The basic premise of investing in emerging markets is that they’re risky but offer the potential for huge growth.

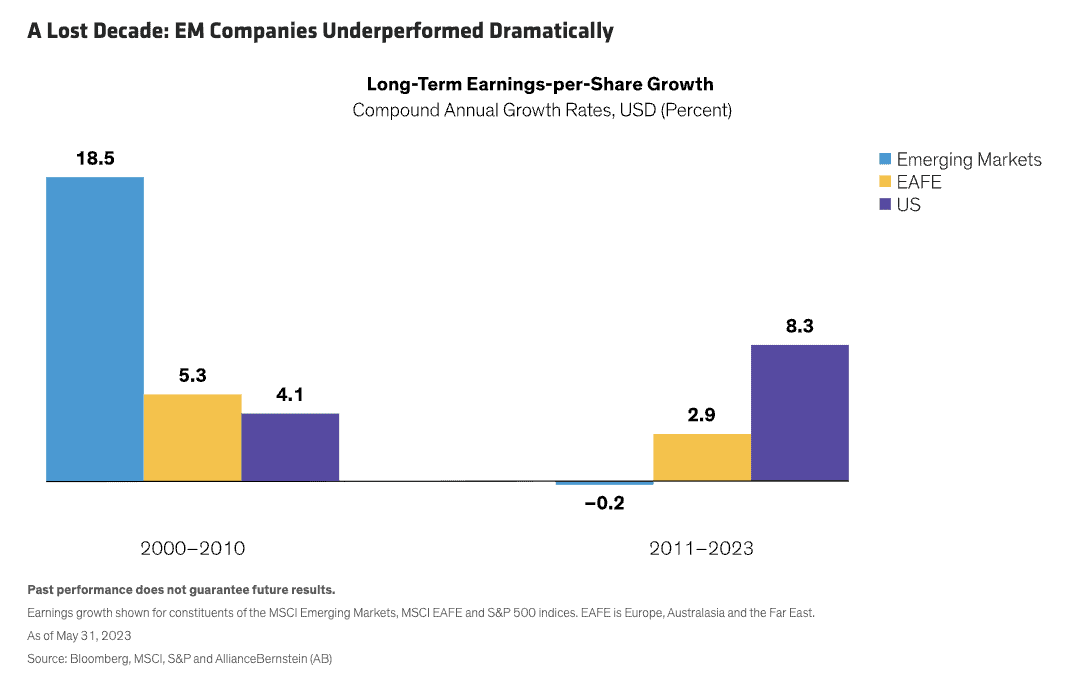

There’s evidence to back this up: as AllianceBernstein notes, 2001-2010 was the decade of emerging markets – they delivered a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 18.5% annually.

This was enough to make emerging markets a thing. An asset class.

Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel in 2015 even suggested a 25% portfolio allocation to emerging markets.

That advice (I’ve met Jeremy and feel he generally gives excellent advice) would not have served you well: as AllianceBernstein also notes, emerging markets have returned, on a CAGR basis, -0.2% annually since 2011.

Yikes.

But old memories die hard.

