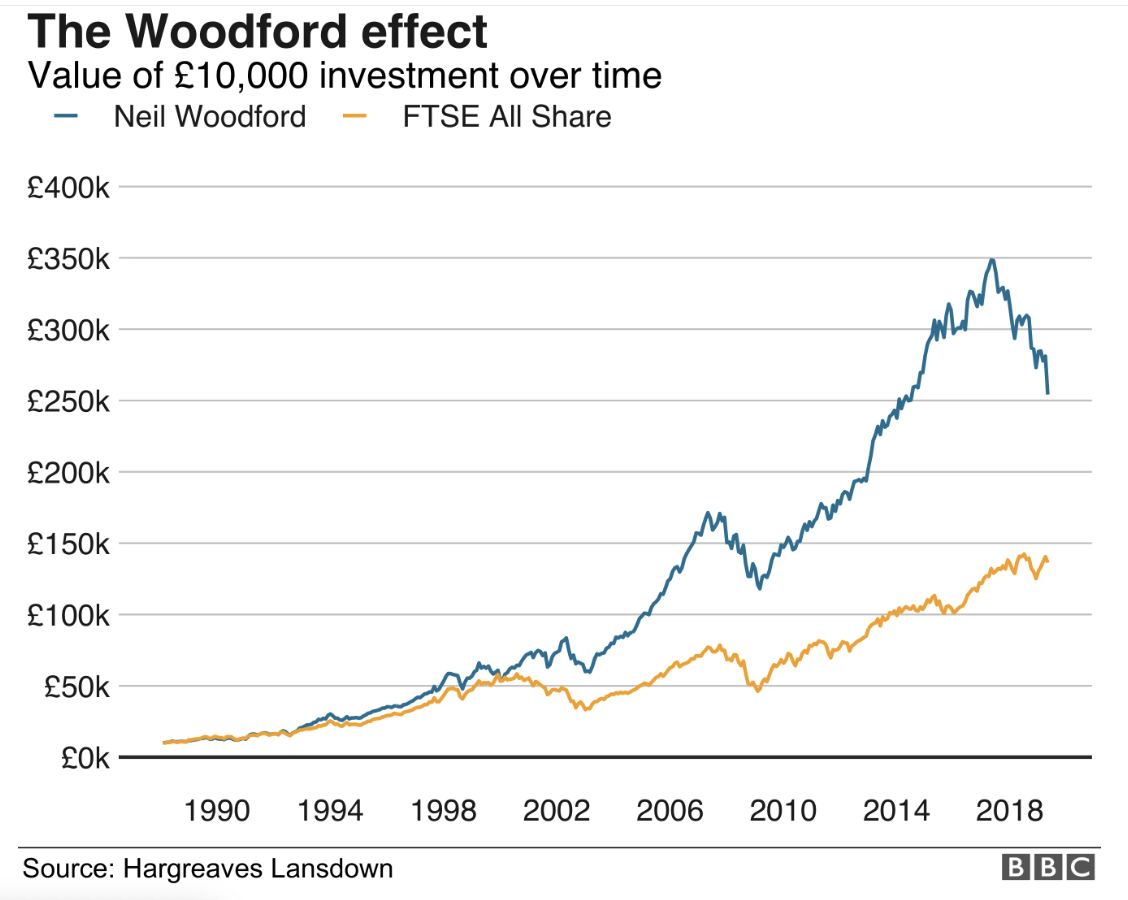

When eyeballing the BBC graphic below, keep in mind that Woodford, who is now a financial commentator, started his own shop in 2014, and presumably the money rolled in over the following few years – i.e., at prices at best equal to and most likely a lot higher than where the fund eventually settled.

To be fair, it was a chain reaction of worrisome performance leading to a liquidity crisis that did the Woodford fund in, versus solely poor performance.

But sometimes in investing, things go a certain way until they don’t.

From Midas Touch to Lead Touch (to Billionaire)

Bill Miller would understand.

The Legg Mason star beat the market 15 years in a row: every single year from 1991 to 2005.

With that kind of consistency, betting on Bill Miller would seem as obvious as betting on Neil Woodford.

And many did bet: Bill managed $77 billion for Legg Mason at his peak.

A few years later, Bill cratered his fund’s value by ⅔ thanks to high-conviction bets on financial stocks like Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, AIG, and Freddie Mac, which melted down in the Global Financial Crisis. His fund was last among the 840 funds in its category.