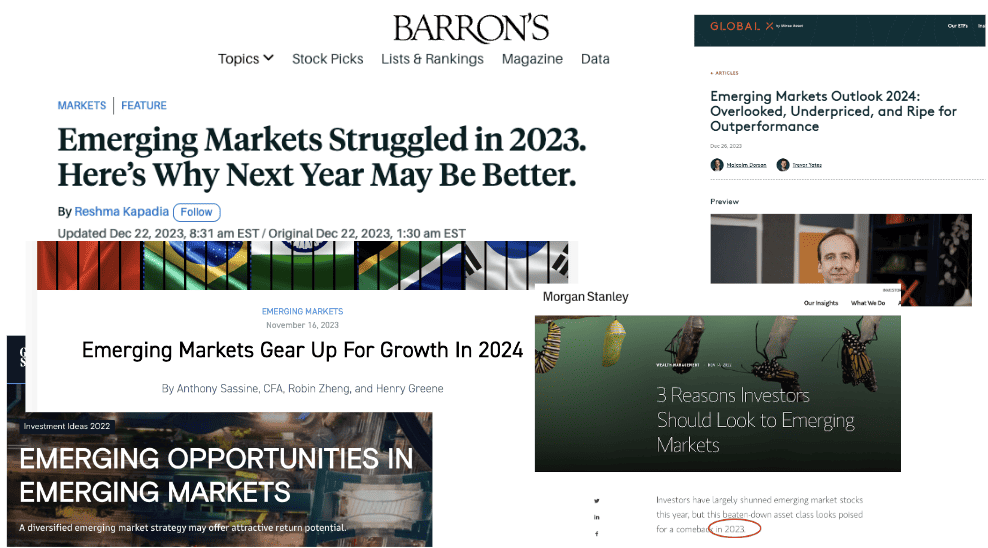

If you spend a little time reading the headlines, you’ll notice a chorus of voices every year – whether it’s 2016 or 2022 or 2023 or probably any other year – claiming that things are about to change for EMs. An emerging market turnaround is just around the corner.

Except that it hasn’t happened.

I’m not one to cast stones: I allocated a fair chunk of my own portfolio to emerging markets years ago and bear some scars.

Two reasons why emerging markets are down

Why have emerging markets taken such a beating?

- One reason is China’s slowdown. After joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, China’s GDP growth went on a tear – from 8.3% in 2001 to 14.2% annually in 2007. It wasn’t until 2016 that growth dipped below 7%, at least officially.

In several of those years, China contributed more than half of the entire world’s GDP growth.

China’s slowing doesn’t explain everything, but it explains some: the Chinese stock market has been dead money for the past decade (incidentally, China was phased into emerging market ETFs – first came Hong Kong shares in 1996, and then true domestic “A” shares in 2018, with yearly weights increasing).

- A bigger reason is the US dollar. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the US dollar is involved in 90% of foreign exchange transactions. And according to the Financial Stability Board, more than 80% of emerging market debt is denominated in US dollars.

If you’re an emerging market country selling your exports in US dollars, a more valuable dollar slows demand by making your stuff more expensive. That’s a particular bummer when you have debt payments to make in US dollars, too, as those get a lot harder to make when your local currency loses potency relative to the dollar.

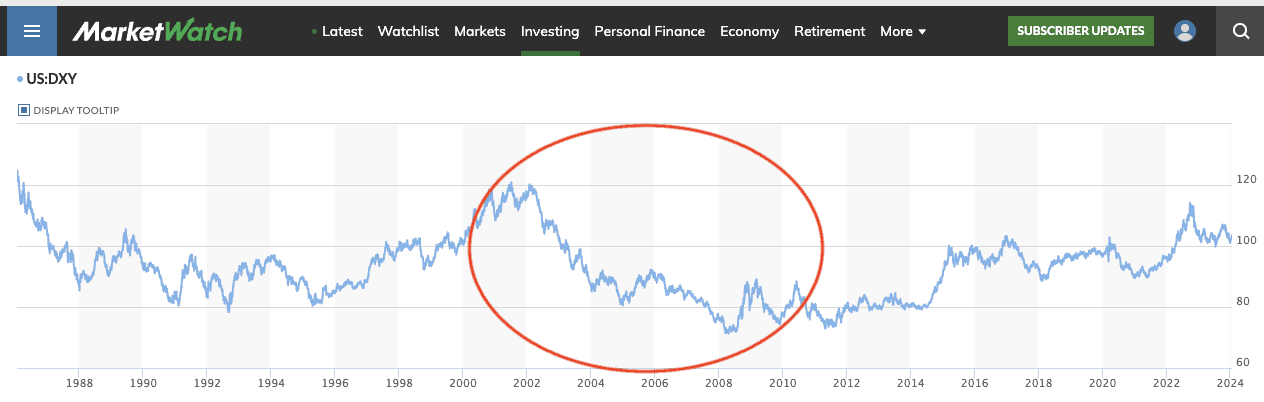

As you can see from the chart below, the US dollar declined meaningfully from 2001 to 2010, giving emerging markets a huge tailwind.