Even after the crisis passed, Bill’s performance was so hit-or-miss that Legg Mason, the Baltimore firm Bill almost single handedly put on the map, dumped him.

But unlike Neil Woodford’s, Bill Miller’s story has a happy ending: Bill clawed his way back with his own firm, Miller Value Partners, which has a hedge fund and mutual funds run by Bill and his sons. Bill’s Miller Opportunity Trust fund is a top-rated fund by Morningstar, beating the market most years. Bill even bought Bitcoin for his hedge fund in 2014 and is enjoying great returns from it.

So Bill came back, even if with a smaller fund. In fact, he’s a billionaire now.

Do All Investing Styles “Go Bad” Sometimes?

A 2008 article about Miller’s fall from Business Insider (introducing a Wall Street Journal interview) has an insightful assessment:

“… it’s hard not to come to the following conclusion: No strategy works in all markets, no strategy works forever, and no strategy can prevent the eventual onslaught of mean-regression.”

This Bill Miller article from Money mentions that for a value strategy, investors really need to be willing to park their money for a good 10 to 20 years.

I love the brutality of that statement.

It’s nothing we want to hear.

In a recent piece, I explained slot machine payout algorithms. Pretend a slot machine is set to pay out 90% of its intake, which is roughly typical. It would absolutely not pay out 90% over short time periods. Slot machines “save up” and pay out occasional huge jackpots – say, $800,000 after taking in $1,000,000. (The other $200,000 in payments along the way are to keep people playing.)

In other words, slot machine returns are very unevenly distributed.

What about investment returns?

If you’re a frequent BBAE Blog reader, you’ve heard me talk about ASU Professor Hank Bessembinder’s findings that since 1926, just 4% of US stocks have been responsible for all the gains, and that 60% of stocks lose money. And you may also remember that if you removed the best 1.2% of S&P 500 trading periods over the past 20 years, your returns would be 93% lower.

Concentrated-ness cuts both ways: If you’d missed the worst 1.9% of S&P 500 days over the past 20 years, your returns would be nearly 2,500% higher.

With returns-moving forces so concentrated in investing, it’s not a stretch to assume that it’s possible for entire investing styles to be prone to the occasional long-tail blow-up.

Are there “hundred-year floods” in certain investing styles?

What if some investable assets have loss patterns that are similarly unevenly distributed?

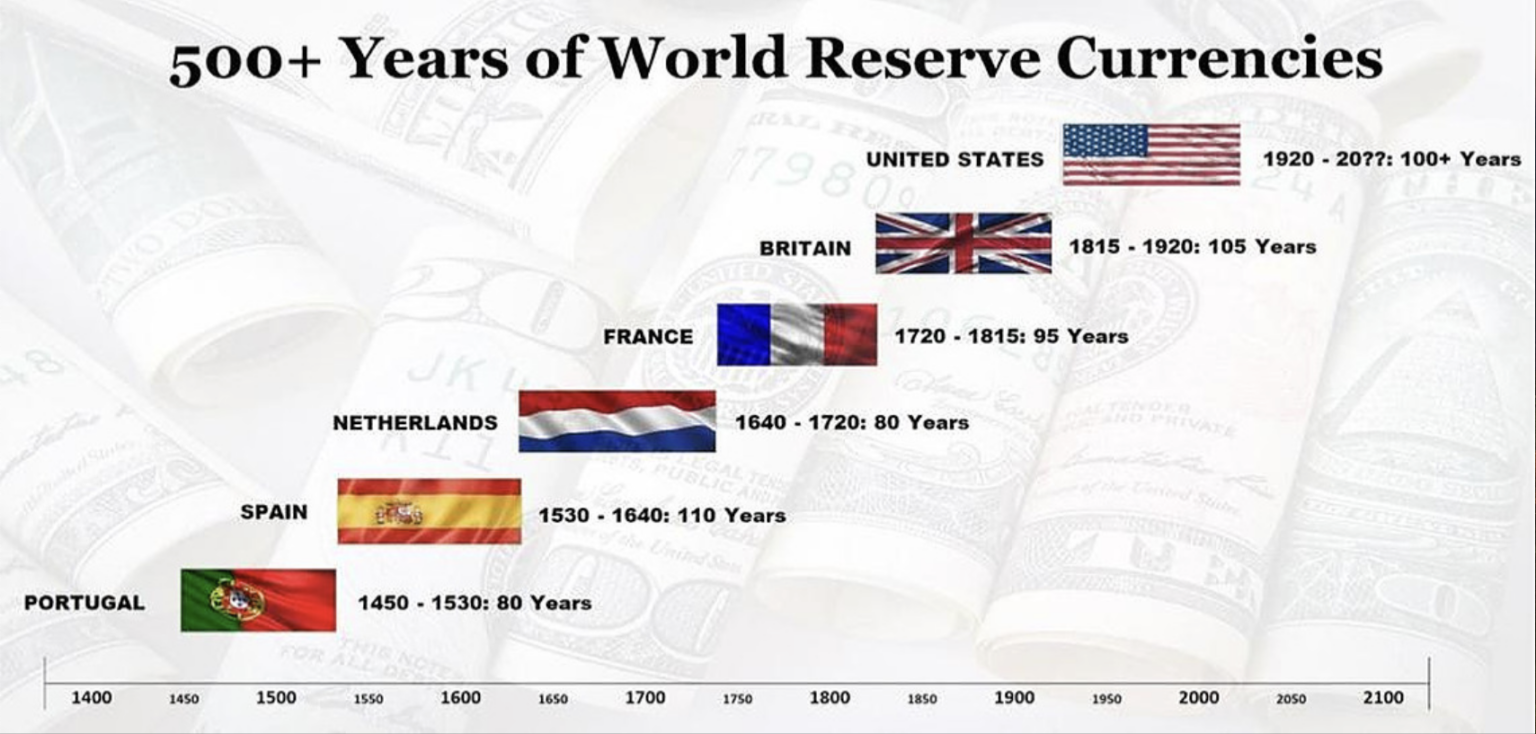

Currency is less of an investable asset for most individual investors (and wisely so), but thus far, world reserve currencies have – according to this gold website, so consider the motivation – lasted 94 years on average, with the US dollar having lasted 99 years.

A graphic posted by CryptoMarkets on Reddit (also consider the motivation) is somewhat more generous, but broadly to the same effect:

The US dollar ismore than a reserve currency. It’s technically a vehicle currency, too, meaning it’s the chosen currency for global transitions (“reserve” relates more to storage), but plenty of doomsayers have long been decrying the dollar’s downfall. They’ve been dead wrong so far – in fact, it strengthened post-2009, right when the doomsayers insisted it would crater – but will they one day be right?

And if so, will they really be right? Or will they just be stopped-clock ideologues who finally called the correct time by accident?

These questions don’t have clear answers. Sitting comfortably with such ambiguity is the essence of investing.

Most reasonably informed investors can grasp intellectually that investing has ups and downs. But studies show that even with that knowledge, it’s hard for them to act (or refrain from acting, when that’s best) on it.

In day trading, ups and downs are confined to single days – a short reinforcement cycle. But according to research, day trading doesn’t work out for around 90% of those who try it.

If humans keep day trading even though the payoff distribution is observably bad and materializes quickly, how can we process the notion that an investing style or manager is good, say, 15 out of 16 or 24 out of 25 years?

I don’t think we can.

The rearview mirror can deceive us. It was a good decision to invest with Neil Woodford in 2019, and it was a good decision to invest with Bill Miller in 2006.

It’s just that in a stochastic social science, good decisions don’t always pay off.

MarketGrader has payed off so far

At BBAE, we know that no investor can read the tea leaves all the time – and ditto for no investing style winning all the time. If so, everyone would use it to the point that it would cease winning, much like how when a new line opens up at Costco and everybody rushes in until that line becomes roughly equal to the others.