Reasons why emerging markets may go back up

- The US dollar may cheapen. I have to be careful saying this because, speaking of “chorus,” there is absolutely a chorus of voices calling for the imminent demise of the dollar – practically all the time.

Some members – not all, but many of the most vocal ones – of this chorus hail from the far right and believe that the US’s deficit spending and money printing will bring the dollar down. These voices were especially loud during the US’s response to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. But they were dead wrong, too – the dollar strengthened massively as the rest of the world decided that during a time of crisis, the US was the safest place to be, quantitative easing and all.

Source: The Independent

It’s possible that this “dollar demise” chorus is just flat-out wrong. They certainly have been so far.

But I don’t write them off. The other possibility, as I’ve said before, is that they’re “right” about all this deficit spending leading to trouble, but it’s the sort of thing that you can only call with an accuracy of +/- 70 years or 100 years, or some long time period. This might be loosely akin to warning a young smoker that he’s risking cancer.

- Emerging markets are emerging and their stock markets – currently punching below their weights – will rise to be more in keeping with these countries’ GDPs. Credibility has been the limiting factor here. The US, for all its warts, has the most credible, reliable, and battle-tested financial system in the world – and the most robust capital market. (So good, in fact, that the best companies and often entrepreneurs gravitate toward the US, or at least its exchanges.) To give a ridiculously arrogant analogy – which, as an American I’m expected to do – US markets are the Major League Baseball equivalent of the financial world. The reason players play in the minor leagues is because they can’t play in the Major League; if they get good enough to move up, they do. Global markets are not quite like that – in fact, they’re definitely not like that – but there’s at least a bit of that dynamic between emerging markets and the US.

But this pro-EM argument, in its purest form, is one made by Global X analyst Malcom Dorson: emerging markets make up 80% of global GDP growth, but only 11.7% of global market cap.

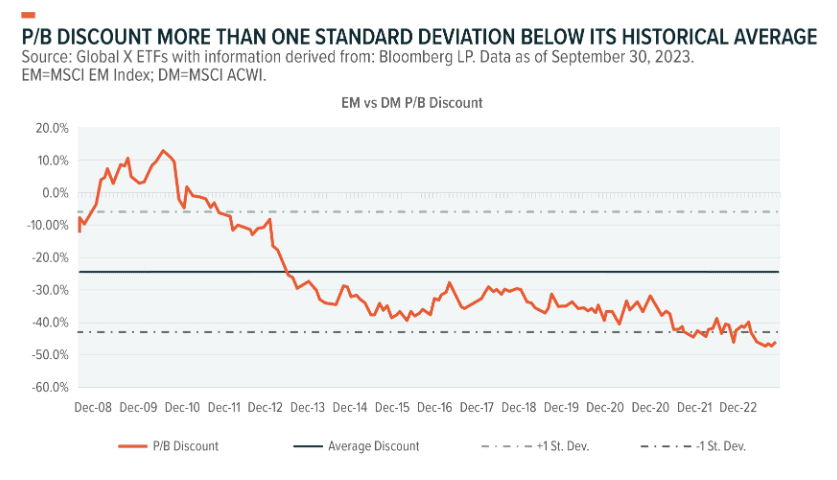

- Emerging markets are just really cheap. Cheap things can always get even cheaper – mean reversion is never guaranteed. But, again from Global X, on a price-to-book basis, emerging market equities are trading especially cheaply relative to developed market ones. This counts for something.

Blogger Nick Maggiulli of Ritholtz Asset Management asks a fair (if inadvertently smug-sounding) question: since US stocks have done so well, does an investor (from anywhere in the world) need to buy anything other than US stocks?

Nick’s conclusion: you can find time periods that show US investing to be better, and you can find time periods that show investing outside the US to be better. No definitive answer.

Investing, after all, is a relatively new social science, and the subjects of study are constantly evolving – especially so of emerging markets, to which I think Nick’s conclusion applies well.

You could make a good case for emerging markets. You could make a good case against them (or even that lumping them into a single bucket misses too much nuance to justify the convenience).

As for me? I can’t predict if or when they’ll rise from the ashes, but I’m not selling my emerging market investments.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.