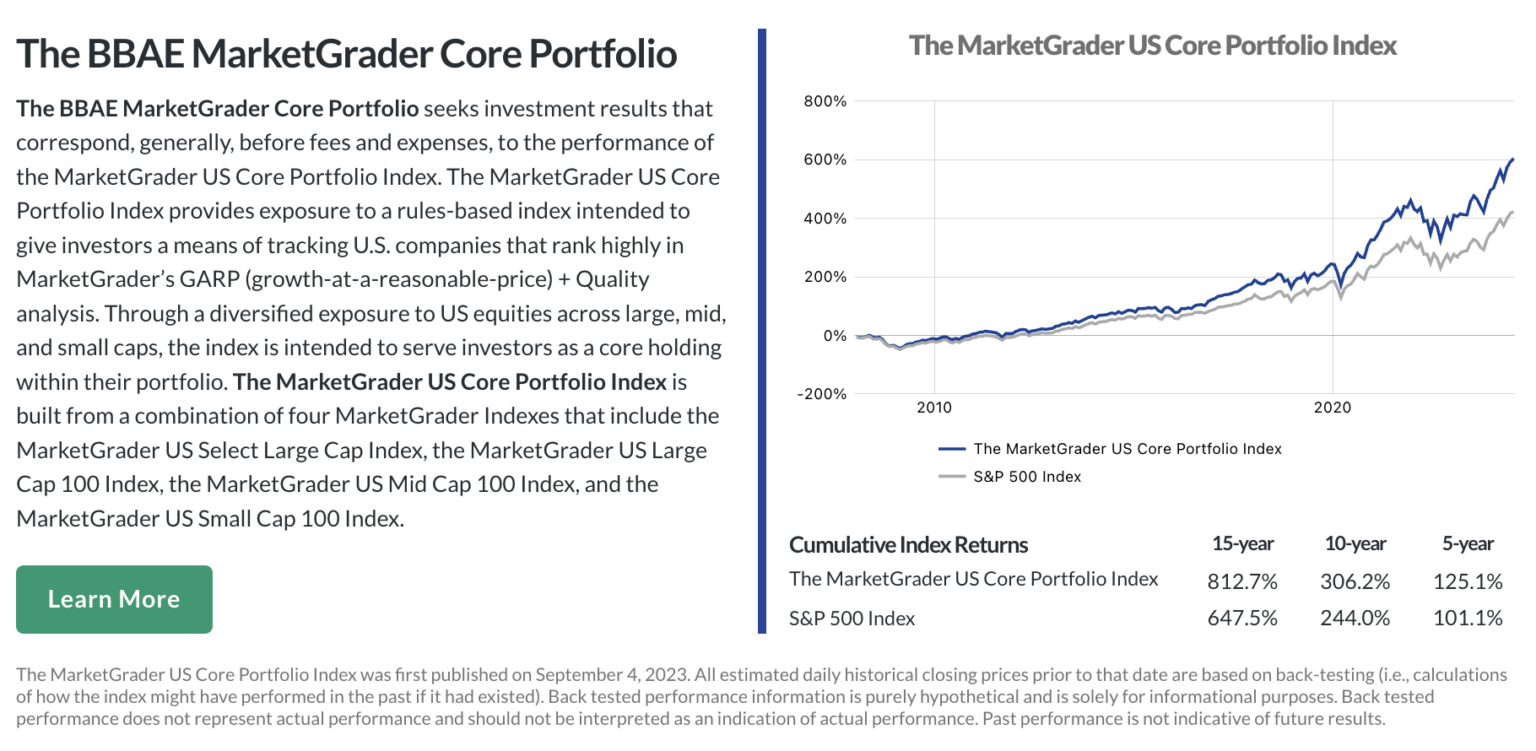

While we can’t solve all of social science’s mysteries, we can bring you investing options that diversify across factors and styles. We’ve brought you MarketGrader.

MarketGrader is a factor-based investing platform that uses 24 factors – nearly all fundamental, and most well-evidenced in academic research – to identify the market’s best (and worst) stocks. In fact, it ranks them.

I can’t give away MarketGrader’s secret sauce (because I don’t know it, though I know Carlos Diez, its founder, well), but for example, MarketGrader’s algorithm looks for growth at a reasonable price (GARP) via metrics that would be considered “value,” like price-to-book, metrics that might be considered “quality,” like ROE or other measures of operational wellness, and measures that might indicate growth or momentum – in fact, price momentum is one input.

The end result is a model that’s designed to be robust to market conditions, aiming to lessen blow-up risk while increasing the odds of superior risk-adjusted performance across different market periods.

And the end result is a history of delivering benchmark-beating results: Over MarketGrader’s history, 47 out of their 52 indexes (more than 90%) have beaten their benchmarks.

We proudly offer three exclusive-to-BBAE MarketGrader portfolios at BBAE and – guess what? – not only did they excel in backtests, which were conducted prior to their adoption, but they’ve all three beaten their benchmarks in live results during their year-plus deployment at BBAE.

You can check out the three BBAE MarketGrader managed account products here, noting they have minimums of only $2,000, versus the $50,000 and up you might find elsewhere.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.